By ELIZABETH LOLARGA

THE lessons that nonagenarian Jean McGarvin de Vera preaches to this day from her kitchen in Baguio City are simple:

· Cooking is quotidian, use your common sense.

· Cooking is nurturing, more than just feeding.

· Cooking is compassion.

· Cooking is an art.

This lady’s precious, colorful life is captured by Adelaida Lim and de Vera’s daughter Leonisa Bautista in A Matter of Taste: The Culinary Memoirs of Jean McGarvin de Vera, the maiden publication of Mt. Cloud Bookshop. The spiral-bound book is also a chockfull of recipes, some of them lusciously photographed by Philip Bautista, Emerson Bimuyag and Donald Rentiquiano. There are charming black and white vignette illustrations by Solana Perez.

Formerly known as Sing Wei (it means “good heart” in Chinese), de Vera survived the communist takeover of China (she came from a land-owning family), hastily fleeing to the Philippines with gold to pay for passage and arriving in Manila as refugees with her husband Philip and three children. They started afresh in provincial Pangasinan where she felt restless, having been brought up amidst the comforts of worldly Shanghai where “everything and anything was available: caviar from the Russians; curry and chutney from the British/Indians; wine and cheese from the French.”

In the adopted country, de Vera already had this “sophisticated and cosmopolitan palate,” but in provincial town of Mangaldan, Pangasinan, where the family resettled, she had to cook with firewood, scrub pots until her hands were blackened with soot, fetch water from an artesian well, haul buckets of water from the well to the house and learn the Ilocano way of preparing simple dishes like dinengdeng.

In the adopted country, de Vera already had this “sophisticated and cosmopolitan palate,” but in provincial town of Mangaldan, Pangasinan, where the family resettled, she had to cook with firewood, scrub pots until her hands were blackened with soot, fetch water from an artesian well, haul buckets of water from the well to the house and learn the Ilocano way of preparing simple dishes like dinengdeng.

The unsinkable de Vera earned a reputation as a good cook. Parish priests from all over the province invited her to cook adobo, mechado, kilawin, dinuguan, igado, menudo and chop suey in big quantities during fiesta. She said, “I learned, I practiced, I improved the recipe. That is my secret technique—learn, practice, perfect…I am by nature, very nosey. Curious. I want to know how everything works.”

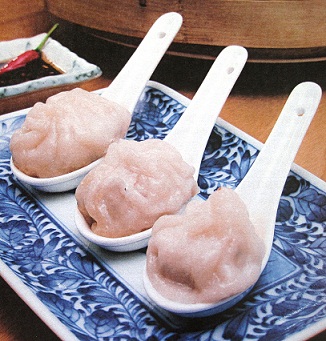

This Confucian ethic saw her through hard times after the war and widowhood when she became a resourceful entrepreneur in order to raise and educate her young children. She made asado and curry siopao while a son helped her by selling them at the town’s gambling den. This was her fallback and surefire business wherever, whenever she found herself faced with financial challenges.

Apart from siopao, de Vera also produced packs of frozen siomai, wontons and Shanghai lumpia with her kids assisting her in the packing. She worked as a cook at the St. Joseph’s College canteen where daughter Leonisa was attending college. She later opened a canteen for computer school students until even office workers in Makati started patronizing her hole-in the-wall joint.

These feats were unsurprising because as a 14-year-old girl in Shanghai, she already cooked a banquet made up of 10 or more dishes for her mother’s birthday. She recalled, “I cooked for three tables of ten people each.” A Chinese lauriat has several parts: a cold plate of savory tidbits; a series of hot dishes that are served one at a time; four whole entrees served on the table at the same time; and finally, steamed rice or fried rice in a covered bowl.

An itemization of what she prepared for her mother is hand-drawn by Perez with peonies decorating the long, mouth-watering menu: Tea-leaf Eggs, Lap Chong, Head Cheese, Pickled Icicle Radish, White Cut Chicken and Wine, first course; Shrimp Toast, Kidney with Bamboo Shoots, Cuttle Fish Flowers with Red-in-Snow and Beef Tenderloin with Celery, second course; Four Happiness Pork Belly, Whole Poached Chicken, Friend Fish with Sweet and Sour Sauce, Steamed Delight, Hand-rolled Noodles with Shiitake Mushrooms, entrees; Almond Cream Soup with Sticky Rice Balls, sweet finale.

An itemization of what she prepared for her mother is hand-drawn by Perez with peonies decorating the long, mouth-watering menu: Tea-leaf Eggs, Lap Chong, Head Cheese, Pickled Icicle Radish, White Cut Chicken and Wine, first course; Shrimp Toast, Kidney with Bamboo Shoots, Cuttle Fish Flowers with Red-in-Snow and Beef Tenderloin with Celery, second course; Four Happiness Pork Belly, Whole Poached Chicken, Friend Fish with Sweet and Sour Sauce, Steamed Delight, Hand-rolled Noodles with Shiitake Mushrooms, entrees; Almond Cream Soup with Sticky Rice Balls, sweet finale.

The authors observed admiringly, “Such a feat requires virtuosity. One needs to be methodical and calm.” And to think that her American father forbade her from cooking, fearing that she would get hurt in the kitchen’s hustle and bustle.

The authors and publisher must be congratulated for “rescuing”, documenting and preserving de Vera’s unique story, voice and priceless recipes. They have done the Baguio community and the nation a great service for doing so.

Common sense and fortitude saw de Vera through what would have been for lesser persons a difficult life. In sharing through the book, she adds a culinary and biographical link to the ever-evolving cache of Baguio and Chinese-Filipino stories.

A Matter of Taste (available at Mt. Cloud Bookshop) has the flavor of a fried dish that the book’s subject recommends when planning a lauriat: “Delicate, without bones.”

Wishes for a long life to Jean McGarvin de Vera!