By KIERSNERR GERWIN TACADENA

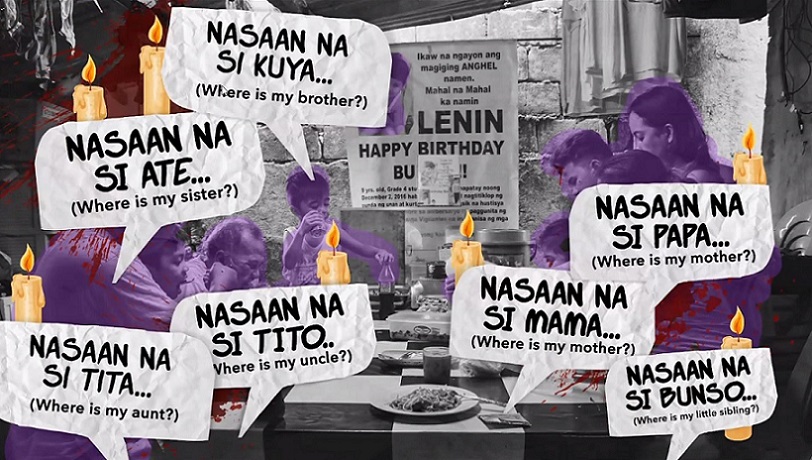

MACKY Lumangtad, 12, would always hang out with his friends in the famous Freedom Park of Tagum City to play computer games at night. On April 21, 2011, a man known as “Wacky” who also frequented the plaza approached Lumangtad. The next day, his body was found in a vacant lot bearing a gunshot in the head.

Hours after Lumangtad’s body was discovered, the dead body of another child, 9-year old Kokey Lagulos, was found bearing 22 stab wounds.

Lumangtad and Lagulos have nothing in common except for the rumor that they belong to a group of children who carried out several thefts in the city.

“In Tagum City, those types of rumors are enough to get you killed,” Phelim Kine, deputy director of Human Rights Watch (HRW) Asia, said.

“In Tagum City, those types of rumors are enough to get you killed,” Phelim Kine, deputy director of Human Rights Watch (HRW) Asia, said.

HRW is an international human rights advocacy group that conducts investigations on human rights violations.

HRW released Wednesday a 71-page report, “’One Shot to the Head’:Death Squad Killings in Tagum City, Philippines,” detailing what is said was the connection of hundreds of killings in Tagum City to former City Mayor Rey Uy’s death squad and the police.

According to the report, the death squad targeted alleged petty criminals, drug dealers and street children which Uy called as “weeds” and “undesirables” of the Tagum society.

“It is an apparent and perverse crime control measure by this former mayor, so called ‘anti-crime initiative,’” Kine said.

Uy, in an interview with Interaksyon Online News, refuted the HRW report, saying his political rivals, drug lords and protectors of criminal groups want to destroy his reputation to prevent his political comeback in 2016.

The HRW report said, however, Uy patterned the formation of the squad after the task force in Davao City by its mayor, Rodrigo Duterte.

Uy organized at least 14 hit men and accomplices when he first sat as mayor in 1998. Many of these men were on the city government payroll under the Civil Security Unit (CSU), a bureau tasked with providing security, Kine said.

“As members of the Civil Security Unit, the death squad got government-supplied hand guns, motorcycles, all the equipment they needed to perpetrate these killings,” Kine said.

From 2007 to 2013, HRW documented 298 killings allegedly committed by the death squad, 12 of which were verified by HRW through accounts and affidavits.

Kine said HRW managed to interview and include in the report accounts from four former death squad members, eyewitnesses and families of the victims.

He said police have a strong connection to the killings based on the accounts the people HRW interviewed, including a police investigator who wished to remain anonymous.

In the video provided by HRW, the police investigator said they could not do anything when the death squad is involved in a case.

“You cannot disobey the mayor’s orders. We could not arrest them, so we just kept quiet. But we knew what they were doing,” the police officer said.

Romnick Minta, former death squad member, said the police knew beforehand the execution of the killings. He said the orders would come directly from Uy.

“We were ordered to get two or three head every week,” he said.

Minta said the mayor would pay them P5,000 for every killing. This is exclusive of the P10, 000 a month salary he got as a member of the CSU.

“They said they wanted to change Tagum, so that bad elements would think twice in coming (to the city) because they would end up dead,” Minta said.

Kine said that the death squad members in 2005 began to carry out “guns-for-hire” operations.

“They would target not the usual undesirables. The victims would include individuals like business people, a journalist, a judge,” he said.

HRW said killings continued even after Uy left his post although not as rampant.

Last month, it was media reported that the National Bureau of Investigation had recommended the prosecution of four security guards employed by the Tagum City government for their alleged role in the abduction, torture and murder of two teenage boys in February 2014.

The current Tagum City mayor, Allan Rellon was quoted in media as saying he was “bewildered” by the allegations because, “As a local chief executive, I abhor any form of summary killing.”

Kine said the evidence of these extrajudicial killings calls for an immediate government action:

“It is unacceptable that impunity remains so widespread. It reflects the central government’s very passive attitude toward the activities of anti-crime politicians,” he said.

HRW called on the government to direct the Office of the Ombudsman and the NBI to investigate the summary killings in the city and prosecute all those involved in the death squad activity.

Kine said that none of the cases recorded since 2007 has been prosecuted.

“The lack of action speaks volumes for the systemic failure from the local level to the top in terms of bringing the perpetrators into justice. There’s not a lot to be optimistic about,” he said.

Kine said HRW gave copies of the report in advance to several government institutions and individuals, including Rellon, Uy, the Philippine National Police, Department of Justice and Department of Local And Interior Government.

Commission on Human Rights (CHR) Commissioner Jose Manuel Mamauag said his agency will conduct its own investigation on the reported cases through its regional office in Davao.

The CHR will take up the recommendations of the HRW in its next meeting.

(The author is a University of the Philippines student writing for VERA Files as part of his internship.)