By VERA FILES

(First of three parts)

THE Judicial and Bar Council is now the focus of national attention as it begins the process of recommending a replacement for ousted Supreme Court Chief Justice Renato Corona. The process, if done right, is expected to help restore public confidence in the High Tribunal.

Yet many in the legal profession, the judiciary and civil society say the JBC needs reforming, because it is partly responsible for the problems in the judiciary. These problems are exemplified by the rise and fall of Corona, a “midnight appointee” who was eventually impeached and convicted for violating the Constitution and betraying public trust.

The 1987 Constitution vests in the JBC the responsibility of nominating qualified candidates to the judiciary, including the Chief Justice, to the appointing power, the President. It was supposed to remove politics from the appointment processes of the past. From 1972 to 1986, judicial appointments rested solely in the hands of then President Ferdinand Marcos. In the pre-martial law era, appointments to the judiciary made by the President passed through the Commission on Appointments, a body composed of members of the Senate and the House of Representatives.

But several lawyers, judges and members of civil society interviewed over a four-month research questioned the independence of the JBC, whose members are often alter egos of the President appointed to supposedly make sure his choices end up in the council’s list. Nominees, meanwhile, have resorted to lobbying with not only Malacanang but with the JBC to get into the coveted shortlist, relying on backers that include politicians, presidential friends and relatives, and even religious leaders, including bishops.

JBC composition

The JBC is composed of eight members, four of them ex officio, which means they sit by reason of their office. These are the Chief Justice as ex officio chairman, the Secretary of Justice, and one representative each from both houses of Congress, traditionally the chairperson of the Justice and Human Rights Committee in the Senate and the Justice Committee in the House.

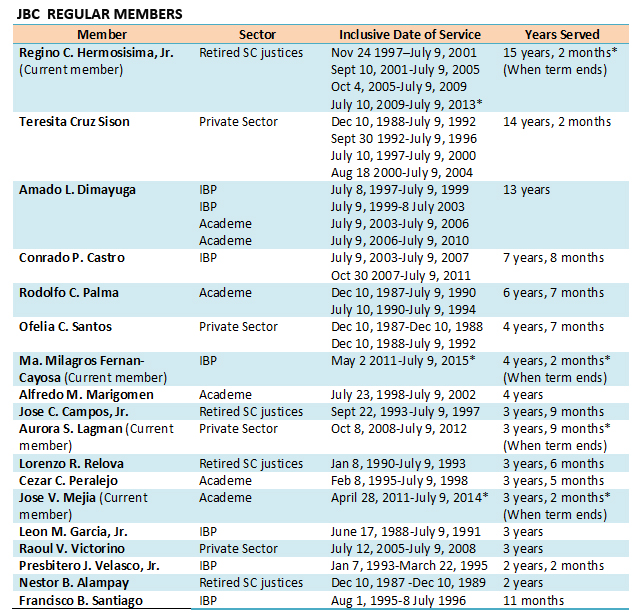

The other four are regular members appointed by the President and confirmed by the Commission on Appointments. They represent the Integrated Bar of the Philippines, the law schools, retired justices of the Supreme Court and the private sector.

Over the years, the interpretation of the constitutional provision on Congress’ representation in the JBC has changed. The Constitution created a seven-member council and gave Congress one seat. For more than a decade, representatives of the Senate and the House of Representatives alternately represented Congress in the council and shared one vote. But the setup changed in 2001 when they were given one vote each.

The concession given to Congress, critics point out, has made the JBC more politicized as the legislative branch ended up having a bigger say than the executive and judicial branches, each of which continues to have only one vote.

Sources say the two members of Congress and the justice secretary have been known to vote according to the President’s preferences on numerous occasions, with the Corona experience just one of many examples.

In September 2001 when Corona was nominated associate justice, Sen. Francis Pangilinan and then Taguig Rep. Alan Peter Cayetano represented Congress in the JBC. During the deliberations in 2001, these two, along with the other JBC members, apparently ignored the warnings of Jose Ma. Basa III who had gone to the JBC and accused Corona of “condoning the unfair and unlawful actions of his wife” in the Basa-Guidote family land dispute. Corona ranked first in the JBC shortlist in 2002, and was appointed April 9, 2002.

In his centennial lecture at the University of the Philippines College of Law last year, retired Chief Justice Reynato Puno singled out the three ex officio members as “carriers of the virus” of “partisan politics,” who, he said, could turn into the “swing votes” in determining who makes it to the shortlist to be submitted to Malacanang.

Regular members

Some lawyers also question whether the regular members exercise independence and whether they truly represent their sectors, when it is the President who appoints them.

“There is no genuine representation from the different sectors. It’s the fault also of the stakeholders. They did not organize. They failed to insist that the JBC representative come from their ranks,” one source said.

Rolando Inting, executive director for administration of the IBP, cites the IBP as example.

In the initial years, whoever was IBP president was automatically its representative to the JBC. Later, the President appointed the representative endorsed by the IBP board.

In 1997, however, then President Fidel Ramos reversed the process when he appointed his personal choice, Amado Dimayuga, who did not have the prior recommendation of the IBP board. “(Dimayuga) was first appointed by Ramos without the prior conformity (of the IBP board). He got the conformity later,” Inting said

Only recently, under President Benigno Aquino III, was the IBP again able to nominate its own choice: Milagros Fernan-Cayosa.

But Aquino’s appointment of the current representative of academe to the JBC, lawyer Jose Mejia, has rankled people in and out of the court. Reportedly a classmate of Executive Secretary Paquito Ochoa, who helps vet nominees for the judiciary in behalf of Aquino, Mejia is not a law school professor, but a faculty member of the De La Salle University College of Business and Economics, teaching commercial law to business and economics undergraduates.

The Constitution provides a four-year term for regular members but imposes no limit to their reappointment. Retired SC Associate Justice and now JBC executive committee chairman Regino Hermosisima, for example, has been appointed four times as the representative of retired justices. He has been on the council for 14 years.

Regular members may also be reappointed in varying capacities. Dimayuga was first appointed as IBP representative and later as a representative of the academe. A dean emeritus of the University of Santo Tomas where he teaches civil law, Dimayuga logged 13 years in the JBC.

Sources said the desire to stay on in the JBC may affect the independence of regular members. “If JBC members want to be reappointed, they have to do the President’s bidding,” said a member of the judiciary.

Interestingly, an occasion when regular members demonstrated their so-called lack of independence also had to do with Corona. In 1998, as his term was drawing to a close, Ramos wanted the JBC to fill up the position vacated by SC Associate Justice Ricardo Francisco who had retired that February. Palace insiders said Ramos wanted to appoint Corona, his chief legal adviser, to the high tribunal despite the election ban on appointments.

A few days before the elections in early May, in an exchange of letters with then Chief Justice Andres Narvasa, Ramos insisted that the council convene and submit nominees for the vacancy.

When Narvasa refused to do so, the four regular JBC members, all Ramos appointees, attempted to convene the council and asked then Justice Secretary and ex-officio member Silvestre Bello III to preside over the meeting in the absence of the Chief Justice. But Bello, in a bid to avert a crisis, decided to phone Narvasa who prevailed upon the other JBC members not to nominate anyone.

The high tribunal subsequently issued an en banc resolution supporting Narvasa’s position to observe the restriction on the President’s power to appoint during that election period, even if the Constitution provides that vacancies in the High Court must be filled within 90 days after they occur. The SC further stated that the ban includes appointments to the judiciary and not just executive appointees.

Ironically, the Supreme Court reversed itself in 2010, paving the way for Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo to appoint Corona as Chief Justice during the election ban. By then, the High Court was already packed with her appointees, many of whom had breezed through the JBC, and had earned the scathing moniker the “Arroyo Court.”

Criteria for nomination

The JBC is empowered to accept and filter nominees for the posts of Chief Justice and the 14 associate justices of the Supreme Court, 69 justices of the Court of Appeals, 15 justices of the Sandiganbayan, nine justices of the Court of Tax Appeals and more than 2,200 judges in the regional trial courts and lower courts. It also nominates the Ombudsman and his or her deputies.

The Constitution requires appointees to be of proven competence, integrity, probity and independence. Candidates to the Supreme Court must also, at the minimum, be a natural-born citizen of the Philippines, at least 40 years of age, and must have been for 15 years or more a judge of a lower court or engaged in the practice of law in the country.

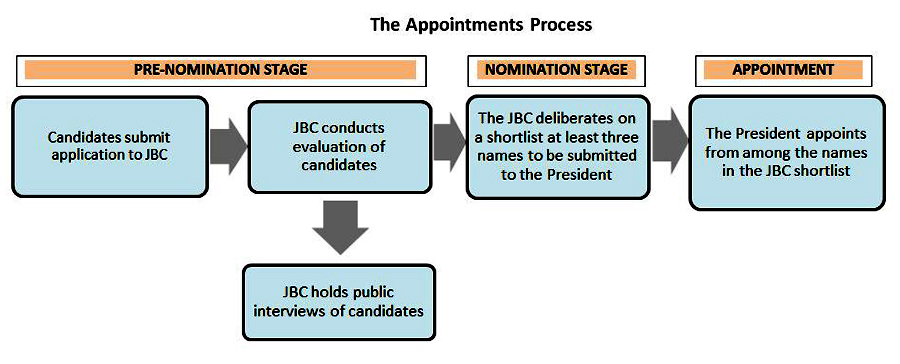

The whole process starts with the call for applications for vacancies posted in the JBC and the Supreme Court websites.

An applicant’s competence is weighed based on his or her education, experience, performance and other accomplishments like authorship of law books, treatises, articles and other legal writings, whether published or not; and leadership in professional, civic or other organizations. Completion of the prejudicature program of the Philippine Judicial Academy is required, but may be waived in places where there are not enough applicants.

The JBC enlists the National Bureau of Investigation to do background checks on applicants. But JBC Executive Officer Annaliza Ty-Capacite said the NBI does not always submit its findings on time. There have been instances when the applicant was already appointed but the NBI had yet to get back to the council with the outcome of its investigation.

Written opposition and even testimonies of oppositors at a hearing conducted for the purpose are entertained. Anonymous complaints, however, are not, unless there is probable cause that the accusations against the applicant are true.

In 2009, the council started to implement the Survey System on applicants to the appellate courts to supplement the NBI background check. Survey forms, formulated by the research institution Social Weather Stations, are given to the applicant’s colleagues to fill out. The results of the survey are given persuasive weight.

The council also makes sure that the applicant possesses none of the disqualifications for the position: no pending criminal or administrative cases in local or foreign courts, and no conviction in any criminal case or in an administrative case, where the penalty imposed is at least a fine of more than P10,000, unless he has been granted judicial clemency.

Bending the rules

The JBC, however, has in the past bended the rules to accommodate the President. In 2009, it voted to relax the rules on age limits for Supreme Court nominees. That rule stated: “The Council shall not consider for nomination non-career and career applicants who may no longer be able to serve the court for at least five years or for at least one and one-half years, respectively, before reaching the compulsory age of retirement,” which was 70.

The moved benefited Rodolfo Robles, a private practitioner and a friend of then President Arroyo who was being considered a candidate for associate justice. Robles was 65 years and four months old at the time, and would have served less than the required five years.

Robles made it to the shortlist submitted to the President, to the chagrin of civil society groups then monitoring Supreme Court appointments, but he was not appointed.

Meanwhile, ex officio member and Iloilo Rep. Niel Tupas once proposed to relax the JBC rules on qualifications for nomination and allow those who have been fined by up to P20,000 to be considered for appointment or promotion to the judiciary. He was roundly criticized by former Chief Justices Hilario Davide, Artemio Panganiban and Reynato Puno, and by the Supreme Courts Appointments Watch (SCAW), a judicial watchdog.

And the JBC has still to live down its mistake of nominating Chinese-born Gregory Ong to the vacancy in the Supreme Court in 2007. Ong actually got appointed by Arroyo who was, however, forced to withdraw his appointment the day after she announced it when civil society groups Kilosbayan Foundation and Bantay Katarungan raised the citizenship issue before the Supreme Court and eventually won the case. (Ong heads the Sandiganbayan’s Fourth Division which is trying the graft cases against Arroyo, including those stemming from the controversial $329 million national broadband network contract with China’s ZTE Corp.)

Shortlist

Based on the deliberation and evaluation, the JBC comes up with a shorter list of applicants to be interviewed. The dates of the interviews of candidates in the shorter list must be published in two newspapers of general circulation, and in both the Supreme Court and the JBC websites.

The council en banc, or any panel of members authorized by the council, then conducts a personal interview of candidates to observe their personality, demeanor, deportment and physical condition, and to assess applicants’ ability to express themselves, especially in the language of the law in court trials and proceedings and in their decisions or rulings.

A 2002 resolution mandated that interviews be made public, but cameras and tape recorders are not allowed inside the room. Television and radio coverage are also prohibited. Only the members of the JBC can ask questions of the candidate. In 2011, however, Vincent Lazatin of SCAW was allowed to broadcast in real time his observations of the public interviews of candidates for the position of Ombudsman using the social media network Twitter.

After the interviews are completed, the JBC meets in executive session for the final deliberation on the shortlist of candidates. Under its own rules promulgated in 2000, the council must give “due weight and regard” to the recommendees of the Supreme Court when the slot at stake is in the highest court of the land.

For the Supreme Court and lower appellate courts, a list of at least three nominees for every vacancy has to be transmitted to the President. Candidates are ranked according to the number of votes they garner in the shortlist sent to the Office of the President. In 2008, the JBC approved the open voting system, in which the tally sheets of the JBC members’ votes during their closed-door deliberations are to be released to the public. (Names of candidates to lower courts are not ranked.)

But, citing anecdotal evidence where the JBC had failed to muster a majority vote of all members and demonstrated inconsistencies in voting patterns, among others, the SCAW said the council’s selection process is hardly a filtering system for the best and the brightest.

According to SCAW, there had been cases where the JBC went through two rounds of voting because the first round failed to come up with at least three names that garnered the required majority vote of council members. A JBC member once admitted that the shortlist submitted to the President was expanded, including candidates not previously qualified, at the request of the appointing power.

In at least two instances in 2009, SCAW said the JBC twice “forced itself to come up with six names even if there were not six qualified candidates among the pool of applicants” for two vacant SC positions, just to satisfy the single search and shortlist process.

(To be continued)

(This series is adapted from VERA Files’ study on the post-Marcos judicial appointments process.)