By PABLO TARIMAN

A worthy component of “Ikaw Ang Pag-ibig,” the latest film of Marilou Diaz-Abaya, is not just the excellent story and a superb cast but the profoundly moving musical scoring of Nonong Buencamino.

A worthy component of “Ikaw Ang Pag-ibig,” the latest film of Marilou Diaz-Abaya, is not just the excellent story and a superb cast but the profoundly moving musical scoring of Nonong Buencamino.

For instance, the heart-rending strain of a cello played by Renato Lucas can be heard in the part where the family copes with both financial and spiritual crises.

The music sets the tone of the contemporary setting of the story. The film due for release in mid-February just in time for Valentines Day is another proof of the excellent artistic collaboration between the award-winning filmmaker and the musical scorer.

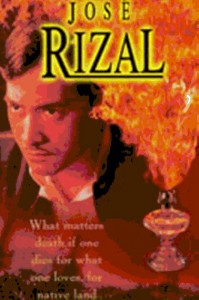

Buencamino’s credentials as film musical scorer were seen in Diaz-Abaya’s other memorable films such as “Jose Rizal,” “Muro-Ami,” and “Bagong Buwan;” Cesar Montano’s “Panaghoy Sa Suba” (Call of the River), which won the top cultural award in the 2005 Metro Manila Film Festival; Laurice Guillen’s “Tanging Yaman;” and Chito Rono’s “Decada 70.”

He has done more than 280 films as musical director plus another 50 in collaboration with Jimmy Fabregas as arranger, orchestrator and contributing composer.

“I wasn’t keeping track of the films I’ve done especially in my early years and now I am having a bit of difficulty putting together my filmography,” he muses.

It is common knowledge that if there is a Nonong Buencamino musical score in any festival entry, chances are he’d always get the award without fail. “Getting an award is a fun thing when it happens,” he said. “To paraphrase Vangelis, one of the pioneers in modern synthesizer scores (e.g. Chariots of Fire), ‘there is nothing wrong with winning awards. What’s wrong is when one works in order to win them.’ I subscribe to this idea in as far as my work (as films composer) is concerned.”

“I used to aspire for awards and get thrilled with winning them in my younger years as film composer,” he admitted. “But that didn’t last very long. Eventually one comes to realize that there are far more meaningful things that happen in one’s professional and creative life than the awards night. When I go inside the theater and observe the audience reacting positively to the stuff that I did on the film, that’s as good as any award I can get.”

“I used to aspire for awards and get thrilled with winning them in my younger years as film composer,” he admitted. “But that didn’t last very long. Eventually one comes to realize that there are far more meaningful things that happen in one’s professional and creative life than the awards night. When I go inside the theater and observe the audience reacting positively to the stuff that I did on the film, that’s as good as any award I can get.”

Nowadays, he would usually attend awards night only to show his support to his colleagues for their worthwhile endeavors. His last attendance was such a show of support for Cesar Montano’s brave and noble attempt in coming up with “Panaghoy Sa Suba.”

Nonong came from the musically illustrious Buencamino clan, which has pianist Cecile Licad as one of its celebrated descendants. Music was this film composer’s stuff since he was a kid. He played the piano since age eight and was taught by no other than Cecile Licad’s mother Rosario, who happens to be his aunt.

He also took violin lessons under his father’s violin teacher Luis Valencia, who is the founder of the Philippine Philharmonic. He stopped piano lessons and turned to the organ and later, to composing pop songs.

His professional music career started as a moderator of the school glee club of Maryknoll College while studying AB major in economics at the University of the Philippines (UP). He dropped out to audition at the UP College of Music.

He was in his first year in the conservatory when his father — who was managing the LVN studios in 1976 — told him that his cousin Mike de Leon was doing a new movie.

“I said I felt I wasn’t ready yet for such a big job,” he recalled. “I suggested a classmate of mine, Jun Latonio, as musical director and I agreed to be the assistant musical director. That’s how my film composing career started.”

Today, the thing that matters to him most is the fact that many directors entrust their films to him.

“More than anything, collaborating with filmmakers is about human relations and good faith because doing films is a collaborative process,” he pointed out. “The easiest to work with of course are those who do not know a single thing about music and just leave it to you to decide. It can also be easy to work with those who are quite knowledgeable on music because at least you’re speaking the same language.”

“The most painfully difficult ones to work with are those who do not have a single ounce of musicality in their system, but still pretend like they were descendants of Beethoven or Wagner,” he added.

He said it takes several things to be a good film composer. Among these, he said, are being sensitive to the needs of every creative department and being able to address them as needed; being able to get a tight grasp of his director’s vision, tempo, intention, and feelings; and being able to connect with his audience.