By YVONNE T. CHUA and ELLEN TORDESILLAS

A FORMER state auditor who testified against ex-military comptroller Carlos Garcia disclosed over the weekend a “request” from a government office for her to tell the public the evidence in the plunder case against the retired major general is weak.

But the request, made about a week after the Sandiganbayan on Dec. 16 allowed Garcia to post bail on the basis of his plea bargain agreement with special prosecutors, has only strengthened Heidi Mendoza’s resolve to reveal what she says is “the truth behind the Garcia case.”

“It is plunder; it is more than P50 million. I am standing by my story,” said Mendoza who left her job at a multilateral bank on Friday to embark on a “truthtelling” mission.

Plunder, the acquisition of ill-gotten wealth of at least P50 million by a public officer, is nonbailable and punishable by life imprisonment.

Mendoza, who headed a special six-member team the Commission on Audit detailed with the Office of the Ombudsman from 2004 to 2006 to investigate Garcia’s transactions, is the lone prosecution witness who told the court that the former comptroller committed plunder.

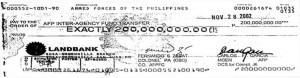

She presented documentary evidence showing that P50 million of the P200 million Garcia had authorized transferred from the Armed Forces’ Land Bank account in Greenhills, San Juan to the United Coconut Planters Bank on Alfaro Street in Makati in November 2002 could no longer traced.

The P200 million represented reimbursements from the United Nations for expenses the Armed Forces had advanced for sending peackeepers overseas. At the time he was charged in court in 2004, Garcia, his wife Clarita and his children maintained a string of bank accounts here and abroad, including at the UCPB.

Despite the evidence, Special Prosecutor Wendell Sulit said the prosecution accepted Garcia’s plea bargain offer because it has insufficient evidence to convict him of plunder.

Under the agreement approved by the Ombudsman on Feb. 25, 2010, the cases of plunder and money laundering will be dropped in exchange for Garcia pleading guilty to lesser offenses of direct bribery and facilitating money laundering.

In the plea bargain agreement, Garcia absolved his wife Clarita and sons Ian Carl, Juan Paulo and Timothy Mark of any involvement in the cases where they were named co-conspirators.

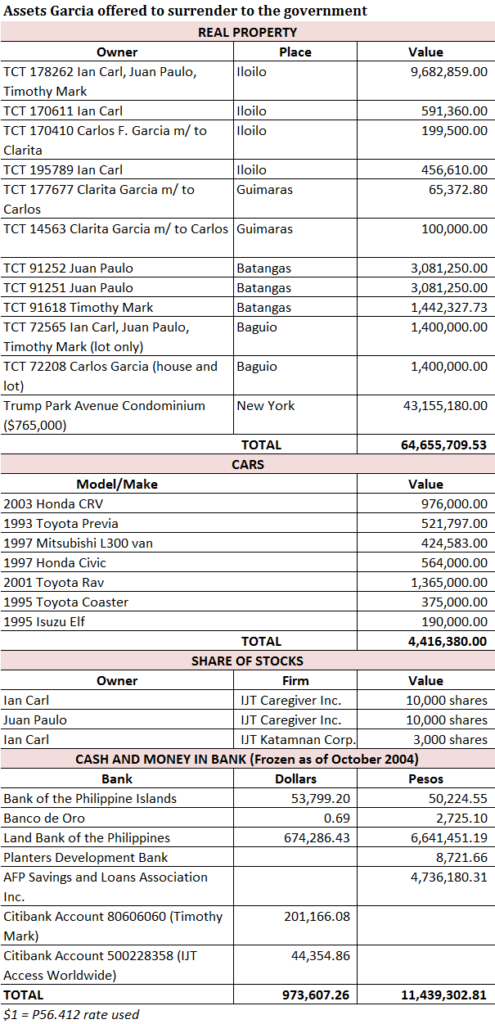

He also offered to turn over real estate properties, vehicles, shares of stocks and money in the bank valued at P135,433,387.84.

Last Dec. 16, Garcia posted P60,000 bail for the two cases he pleaded guilty of and was released from his detention cell in Camp Crame.

Since the special audit began, Mendoza and her team were up against the odds.

Early on, Mendoza received messages to “go slow” on Garcia. “Dahan-dahan lang,” she recalled being told by a government executive.

On another occasion, people within the Armed Forces told her that her investigation was futile because five of her bosses at COA were purportedly receiving favors from the military.

And yet another message asked her to give up trying to pin down Garcia supposedly because there would be no documents that would do so.

But not one to give up, Mendoza and her fellow auditors forged ahead, going over about 90 accounts that involved Garcia.

Finally, one day, afer spending a day and a half in a dusty “bodega” (storage room) of the AFP, she and her team of auditors finally came upon the P200 million transaction.

Finally, one day, afer spending a day and a half in a dusty “bodega” (storage room) of the AFP, she and her team of auditors finally came upon the P200 million transaction.

It was like looking for a needle in a haystack. “Ginulo talaga nila ang files (They really messed up the files),” Mendoza said.

The auditors had to rifle through every folder and scrutinize each document it contained to find the “smoking gun” evidence against Garcia.

Mendoza’s team turned up a memorandum dated Nov. 21, 2002 in which Garcia authorized the opening of an “AFP Inter-Agency Transfer Fund” account with the UCPB in the amount of the P200 million.

The account name itself was already questionable because, Mendoza said, it refers to an entity—the AFP Inter-agency Transfer Fund—that does not exist.

Through an undated disbursement voucher he and Col. Fernando S. Zabat signed, a check in the amount of P200 million and dated Nov. 28, 2002 was issued from the AFP’s Land Bank account and deposited to the newly opened UCBP account. The account was a savings account (No. 132-1121-431-8) linked to a current account (No. 132-002-731-6) with an automatic transfer feature.

Strangely, the check cleared on the same day. The normal clearing period for checks of other banks is three days.

Stranger still was that the entire P200 million was never deposited to the AFP Inter-Agency Transfer Fund account as the disbursement voucher had intended.

Although the endorsement at the back of the check made it appear the entire amount had gone to the AFP account, auditors discovered that only P50 million was placed in Saving Accounts No. 132-1121-431-8 after the check was encashed.

A deposit of P100 million, using the same P200 million check, was instead made to another account: Premium Savings Deposit 1743 (PSD 1743), also at the UCPB Alfaro and whose passbook bore the serial number 347264. The deposit was covered by a savings account deposit slip.

Then there was a third deposit of P50 million, but this time without a deposit slip and to an account numbered also PSD 1743 but whose passbook carried a different serial number (347266). In short, the P200 million check was split into three deposits, and all three transactions happened in a single day.

The third passbook with the serial number 347266 for the second PSD 1743 to which the P50 million was purportedly deposited was submitted by the AFP for audit and was supposedly issued also by the UCBP Alfaro branch.

But Mendoza and her team would later confirm that the passbook not only bore tampered entries but was “fictitious and could not be identified.” A letter from UCPB Alfaro admitted that this particular savings account did not exist in its system.

The auditors instead traced the account to the UCPB branch on Tordesillas Street in Makati. “Said acts cannot be consummated without the participation of bank officials,” they said.

This discovery “raises indelibly the question of where the P50 million supposedly deposited under PSD 1743 with Serial No. 347266 had gone,” said the Office of the Solictor General in its Jan. 5 motion seeking to intervene in Garcia’s case in a bid to nullify the plea bargaining agreement the retired general struck with the Office of the Special Prosecutor. “It must be borne in mind that the accused played the singular role of authorizing the opening of the AFP Inter-Agency Transfer Fund Account, of being one of the two signatories thereof, of splitting the P200 million to be deposited into different accounts, contrary to the intention of the disbursement voucher.”

This discovery “raises indelibly the question of where the P50 million supposedly deposited under PSD 1743 with Serial No. 347266 had gone,” said the Office of the Solictor General in its Jan. 5 motion seeking to intervene in Garcia’s case in a bid to nullify the plea bargaining agreement the retired general struck with the Office of the Special Prosecutor. “It must be borne in mind that the accused played the singular role of authorizing the opening of the AFP Inter-Agency Transfer Fund Account, of being one of the two signatories thereof, of splitting the P200 million to be deposited into different accounts, contrary to the intention of the disbursement voucher.”

Mendoza’s special audit also found that despite the existence of three passbooks for the AFP Inter-Agency Transfer Fund account at UCPB, only Savings Account No. 132-1121-431-8 appeared in the Armed Forces’ books of account and was covered by the annual audit.

Even then, it found the passbook for this account had been tampered to hide transactions that occurred between May 20 and Aug. 17 in 2004.

A 2007 report written by VERA Files trustees Luz Rimban and Yvonne Chua on corruption in the Armed Forces said the COA team detected from a bank statement it obtained from UCPB Alfaro that transactions involving P86.4 million in debit and P34.3 million in credit were “deleted” from the passbook the AFP had submitted for audit. The deletions resulted in a P52 million discrepancy in the account balance.

[Read Rimban and Chua’s 2007 reports on corruption in the military when Garcia was comptroller: AFP modernization drive sputters; Favored suppliers bag AFP deals; RP peacekepers dealt unkindest cut of all]

About P22 million of the “deleted” entries covered payments to 11 suppliers. Another entry purged from the Alfaro passbook pertained to P36 million moved on May 20, 2004 to the AFP’s new account at UCPB-Salcedo and ended up as payments to mostly the same suppliers, some of whom had the same addresses, bank accounts or representatives.

In 2006, after 22 years as state auditor, Mendoza resigned her job over COA’s lack of support for the investigation.

It was COA Chairman Guillermo Carague, on the request of then Ombudsman Simeon Marcelo, who signed in October 2004 an office order detailing Mendoza’s team to the Office of the Ombudsman.

But COA did not even want as much as an update from her team. Mendoza had asked COA officials in the middle of the audit if they wanted a progress report, and was bluntly told they were not interested.

By the time she was taking the witness stand in Garcia’s trial, Mendoza was no longer in government but employed by a multilateral agency. To her surprise, Carague, despite having signed the 2004 office order, wrote the court to deny he had authorized the audit. Carague was not summoned to the court, though.

But what made Mendoza really restless was when the Sandiganbayan granted Garcia bail last month. And then the “request” came.

Mendoza said when she left government service, she had turned over to the Office of the Ombudsman a dozen balikbayan boxes of documents she had gathered on Garcia, including those on the P200 million check. Prosecutors, she said, had no reason to say the evidence against the former comptroller is weak.

“What I have are memories and a few scanned images of (Garcia’s transactions),” she said. But all these remain vivid, she added.

In a separate interview, former Ombudsman Marcelo, who initiated the cases against Garcia, also debunked the argument of prosecutors that the handwritten statements given by Mrs. Garcia to U.S. customs agent Matthew Van Dyke when she and her sons were accosted upon entering the U.S. with $100,000 cannot be used as evidence because aside from being unsworn, as co-accused she cannot testify against herself and her husband under the rule on marital privilege.

Mrs. Garcia had identified military contractors as among the sources of her husband’s wealth.

Marcelo said the rules of court allow the extrajudicial admission of a conspirator against a co-conspirator.

“All you have is to present the person to whom the statement was made to authenticate the statements,” he said. A sworn statement is not even needed as a verbal statement would do, he added.

Marcelo also said he was willing to support Mendoza’s decision to go public.

Recalling the risks she had exposed herself, her family and friends to for going up against Garcia, Mendoza, who is 48 and a mother of three, said the former comptroller once angrily called her a “liar” after a court hearing and warned her, “There will be a time of reckoning.”

But she is not one to just back down. “I can’t accept that six years of my work, of my life, would just be thrown out like that,” she said.

On Dec. 23, Mendoza turned in her letter of resignation to the bank where she had been assigned anticorruption projects. “It’s difficult to lose a job, but I also can’t hide behind the comforts of my job and allow people to be misled,” she said.

And sitting down and doing nothing, she said, would render her work for good governance meaningless.

The former government auditor is unsure how the Sandigbayan would eventually decide the Garcia case. But of this she is sure: “I want people to have a collective stand against corruption and show that we are serious in fighting corruption. Even if we lose in the courts, manalo tayo sa kapwa tao (let us win as a people).”

Garcia Plea Bargain

OSG motion in Garcia plea bargain