PART II

The small fishers’ claim that big operators are competing with them in municipal waters has been belied by the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) Bohol.

Mark Antony Milana, BFAR Bohol Coastal Resources Management section, objects to the view that commercial fishing boats have a disadvantageous effect or impact on municipal fisher-folks since he claims that they fish after 15 kilometers from the municipal shore.

“If they go there (municipal waters), they could not proceed because there are ‘floating assets’ (informers) there,” Milana explained.

The municipal LGUs, he pointed out, have been mandated to regulate fishing operators in their town, from the coastline up to 15 km, adding that if enforcement is weak, there is a tendency for commercial fishers to intrude in their waters.

At the municipal level, there are fishery ordinances on what distance is allowed for commercial fishers to operate, including the size of mesh nets. Once the local fishers apply for a fishing license, the LGU checks their gear, according to Milana.

Active fishing gears

Commercial fishers like Eugene Lopecillo, boat owner/operator, and Jesus Bensig, boat captain, use purse seines in their operation which are considered “active gears,” says Milana. These are characterized by gear movements in pursuing target species. It involves towing, lifting and pushing the gear, surrounding, and scaring the target species to impoundments, such as a trawl, purse seine, Danish seines, and drift gill, Milana explains.

Purse seine fishery usually operates in deep waters through the aid of fish aggregating device (FAD) called “payao”, often installed adjacent to a reef. The payao consists of a buoy, mooring line, anchor and attractant (habong), usually made of coconut or buri palm leaves, shares Epifanio Gultia Jr. of BFAR Bohol.

The payaos aggregate smaller fish in pelagic or surface waters, such as anchovies, mackerels and sardines, he says, adding that they aggregate bigger bottom-dwelling fish, such as slipmouths, spadefishes, groupers, and catfishes in demersal waters.

There are payaos set up by municipal fishers’ organizations, which use handlines or hook and line when fish aggregate in the payao. In fact BFAR Bohol provides materials for payao set up by some small fishers’ organizations.

Purse seines and ring nets catch mostly oceanic pelagic fishes, such as round scads, small tunas, big-eye scads, small tunas, etc., according to BFAR’s data on fishing methods and gears.

As active gear, the purse seine and ring nets are prohibited within 15 km from the municipal shoreline because of its capacity to scoop the fish, including juveniles, and to prevent them from damaging the fish habitat corals, BFAR sources said. However, they can be used after 15 km from the shore. The Philippines has an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 200 miles from its shores.

Restriction in intensity of light

There is a restriction in the intensity of light used by commercial fishing boats, especially the use of “super light” or “cold magic light,” referring to the use of light using halogen or metal halide bulb, which usually attract even the juvenile fish, notes BFAR’s Gultia. It is, however, allowed after 15 km from the municipal coastline, he adds.

Each month, the commercial fishing boats are required to give a report of the volume and species of their fish catch.

Common violations of commercial fishers

The PNP Maritime Group Bohol has a mandate to protect the Bohol Sea and to apprehend those who are involved in illegal fishing or using “active gears” on unauthorized waters or those using destructive fishery methods, says Police Chief Master Sergeant Jarlyn B. Elopre.

In an interview with Maritime Group Bohol’s PCMS Elopre in Tagbilaran, the common violations of commercial fishers in Bohol include the following:

- Intrusion in municipal waters or violation of Section 86, Republic Act 8550 as amended by RA 10654;

- Use of active gear, like the purse seine (likom) or ring net or hapa-hapa within prohibited waters;

- Use of prohibited trawls or liba-liba, particularly in the northern part of Bohol (Talibon);

- Use of superlight, noting that the fishing light attractor used disturbs the fishing ground, and could even draw small fishes.

Among the apprehended were those who went beyond their permitted fishing ground, had no proper permit or had expired license to operate, and those engaged in destructive fishing practices, she adds.

Before filing a case, the office first asks BFAR to certify if the gear are “active” or prohibited within the area, after which, more details are gathered. A case is then filed in specific Municipal Trial Courts.

In the case of the recent apprehension for use of superlight, an administrative fine of P2,500 ($44.64) is meted out. If there were four persons involved, that’s a total of P10,000 ($178.571) fine, depending on the judge’s decision, a Maritime Police Station source said.

A former PNP Maritime Intelligence operative says based on experience, when a boat is apprehended for fishing within the 15 km municipal water, the owner usually requests that the case be placed under the municipal court.

When that happens, the owner uses his connection with town officials or employs “standard operating procedure” like giving fishery products to enforcers, to avoid the law. He was operating in regions 8, 6 and 7, and from his experience, the big fishing operators are just fined at the municipal level.

He adds that the problem with the 15 km prohibition is that the makers of that law were just sitting on their desks when they made it, and did not check the actual ground situation of an archipelago which has a lot of overlapping island boundaries. In some cases, the boundaries of the islands are too near and overlap and do not reach 15 km.

He, however says that the boat operators know the distance among the islands. They have been in the business for so long. After three violations, their case is brought to the national level where the fines are bigger.

Detecting intruders in municipal waters

The Global Positioning System (GPS) in the only patrol boat of the province detects commercial fishing boats that venture within the 15 km radius of municipal waters. Once detected, their direction is plotted, Police Officer Velayo of Maritime Group Bohol said.

Showing the GPS in the patrol boat, officer Velayo said red spots on the screen indicate that fishing or other boats have entered inside the municipal waters. Yellow spots mean the boats have moved away.

Information can also come from complaints. Some informants call the maritime group’s office to report those fishing with light attractor, he added. Concerned citizens and small fisher-folk are the ones who complain because their catch are greatly affected, PCMP Elopre shared.

Once they detect violators, and get ground confirmation, they plot their location, then prepare for a patrol operation to apprehend them using the 3-engine patrol boat.

Local ordinances for fishery sector: the case of Baclayon town

Municipal governments can make fishery ordinances to protect small fishers and their marine resources in support of the Fisheries Code. There are a number of coastal towns with ordinances related to fisheries protection and production. But their implementation is another matter. The case of Baclayon is discussed below to illustrate that.

Erico Canete, secretary to Baclayon municipal council, disclosed that ordinances have been enacted for the fishery sector of his town aimed at conserving, protecting and ensuring the sustainable management of the town’s fishery and aquatic resources, as well as alleviating poverty among small fishers.

Municipal Ordinance # 3-2007 vows “to protect municipal fisher-folk against intrusion into municipal waters of commercial fishing vessels and illegal fishing activities.” It prohibits the use of fishing boats’ active gear in its waters.

A violation will be punished with a cancellation of fishing permit, confiscation of fishing equipment and catch, and a fine not exceeding P2500 per person or imprisonment not exceeding 6 months. “The owner/operator of the fishing boat used and all the crew and workers thereof shall suffer the same penalty.”

It also spells out a procedure for monitoring, control and surveillance of municipal waters. It includes the formation of a composite team of PNP, POG, Maricom and deputized Fish Wardens/Bantay Dagat to conduct seaborne patrol operations in the town’s waters.

Deputized fish wardens/Bantay Dagat are responsible to monitor activities covering municipal waters of Baclayon with regards to environment and fishing activities, and to provide assistance in search and rescue operations. There are two surveillance motorboats (30 ft. each) for this purpose.

Despite the ordinances, however, small fishers experience continued intrusion by big fishing boats in their municipal waters.

San Roque, Baclayon. Jose Basalute, 49, with 2 children, a small fisher from San Roque village of Baclayon town, checks his motorboat on a breezy day in July. On a clear day, he usually goes to sea at 5 pm and returns at 4 am the next day so that the fish could be sold fresh on roadside fish stalls.

Sustenance fishers like him often get burot-burot (red tail), anduhaw (Spanish mackerel) and tulingan (frigate tuna) these days. “The most we get is 3 to 4 kilos when we go fishing. If you take the initiative and get back to the sea, you can’t get 5 to 6 kilos because fish has dwindled. They take them all.”

When asked to explain, he cites the “lantsa” or large fishing boats as their biggest problem, saying such boats compete with the small fishers.

“Our fishing operation—by pukot or net and hook and line, is on a very small scale, theirs is on a big scale,” he says. “Once they drop their net and surround the payao, they scoop up all the fish. Nothing is left for us. We have nothing to get back to.”

“The worse thing is that even the small fish, those that are only fingerlings become part of their catch. Fish that are as small as the small finger are already taken in the net. If we have a payao, we just use our hook and line, and leave the small ones.”

“Our agreement is that those big fishers could fish only beyond the 15 km limitation, but who will check or question them in the middle of the night? No one watches their operation at night,” Basalute adds.

“It’s always been like that. When those fishing boats drop the net (mag-arya), they take all the fish. We want to find a solution. The payao has a financier, even the ones who spot or detect the school of fish, they are all part of an operation.”

He sees their fishers’ organization with 37 members hope to find a solution to the problem and to have a fair sharing of and access to resources. That is why they are trying to register their group with the municipal labor office of Baclayon.

Basalute adds they know that the big boats are not supposed to put a payao in the municipal waters, but they could not complain “because the financier is in a position of power (naa sa katungdanan).”

“Aron makuha nila tanan, sug-an nila ang payao pagkagabii ug kusog nga suga, that way the fish will gather. (So that they can get all, they use strong light in the payao so that the fish will gather).

“Usa ra ka aryahan sa pukot nga taas kaayo ug duot, so hurot gyud tanan. Way mabilin tanan isda. (Just one laying of the net which is very long and deep. Nothing is left of the fish).

“They are fishing very near here. The big boats are not following the fishing limitation.”

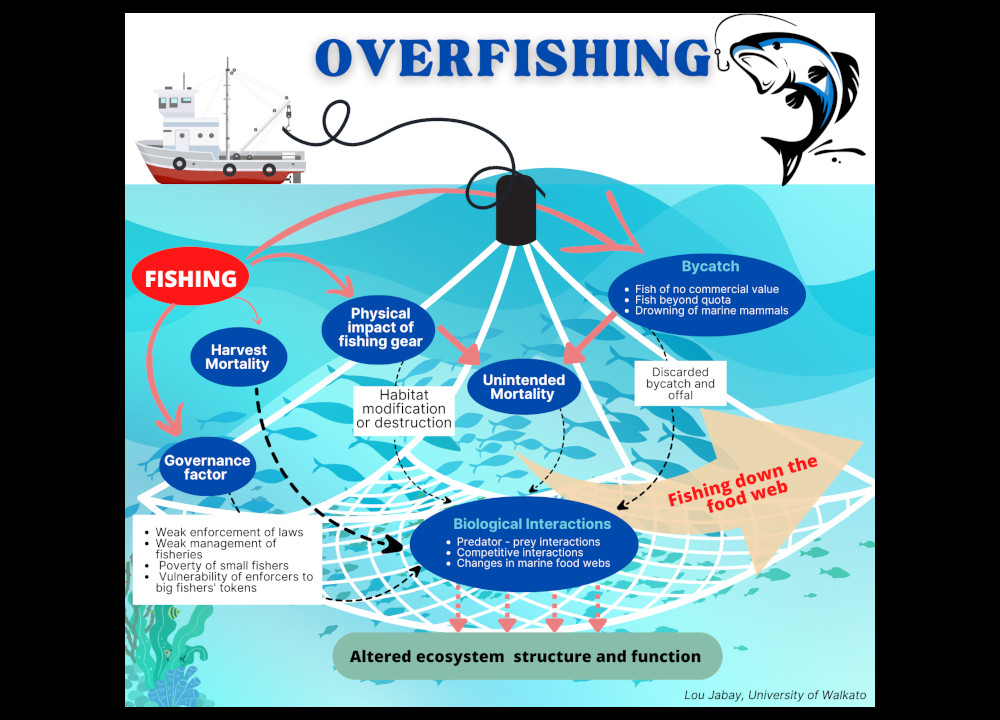

Practice and trends leading to overfishing

A study by Stuart Green, et al, (2004) on “The Fisheries of Central Visayas, Philippines: Status and Trends” noted that there had been a shift, not only in the volume of catch, but also in the quality of fish in the region, adding that there had been an overall shift of catch away from shallow water to oceanic pelagic species and away from demersal to pelagic species.

By the late 80s, tunas had been replaced by the round scads which are much lower in the food chain and of less value and quality, but more resilient to overfishing, the same source noted.

In the 80s, “the coastal pelagics have replaced the demersals as the most abundant catch and the invertebrate species have shifted from shrimp dominant to squid dominant—illustrating a shift in the ecosystem due to fishing pressure and a shift away from trawling to purse seine and ring net,” Greene’s study observed.

Crescente Bernaldez, Baclayon MAO Fisheries focal person, observed that the purse seine net used by big fishing boats are arranged in three layers—from the biggest at the top, the medium size in the middle, and the smallest size at the lowest level (12 mm)—that it tends to capture the juvenile fish.

He also noted that commercial fishers resort to fishing in municipal waters because that is where they find fish, both pelagic and demersal, adding that a number of them find themselves searching for nothing in the high seas.

Other observers notice that fine meshed nets also tend to capture small, juvenile fish. Some of these are used in the “bulsa” or pockets in the “bunsod” or fish corral of municipal fishers.

Migration path and feeding ground of large mammal vertebrates

The Bohol Sea serves as a migration “highway” and feeding ground of blue whales, dolphins, whale sharks and manta rays, and recently even Orcas have been spotted there.

From reports and dedicated studies, it appears to be part of the habitat or migration path of cetaceans and large marine vertebrates.

These marine vertebrates are sighted during periods of high ocean productivity between January and June. Sightings of some species, like the sperm whales have been regular for the last 15 years.

Accounts from fishers and dolphin tour operators in Pamilacan Island mention the presence of large whales locally known as “bongkaras” between January and June.

The “bongkaras” or Bryde’s whales and sperm whales have been historically hunted in coastal areas fronting the Bohol Sea.

In surveys conducted in Northern Bohol Sea (Ponzo) from 2010 to 2013, the melon-headed whale stood out as the most encountered species, followed by Frazer’s dolphins and spinner dolphins.

Fishers from Dauis, Lila and Baclayon towns have attested to have seen a pod of up to 200 dolphins in their coastal waters.

Based on dorsal fin markings, some individual melon-headed whales have been photographed in Bohol Sea in all four years (2010 to 2013), “suggesting some degree of residency,” or regularity of visit in the area, the same source notes.

On the elusive blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus), its presence in the Bohol Sea was noted in 2004, but it was only in 2010 that the species was documented and photo-identified. All sightings of the blue whale took place between February and June.

Finding the Blue Whale within the Bohol Sea, north of Indonesia, could mean that the Philippines, and the Bohol Sea in particular, may be an extension or part of the northern migration path of the Indo-Australian population.

Monitoring through satellite tagging of whale sharks in Donsol, Sorsogon, and Sulu Sea, found that “whale sharks spend more time in deep waters, with the area of the deepest dives at over 1,400 m recorded in the Bohol Sea.”

A position paper by the Save Sharks Network Philippines noted that if the marine vertebrates “do not migrate to their deep habitats or the next feeding area, which are possibly mating and spawning grounds, they will be unable to perform their ecological roles in these ecosystems.” It concluded that as “endangered species…they need all the reproductive opportunities they can get.”

Their migration pattern is interrupted, and their movement restricted when an “ecological trap” is created when, for the sake of tourists, they are lured by feeding them krill, for example (as in the case of Lila town’s whale shark interaction). This “alters their ecological roles and ecological needs.”

Indicators of overfishing in Bohol

Villa I. Pelindingue, Coastal Resources Management Division Head of Bohol Provincial Environment and Management Office, points at some signs of overfishing.

“In some areas, even if coral reefs are healthy and in good condition, there is minimal fish presence and there is low species diversity,” Pelindingue says. As an example, she cites their study in Mabini town that has been found to have good coral reef status, but with less fish diversity.

“When you see non-target (not in demand) fish, or fish not valued in the market, like the damsel or butterfly fish, instead of tuna or tamarong, that’s another indicator,” she points out.

Another sign, she shares, is “when it takes more time to catch fish, and yet there is less catch, and…the presence of small fish in the market.”

There is also the “upgrade” of the former un-motorized boats to motorized boats since the fishing ground is now far from the shore, unlike before when the fishers can just row to a fishing ground nearby.

Less use or “retirement” of certain gear for fishing certain species since they could not catch what they used to get, is another indicator of overfishing, adding that the use of fine meshed nets for fishing or the double or triple net phenomenon suggests that fish sizes have become smaller.

A sure sign, she says, is the entry of commercial fishing vessels in municipal fishing ground, when they should be fishing in the high seas for bigger fish.

Overfishing impact on marine ecosystems and marine mammal population

The interaction among the various players of the fishing industry– the commercial fishers, sustenance fishers, local government units, enforcers and those tasked with managing the marine resources– has a bearing on the state of the marine ecosystems and condition of fish stocks that could affect the food web and coastal communities near the Bohol Sea.

Intensive commercial fishers’ operation and harvesting of resources from the waters of Bohol Sea, as experienced by municipal fishers themselves, can lead to overfishing—whether due to weak enforcement or use of active fishing gear—and affect the food chain leading to the large marine vertebrates and other marine creatures.

Unregulated commercial fishing can impact on a marine mammal population, first, by “depleting localized food resources without necessarily overfishing the target species of fish (or shellfish). This causes the reduction of extant populations and species richness of marine mammals.”

“Overfishing can impact on entire ecosystems. It can change the size of fish remaining, as well as how they reproduce and the speed at which they mature,” the same source says.

When too many fish are taken out of the ocean, “it creates an imbalance that can erode the food web and lead to a loss of other important marine life, including vulnerable species, like sea turtles and corals,” it adds.

Overfishing can bring about a number of effects on the marine population. They include:

- Massive depletion of many fishes;

- Loss of breeders, thus fewer young produced and increased risk of reproduction failure in times of poor environmental conditions (like unusual ocean temperatures);

- Declines in average sizes of fish and other marine creatures;

- Loss of genetic diversity;

- Genetic change toward less desirable characteristics, like smaller size potential;

- Disruption of natural communities; and

- Disruption of human communities.

“The reduced abundance of top predators may release smaller predators that in turn control abundance of herbivores and thereby altering organisms near the base of the food web,” according to the same source. For example, the removal of algae-eating fishes can cause coral reefs to be killed by algae overgrowth, especially in tropical regions.

Alvin Simon, marine scientist of Oceana, a non-government international ocean conservation advocacy group, went as far as saying that overfishing “may induce ecological collapse since it tends to erode the food web which can lead to the loss of other important marine life, including those that are vulnerable, such as marine turtles, sharks, marine mammals and other megafauna.”

Suggested moves to prevent overfishing and increase fish stocks

Niva Gonzales, marine biologist and chairperson of the board of Center for Empowerment and Resource Development (CERD), says that preventing overfishing will entail enforcement of the law on illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

Another way is to empower communities to manage their resources, including giving them incentives to monitor unsustainable fishing operations. Even municipal fishers may contribute somehow to overfishing with the use of fine-meshed nets, for example, Gonzales observes, but adds that the scale is just bigger in the case of commercial fishers.

She supports the implementation of an informed fisheries management using the ecosystems based fishery management (EBFM) approach; creating marine protected areas; and declaring a closed season during the spawning period of specific species.

Pelindingue suggests that overfishing can be prevented, or fish stocks increased, if there is protection and conservation of marine resources, particularly coral reefs, sea-grass beds and mangrove forests, which are the habitats and spawning grounds of marine fauna. From their initial investigation, these resources were greatly damaged by typhoon Odette.

Another move is to strengthen the management of marine sanctuaries. If there’s a closed season, there must be research on species’ spawning season.

Furthermore, she says there should be strict enforcement of laws and policies to protect local fisherfolk, as well as put an end to illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing.

Closed Season

Dr. Vincent Hilomen, Marine Key Biodiversity Areas project manager of DENR calls for a moratorium, where some fishing grounds are closed for the development of marine protected areas (MPA), representing 15% of the fishing grounds. Fish stocks must be allowed to accumulate biomass there, he said.

In a study in areas in the country where there were “upwelling” or “an area where nutrients from the sediments are brought up because of water movement,” it was found that the nutrients comprise nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium (NPK), Dr. Hilomen said. When these nutrients are abundant, it triggers the growth of plankton, too tiny to be eaten by the fish, he added.

The zooplankton eats the plankton before the small fishes eat the zooplankton, and the bigger fishes eat smaller fishers, and so on, he explained, adding that this is the food chain. Out of these nutrients made of NPK, the plankton quickly grew when they waited for three weeks to a month in an upwelling area. The fish population in the area increased, he said.

The point is to allow the fish to mature and to spawn before catching it, Dr. Hilomen reiterated.

Some parts of Regions 5, 6, and 7 (northern Cebu) have a ‘closed season” when they have a ban on fishing certain species to allow them to spawn, starting November 15 to February 15, which are considered as spawning period for sardines, mackerel, scads and herring, BFAR’s Gultia said.

Yearly, before the closed season starts on November 15, an information drive is conducted in those areas where a moratorium is enforced.

There had been no closed season for any species in Bohol.

Watch:

Diminishing Catch in Bohol Sea Waters

“Kinabuhing Mananagat” (Fishers’ Life)

This story was produced with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network’s Ocean Media Initiative 2022.