Part I

The blue-green water becomes increasingly deep blue, and the wooden boat sways up and down as though pulled by a powerful force, then salty water splashes as it heaves up with a big wave.

From a distance, there appears some gurgling on the otherwise silky water, then back fins of dolphins start showing a few meters from the boat, delighting the passengers!

The Bohol Sea found north of Mindanao Island with a coastline length of 273.3 km is considered one of the Philippines’ important marine heritage sites, where rare species of sea turtles, manta rays, seahorses, giant clams and a wide variety of molluscs are found.

It is frequented by important pelagic fish and whale sharks. Its surrounding deep sea is known as a migratory route for whales and dolphins, and possibly their feeding ground too, says Villa I. Pelindingue, Coastal Resources Management Division Head of Bohol Provincial Environment and Management Office.

Considered “a biodiversity hotspot for cetaceans in the Philippines and Southeast Asia”, it is one of the richest fishing grounds in the country, where 23,357 registered municipal fishers from 18 towns regularly go fishing for a living using different ways and gears, according to the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Bohol. They represent some 37% of the total 63,106 registered municipal fishers in the island province.The condition of the Bohol Sea has been attributed by scientists to its distinct topography and the peculiar movement of the water that causes “upwelling” which brings nutrients to the surface. “The Bohol Sea’s connections with deep basins, the Pacific Ocean to the East and the Sulu Sea in the West, give it ‘unique circulation and physico-chemical properties,’” according to Jo Marie Acebes in The Journal of Threatened Taxa.

“Furthermore, the water movements—sea surface currents, formation of eddies, and entrainments—cause upwelling and brings seasonal variations in productivity, food supply, and subsequently, fish abundance in the Bohol Sea,” adds Acebes, senior researcher of the Zoology division of the National Museum of the Philippines.

The sea’s unique underwater topography and water upwelling feature draw cetaceans and other marine species to the Bohol Sea as their feeding ground and migration highway.

Some 19 marine mammal species have been sighted in this sea, including the blue whale, dwarf sperm whale, melon-headed whale, short-finned pilot whale, Risso’s dolphin, Fraser’s dolphin, spinner dolphin, pantropical spotted dolphin, beaked whale, Blainvilles’s beaked whale, Bryde’s whale, rough-toothed dolphins, among others.

The Bohol Sea covers a total area of 7,968 square km, and the area beyond municipal waters covers 4,230 square km. The marine ecosystems within such waters are linked together and are fluid for pelagic and demersal fish to go in and out without administrative boundaries and become part of the natural food chain.

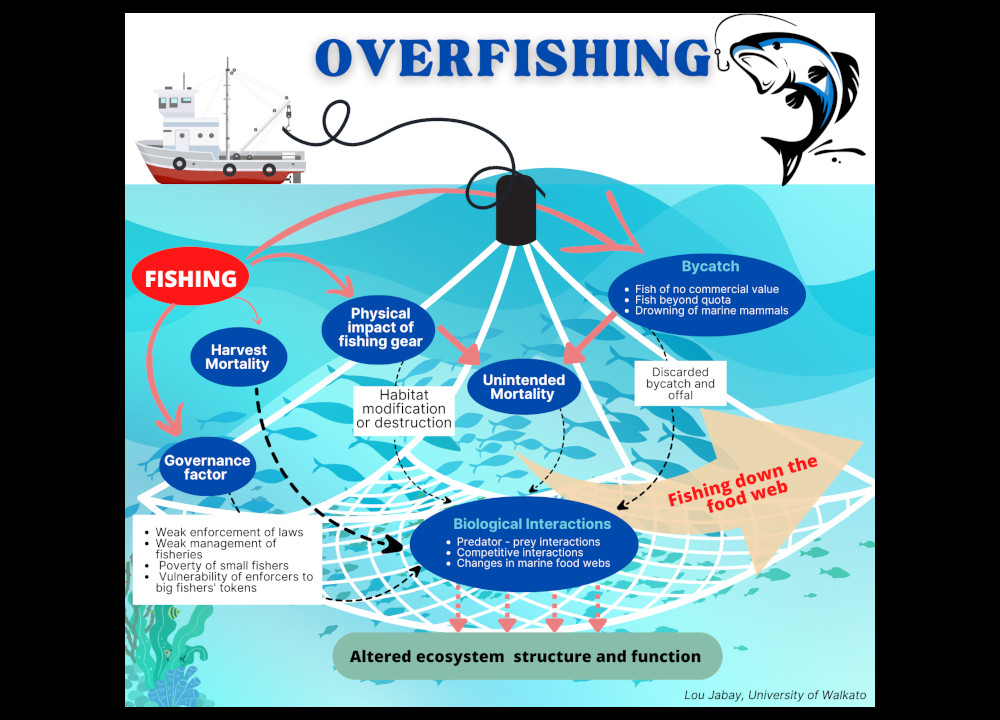

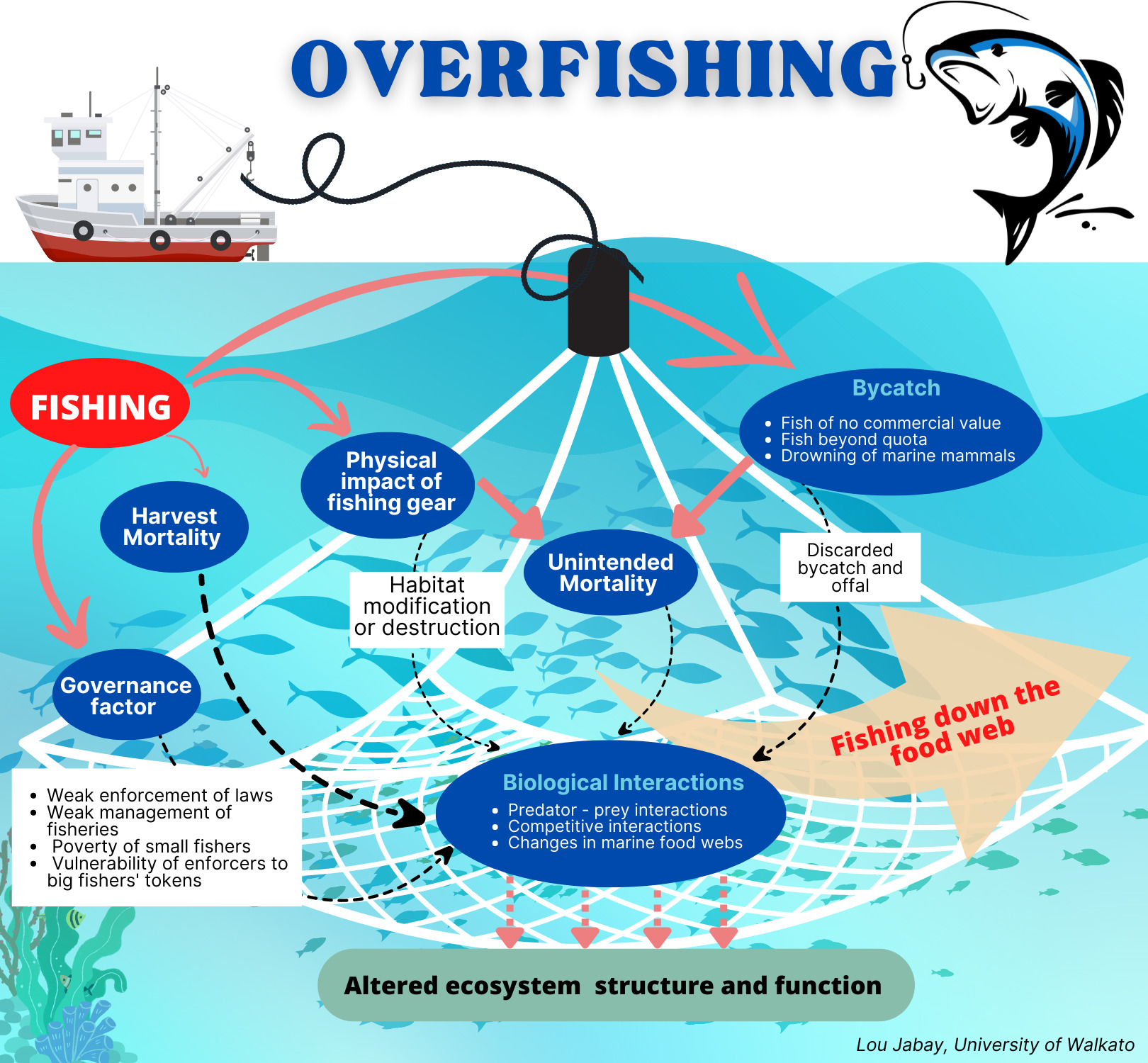

Untrammelled exploitation there, and around the island province, however, leads to overfishing, which involves the removal of a species of fish from a body of water at a rate greater than the species can replenish its population naturally which result in the species becoming underpopulated in that area, says marine biologist Niva Gonzales, and board chairperson of Center for Empowerment and Resource Development (CERD).

Once overfishing takes place, whether in pelagic or demersal waters, it breaks the natural flow of the food web, which in turn, affects not only the marine mammal vertebrates, but also the coastal communities, Gonzales adds.

Commercial fishers Eugene Lopecillo, a boat/owner operator, and Jesus Bensig, a boat captain, who regularly draw from the vast resources of the waters around the island province, admit their fish catch is diminishing, but say the Bohol Sea still teems with fish enough for fishers and marine mammals who make it their feeding ground.

Sustenance fishers from towns facing the Bohol Sea, however, bewail that big fishing boats continuously “intrude” in their municipal waters, scooping the fish there, including the juveniles, which leaves them hardly enough to survive on in overfished waters.

Aside from municipal fishers, 29 commercial fishing vessels currently operate in the Bohol Sea and other nearby waters, 21 of which are classified as small scale commercial fishing boats with active gears utilizing vessels of 3.1 gross tons up to 20 gross tons, and 8 medium scale commercial fishing boats that use active gears and vessels 20.1 gross tons up to 150 gross tons (BFAR, 2022). Ten have purse seines or with motor-driven nets, while 19 have ring nets or manually-operated nets.

Encounters with marine mammals in the sea take place during a period of high productivity between February and June.

Some 19 marine mammal species have been known to occur in this sea, including the blue whale, dwarf sperm whale, melon-headed whales, short-finned pilot whales, Risso’s dolphins, Fraser’s dolphins, spinner dolphins, pantropical spotted dolphins, beaked whales and Blainvilles’s beaked whales, Bryde’s whale, rough-toothed dolphins, among others, sometimes when they follow the same school of fish tracked by commercial fishing boats, or while on a tour in a site they converge in, or during “interaction moments” with whale sharks a few meters from the shoreline of a village.

The presence of the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) in the Bohol Sea was noted in 2004, but it was only in 2010 that the species was documented and photo-identified. All sightings of the whale species took place between February and June.

Finding the blue whale within the Bohol Sea, north of Indonesia, could mean that the Philippines, and the Bohol Sea in particular, may be an extension or part of the northern migration path of the Indo-Australian population.

Dauis, Bohol. Boats carrying vats of fish start arriving early morning in mid-June at the fish port of Tabalong village of Dauis town, some 6 km from provincial capital Tagbilaran. Buyers meet the boats, some proceeding to weigh the fish they want to buy, haggle for the best price, and then move them to trucks where they are placed in coolers with crushed ice.

From a distance, one sees a small commercial fishing boat with a neatly dressed man on its prow near the anchor winch who appears to be cooking, and some men pounding metal near the machine.

Eugene M. Lopecillo, 48, owner and operator of F/B Snr. San Vicente Ferrer EVL, an 11.45 GT fishing boat, says he has not gone fishing since the boat’s machine and purse seine net are being fixed.

He bought the fishing boat in 2013 with a P 7 million ($125,000) loan which he recently has just fully paid. Lopecillo’s boat falls under the small-scale commercial fishing boat category.

When he goes out fishing, he needs to bring 28 people to operate the machine and the net. His boat is equipped with a fish finder he bought for about P8000 ($142.85). It detects fish just under and around the boat. There is a sonar fish finder that detects fish as far as 1.2 kilometers, but it costs P7 million that he cannot afford at the moment.

He explains the mechanics of the purse seine which pulls the net mechanically through a “ferris wheel” pulley. It takes only two hours (to raise the net) compared to the manual ring net gear, “this way we avoid being delayed and possibly being stranded during a typhoon,” he says.

He recalls catching tuna when he started some 20 years ago, but those days are gone. These days, they catch lots of anchovies, burot-burot (red tails), tamban tuloy (sardines), malangsi (flying fish), tulingan (frigate tuna), and tamarong (big-eyed scad), he shares.

When the sea is calm, sometimes they encounter big marine vertebrates, such as whales, dolphins and whale sharks, especially when there are schools of fish, like anchovies and sardines. The big fish follow the small fish and feed on them. Fishers avoid being entangled with the big marine mammals as their nets, which cost more than P1 million ($17,857.14), could get ruined. They are released if they become entangled with the nets.

These large marine mammal species are spotted in the Bohol Sea area at a time when there is a proliferation of krills, planktons and anchovies, usually between January to June. They are highly mobile species that swim to Taiwan, Malaysia and Indonesia. As observed, they migrate seasonally between areas as this allows for nutrient exchange.

In the case of the blue whale, all sightings took place between February and June, suggesting that “blue whales in the Philippines may extend the outer range edge of the Indo-Australia population that migrate between Western Australia, Indonesia, and East Timor.”

In Lopecillo’s view, the sea still teems with fish enough for both the fishers and the mammals.

“They say there are too many fishers, that there’s not enough fish for everyone. I see there’s still many fish in the sea,” Lopecillo says. What is needed, he adds, is to settle boundaries and for give and take (among stakeholders) for the sake of families who depend on the sea for a living.

The problem, he says, is that they “cannot fish properly because there are these laws that prohibit us, and we can hardly move given the archipelagic nature of the islands.” For example, he points out that there’s just about 28 kilometers between Cebu and Bohol islands.

“If we exceed 15 km., those in Cebu will arrest us. If those in Cebu fish near Bohol, they get arrested. There are simply too many overlapping boundaries to be resolved,” the boat owner/operator notes.

Coastal communities depend on marine fisheries ecosystem

Bohol has a total of 47 municipalities and a city, 30 of which are coastal towns. Of the total population of 1.394 million in 2020 from the National Statistics Office, some 33% are directly dependent on the marine fisheries ecosystems for livelihood, either as full time commercial fishers or sustenance fishers and gleaners. There are those involved in ancillary industries related to fishing such as fishing gear trading, fish sellers, and fish processors.

The province with its known diverse ecosystem has maintained some 69,614.2 has. total coral reef area and 9,292.2 has. mangrove forest. The major aquaculture fishery commodities produced include seaweeds, finfishes, shrimps and oysters.

In the government’s registration system aimed at regulation, the fishing boats that are three gross tons and above are to be registered and licensed through BFAR. Boats that are three gross tons or below are to be registered with the municipal government.

Small scale fishing boats are stationed at Tabalong, Dauis, Causeway, Tagbilaran and Catarman, Dauis, while as much as eight medium-sized boats are docked at the Loay Port. In their registration sheet, all of the fishing boat owners and operators placed Bohol/Mindanao Sea as their fishing ground, all within Philippine territory.

Fishery production contribution

With its 2.2 million square kilometers of marine water, including its exclusive economic zone, the Philippines stands as a major contributor to world fisheries.

According to the 2020 data from BFAR, total production from its three fisheries sectors—municipal, commercial and aquaculture—reached 4.42 million metric tons, putting the country among the top 10 fish and seafood producers in the world.

Out of its total fish production, around 464,428 MT or 10.5%, goes to export, and the rest goes to local consumption and other uses, according to Frazen Tolentino-Zondervan (15 May 2022) in Ocean and Coastal Management.

The Philippines exports fish and seafood products to the United States (20.6%), Japan (13%), Germany (9.1%), China (6.6%), Spain (5.5%), Italy (15.3%), United Kingdom (4.9%), Netherlands (3.9%), South Korea (2.4), Vietnam (2.3%) and other countries (13.7%), BFAR 2020 record shows. Many of such countries require imported fish and seafoods to be sustainably produced.

Addressing fisheries trends

When fish stocks became depleted in the 1990s in many of the country’s traditional fishing grounds due to overfishing, the Philippine national government enacted the Philippine Fisheries Code of 1998 and the Agriculture and Fisheries Modernization Act of 1997 that gave local government units authority to manage coastal resources.

These two laws were made to address fisheries trends, like the depletion of fish stocks, damage in marine and inland waters, and poverty among municipal fishers, among others.

The Philippines Fisheries Code clearly delineates the power of local government units (LGUs) in managing coastal resources. LGUs gained jurisdiction over municipal waters which are up to 15 km from the shoreline, and are mainly allocated for the municipal or sustenance small-scale fishers (using boats less than 3 gross tons).

Commercial fishers with boats more than three gross tons are by law required to fish beyond the 15 km municipal fishing ground.

In the 2000s, the Integrated Coastal Management approach gave a new direction in the management of Philippine fisheries by encouraging the participation of the community and other stakeholders, such as the local government units, donors, non-government organizations, academia, etc.

In 2010, there was a shift towards the ecosystem-based fishery management (EBFM) with the Republic Act 10654 of 2014 amending the Philippine Fisheries Code of 1998. The ecosystem approach to fishery management is an “integrated management approach across coastal and marine areas and their natural resources that promotes conservation and sustainable use of the whole ecosystem.” It seeks to keep a balance of ecological and human well-being priorities through effective fisheries governance (SEAFDEC), including the interests of artisanal fisheries and sustenance fishers.

In the case of Central Visayas region, the total catch of marine fish in its waters “peaked in 1991 and has steadily declined since then, clearly illustrating that the fish stocks have reached and gone beyond their sustainable fishing limits,” according to Green, et al, (2004).

Despite such a condition, the municipal and commercial fishers continued to intensify their fishing effort and acquired bigger boats, better equipment and technologies resulting in a situation where the fisheries ecosystem in the region all showed indicators of overfishing, the same study observed.

Tales of diminishing catch: from tuna to smaller fish

Loay, Bohol. Jesus Bensig, 53, captain of F/B Elzon City, a boat with 103 gross tonnage docked at Loay Port, some 18 km from capital Tagbilaran City, laments that he cannot possibly embark on a fishing operation given the windy weather that morning of June 29, 2022.

He instead tries to manage his men to fix the boat in preparation for a possible fishing trip when the weather gets better.

Bensig followed the footsteps of his father who was also captain of a fishing boat. He has been in the business for some 30 years. He started fishing at sea at 23.

In his view, there had been diminishing catch of big fish because there are too many fishers. Too many boats (at times, up to 20) with light which attract and scatter the fish, he says.

Small fishers are happy with 10 to 20 kilos of fish catch, but not the big commercial boats which need 10 to 20 coolers to break even. “Kami dili mahimo ug ginagmay nga kuha, kay daku mig gasto,” (We can’t afford to get a small catch because it costs a lot to go into this venture), he shares.

He uses 9-watt lights, he says, but if one wants to attract more fish, one uses superlight, which is prohibited. It is used in the open sea, adding that you’ll get warned if you use it in municipal waters.

He confides that there are areas in some municipal waters where they are “allowed” or “tolerated” to fish.

In his 30 years in the business, he observed the change in catch of species from tuna to the smaller ones, like burot-burot (mackerel scad) or tamarong (big-eyed scad). They seldom catch tulingan (frigate tuna), he says. When he started at 23 years old, all kinds of big fish were there, he notes.

The fishing boat has to contend with the wind and the current that affect the net, including the big marine mammals that follow the schools of fish which they feed on, he says.

The sonar fish finder in his boat has the sensitivity to detect the marks or shadow of the school of fish to as far as half a kilometer (5,000 meters) that he interprets and becomes the basis of his decision while at sea. “The decision is mine what action to take,” Bensig shares.

He acknowledges that he had been accosted for violating the allowed distance from the shoreline.

There are ordinances in Loay and Baclayon towns that prohibit commercial boat fishers from going too near the shore.

Small sustenance fishers: big fishing boats intrude in municipal waters

On the ground observations and experience of sustenance fishers in Bohol towns of Baclayon, Lila, Dauis and Jagna facing the Bohol Sea point to the disadvantaged situation of municipal fisher-folk who are no match to the well-funded and more technologically equipped commercial fishers.

The apparent continuous “sneaking” or intrusion by big fishing boats on municipal waters in Bohol has been seen by the small fishers interviewed as a major factor in their diminishing fish catch.

It is also viewed by a Bohol Fisheries official as a weakness in the enforcement of the law by local government units, which have been mandated to protect their municipal waters from big commercial fishers and the rights of subsistence fisher-folk in the area within the 15 km radius from the shoreline.

Banban, Lila

On a windy day in June, sustenance fishers of Lila town Philip Lagi and Edward Lagumbay, both 41, and three others, gather near the shore fixing part of a motorboat. Another one carves the wooden base (kasko) for a new pump boat, while others hang out near the beach where their boats are moored.

The sustenance fishers of Lila generally use the pukot (net) and hook and line in catching fish.

When asked what they observed of their fish catch: “Frankly, now it looks like fish are just passing through and are disappearing,” Lagi says, adding that the small fishers of Banban village are greatly affected by the big fishing operators.

“They (big fishers), with their big boats, are ‘sneaking’ into municipal waters. We see them fishing within 5 km from the shore. Nobody seems to care. We’re the ones affected,” Lagi shares.

He observes that the payao, a fish aggregating device used by big fishing boats, is a big factor in the disappearance of formerly abundant fishes in the area. The big fishers are not going to the high seas beyond the 15 km radius as stipulated by law, but are fishing on municipal waters, thus competing with sustenance fishers, the Banban village group concurs.

Lagumbay notes that the big fishing boats are equipped with fish finders which could easily detect the aggregation of fish. Once the school of fish is detected, the big fishers “just go under the payao, and confirm the school of fish (duot). Then they go around them with the ring net and sweep all the fish in the area, including the small ones,” he adds.

It would have been better, if they also have fish finders, Lagi comments, adding that while they have some local knowledge they learned from their folks about fish behavior, and signs and ways to detect the presence of “duot” (schools of fish), there is still a lot of guess work involved.

The small fishers spend from P200 to P350 ($3.57 to $6.25 at P56 to $1) for gasoline when they go fishing using their pump boat.

Lagi recalls that some 20 years ago, there were a lot of tuna fish, but since the appearance of commercial fishers, sometimes they could hardly break even, or at times, they have zero catch.

“During the tulingan (frigate tuna) season, sometimes we don’t find the tulingan. We suspect this is because the purse seine and ring nets take even the juvenile fish,” Lagi shares.

What is needed to improve the life of small fisher-folk?

“We believe that the law must be strengthened, or must be given teeth,” the Lila small fisher says.

When commercial fishers enter municipal waters, they are merely fined, Lagumbay observes, adding that what they pay as fine can be easily covered by their big catch.

Commercial fishers, he says, must be allowed to fish only after 15 km from the town’s coastline, that way they will not compete with municipal fishers.

“When they (big fishing boats) turn off their lights when fishing in municipal waters, they are trying to evade arrest. Now they don’t have to use much light. They have this waterproof torch light they drop underwater when they fish in municipal waters. If they are not accosted, pity the ordinary small fishers,” Lagumbay further says.

“When they drop their net and surround the payao, all the fish there are totally captured, which is not so in the case of the small fishers, who use the pukot, handline/fish hooks and spearguns,” he notes.

The biggest catch of a small fisher only amounts to 20 kilos or just one pail, while the big fishers get banye-banyera (vats), tone-tonelada (tons), up to 200 banyeras, he adds. Each vat loads 40 to 50 kilos.

They recall that there used to be fish sanctuaries in parts of Lila, such as Banban, Tokukan, Katugasan, etc., but they have not been operational for some time.

They hope for some action on their concerns of their being disadvantaged by big fishers.

“We are sharing our issues and concerns (mga yangogo) because we want these to reach the authorities concerned who are in a position to act on them,” Lagumbay reiterates.

History of local whaling and ray fishery

The coastal people living around the Bohol Sea have for centuries adapted in unique ways to the particular marine environment which is frequented by large marine vertebrates.

Local whaling had been practiced by a small community in Lila town and in Pamilacan Island in Northern Bohol Sea for over a century, according to Jo Marie Acebes (2013).

Stories of the complex interaction between some coastal area population of Lila, Jagna and Baclayon towns and their marine environment can still be heard to this day through the sea hunters of Bohol.

Accounts of Pamilacan Island’s former whale hunters and Bunga Mar, Jagna’s ray hunters, show unique implements and techniques used by the coastal villages of Bohol to hunt their prey.

In these villages, there were hunters for “bongkaras” or Bryde’s whale and manta rays. They were known to jump from the bow of a wooden boat to the whale’s or manta ray’s back carrying a giant iron hook called “pamilak” which they attach with a rope on the giant marine mammals.

A second and third boat would again hook the whale which has been tied to a bamboo raft/floater until the prey gets tired. It took hours to subdue a whale, witnesses in Pamilacan Island said.

The whole community engaged in the cutting up of the whale whose meat was a valuable source of high protein which could feed the entire village for a month (National Museum Bohol).

“By the late 20th century, with increasing population, worsening economic conditions, and declining fish stocks in the country, the Bohol Sea fishing communities’ dependence on fisheries for large marine vertebrates also increased,” Acebes (2013) wrote.

All species of whales were protected in the Philippines in 1997, and whale hunting had been banned. However, ray fishery continued, but was ended in the late 2000s.

Coastal communities then continued with sustenance artisanal fishery, but some became part of tourism activities, like dolphin watching and sanctuary tours, and lately, whale shark watching.

Whale shark interaction

In Taug, Lila, some 28 km from Tagbilaran, there is a “Whale Shark Watching and Snorkeling” tourism venture that make tourists come out and paddle boats, then snorkel and scuba-dive with the marine mammals.

When photos appeared on social media showing tourists feeding the whale sharks in 2019, several environmental groups appealed to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Office (DENR), BFAR, and the provincial and local government concerned to stop or prohibit whale shark feeding in the area, and instead promote sustainable tourism.

With 6 to 13 whale sharks in the water off Lila, tourists are still invited or encouraged to visit the coastal village of Taug to “interact” with the sea creatures. Foreign tourists pay P1,200 ($21.43) per person, while visiting Filipinos pay P700 ($12.5) per person (as of May, 2022).

Local paddlers accompany at least 10 tourists at a time on a boat and swim around the designated “interaction” area, some 30 meters from the shoreline. The “interaction” takes some 30 minutes.

One of the tour operators denied that the activity with the whale sharks involved feeding the marine mammals, adding that it is simply whale shark watching and snorkelling. “The whales are free to go and to hunt for food,” he was quoted to have said by local media.

The small fishers of Banban, Lila, however, questioned the feeding of the whale sharks in their town with krills for tourism purposes. “Now there are whale sharks that are just hanging around (in Laug village) waiting to be fed,” Lagi said.

Ever since the hunting of whales and manta rays was stopped, the anchovies and krills have also become fewer since the whale sharks are now competing with humans in catching the small fish, he observed, adding that “they (the sharks) have no more predators.”

In an open letter to government agencies, the Free the Whale Sharks Coalition—Bohol (FWSB) called for an end to the feeding of the whale sharks in Lila or anywhere, saying that the practice would also diminish the marine mammal’s ability to hunt, and would even put them at risk of getting hurt.

Taming them by feeding will make the wild animals lose its natural instinct to live and hunt, and luring the animals could make them dependent and susceptible to injuries, and even poaching.

A position paper by the Save Sharks Network Philippines said that monitoring by satellite tagging of whale sharks in Donsol, Sorsogon, and Sulu Sea showed that “whale sharks spend more time in deep waters, with the area of the deepest dives at over 1,400 m recorded in the Bohol Sea.”

If the marine vertebrates “do not migrate to their deep habitats or the next feeding area, which are possibly mating and spawning grounds, they will be unable to perform their ecological roles in these ecosystems,” it added. It concluded that as “endangered species…they need all the reproductive opportunities they can get.”

The Federation of Fishermen Association of Baclayon recently (February 21, 2022) requested in a letter to the Bohol Provincial Council’s environment and tourism committees to allow its members to feed whale sharks, locally called ‘butanding”, in their area, for at least 3 to 4 hours per day, for tourism business purposes.

The request was made “for the benefit of the livelihood of about 200 fisherfolk members of the association in Baclayon town who want to operate a whale-watching business in their area,” the letter says. The committee refused to amend the provision of a provincial ordinance that prohibits the feeding of whale sharks in the province.

The story was produced with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network’s Ocean Media Initiative 2022.