MALAYBALAY CITY (MindaNews) — In a corner at the local crafts store, 38-year old Marj Libanda, father of two, strings beads into a headdress to meet a local order. He has been at this for a couple of weeks even as some say this is not a man’s job.

Libanda used to be a security guard for a poultry farm and had earlier worked as farm laborer, vendor and construction worker.

In the handicrafts store of Perla Rubio, an exporter of fashion accessories, Libanda earns an average of 200 pesos a day based on the number of pieces he finishes. A friend has enticed him to work in a construction project where the pay is higher but there is no vacancy for now. Back in Manalog, an upland village here, neighbors earn a living as farmers of abaca and weavers of its textile product.

Marj Libanda, strings beads into a headdress in the store of an exporter of handicrafts made of abaca and other indigenous materials in Malaybalay City, Bukidnon. (MindaNews photo by Walter I. Balane)

His mother is among the village’s long time weavers. But they are experiencing a slowdown of production of due to a number of problems, including diseases plaguing abaca hills and lack of access to financing to buy weaving machines.

Rubio, his employer, says business is picking up but notes that while local crafts may be able to compete in the domestic and international markets, cost issues are a problem.

National government agencies like the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) and the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) have provided Rubio support but she is not getting any help from agencies nearer her.

“There is no support from the local government. We don’t see them backing us,” she said.

For Rubio, local government units (LGUs) must support small and medium enterprises in their area, especially in helping them access enterprise development and business opportunities.

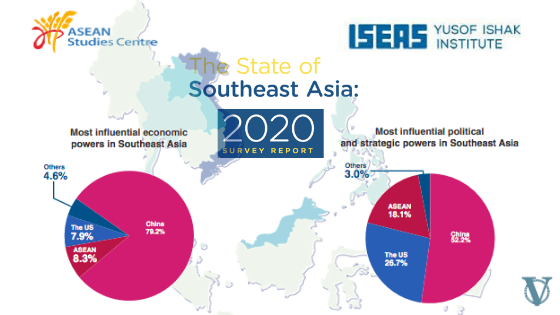

Rubio said she has been wanting to join a trade fair in Malaysia, hoping to tap the market in the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN). But getting there is a problem due to transportation and other costs.

BIMP-EAGA Forum

Romeo Montenegro, Mindanao Development Authority Assistant Secretary told MindaNews LGUs play a critical role in realizing many of the targets under ASEAN integration. He cited the effort to generate wider public engagement across political, economic and socio-cultural pillars.

The Brunei -Indonesia-Malaysia-Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA) LGU Forum (LGF), he added, has been adopted as a regular venue for local governments of the focus areas to convene, exchange ideas and pursue possible collaboration to complement specific projects of different clusters. So far, the BIMP EAGA has five pillars: connectivity, food basket, tourism, environment and socio-cultural.

But he admitted that the forum is convened only if there is a meeting of the ministers. When there is none, they don’t see each other.

In the BIMP-EAGA Vision (BEV) 2025, the new blueprint for development in the sub-region, the LGF is considered an institutional mechanism. Started in 2004-2005, the forum is made of the chief ministers of Sabah and Sarawak and the chairman of the Labuan Corporation in Malaysia, and governors of the provinces of Indonesia and the Philippines; Brunei Darussalam is represented by its Ministry of Home Affairs.

Much remains to be done about the forum, which is supposed to promote cooperative activities and opportunities for cross-border trade and investment on a bilateral or multilateral basis.

Interestingly, while the 12th BIMP-EAGA Summit identified “increasing local government engagement” as one of four aims, only one of the 22-item joint statements at the end of the summit in Manila last April mentioned local government.

“We urge our respective concerned agencies at the national and local levels to provide policy, technical, funding and administrative support to ensure the effective, efficient and timely delivery of the BEV 2025,” it said.

Montenegro attributed this to the lack of multilateral framework on how LGUs can participate directly.

“There is no functional mechanism yet that the LGF can operate on its own. This is something we will still have to build,” he added.

Residents of Manalog in the hiterlands of Malaybalay City in Bukidnon need a bamboo raft to cross a river to get to reach the village. Manalog is home to weavers of hinabol. (MindaNews photo by Walter I. Balane)

On the side of the Philippines, he said, they are looking at establishing first the Mindanao-wide framework.

“We are not looking at Davao and General Santos cities only, we will factor in the other LGUs,” he added.

Montenegro said so far there are only bilateral frameworks between Davao and Manado (Indonesia) cities and Palawan and Kudat (Malaysia) primarily because of the direct connectivity, specifically commercial flights, already established in the past.

He admitted, too, that initial feats in engaging the LGUs are limited only to the key cities like Davao and General Santos. Nothing has been substantially done for interior provinces, like Bukidnon.

Jezreel Mangubat, Acting Provincial Planning and Development Officer of Bukidnon, one of Mindanao’s 27 provinces, said there is no direct engagement in activities as yet between the province and the movers behind BIMP-EAGA mechanisms.

“It’s just indirect. Our only possible connection is our alignment to the Philippine Development Plan (PDP). We have to align our plan to the PDP,” he said.

Mangubat said he looked forward to capacity development opportunities so LGUs can be more mindful of working towards the direction of BIMP-EAGA.

Local planners admit that the private sector in the locality have been directly involved through their business chamber and DTI.

Mainstreaming BIMP-EAGA

Roleyne Florendo, in-charge of the Bukidnon Investment and Export Promotion Office, said in the last five years that they have not been involved in any forum organized to mainstream the BIMP-EAGA among the LGUs.

In 2015, DTI-Southern Mindanao invited the province for the setting up of the BIMP-EAGA (Philippines) Trade, Tourism and Investment Promotion Center. But it was only so they can invite producers or micro small and medium enterprises to display in that center.

Mangubat said it is important to include all LGUs in Mindanao not just the cities of Davao and General Santos and the provinces of South Cotabato and Sarangani.

“One advantage if LGUs are included in the circulation is they can factor in opportunities in BIMP-EAGA in local planning mechanisms, like the local Commodity Investment Plan,” he added. The CIP is an expression of the LGU’s use of local resources to develop priority commodities like coffee, mango, coconut coir and even Abaca.

Mangubat said provinces have vast potential of participation in regional integration through trade, tourism and agriculture-related industries.

“That is if LGUs in the periphery (like Bukidnon) are directly involved,” he added.

Where is mainstreaming?

Increasing local government engagement is one of the goals of the ASEAN integration, specifically in the BIMP-EAGA. But local governments outside of the key areas are not directly engaged.

Mangubat said this is unfortunate because provinces like Bukidnon have vast potential of participation in regional integration through trade, tourism and agriculture-related industries.

Montenegro told MindaNews ASEAN integration offers LGUs a chance to promote themselves and improve their competitiveness as they set sights on a larger market for their products.

But he said given the varying capacities of LGUs, the challenge is that some may be left behind if not assisted.

“Local officials have to ensure that their areas are competitive enough to fully take advantage of the opportunities of economic integration,” he added.

This is where national government offices, like the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG), need to pursue efforts to mainstream LGUs, he added.

“More concretely in assisting them put together programs and projects that make them direct participants to cross-border socio-cultural and economic interchange,” he added.

DILG Undersecretary Austere Panadero said LGUs need to be equipped with the right knowledge and instill in them the value of being part of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), as quoted in the DILG website. He said during the “Forum on ASEAN Economic Integration: The Role of Local Governments” that there is a need to streamline the roles of all who are involved in the process to enhance capacities to support local and small and medium enterprises.

But Bruce Augusto Colao, then provincial director of DILG-Bukidnon said in na interview on September 4 that mainstreaming is yet to reach the provincial level.

Undersecretary Zenaida Cuison-Maglaya of the Department of Trade and Industry said in a decentralization forum in 2015 that the national government is dependent on local government units to provide better support for small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

OTOP needs attention

Abaca-based handicrafts have been identified as the focus in the one-town one-product (OTOP) of Malaybalay City, the capital of Bukidnon, the only major producer of abaca in Northern Mindanao.

Under President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (2001 to 2010), the government developed OTOP to promote goods and products of Filipino towns, cities, and regions, and provided funding for small businesses. The project was expected to end in 2010, but the Aquino administration continued it.

Workers extract fiber from the leaf sheath around the trunk of an abaca plant in the hinterlands of Manalog in Malaybalay City, Bukidnon. (MindaNews photo by Walter I. Balane)

Under President Rodrigo Duterte, OTOP continues as “OTOP Next Gen.” But according to DTI, it focuses on scaling up micro, small and medium enterprises in terms of branding and marketing.

According to the Philippine Fiber Industry Development Authority (PhilFIDA), export earnings from abaca products went up 17 percent in the first 10 months of 2016 despite a slight decrease in volume demand from major markets.

Abaca export sales reached $113.5 million from January to October last year compared to $97 million in the same period in 2015, according to a philstar.com report.

Abaca pulp accounted for $78.5 million of total exports, up 18 percent year on year.

Shipments to Europe fell three percent to 13,721.8 metric tons (MT), while shipment volume to Asia declined 13 percent to 3,181.3 MT. The US purchased 2,338 MT or nearly double last year’s level.

But timely interventions have to be undertaken for the fiber industry in the province if it is to sustain its niche in the region, according to the Regional Abaca Industry Background.

Bukidnon’s average yield is comparatively lower than other major abaca producing provinces such as Catanduanes and Surigao del Sur.

“It is therefore important that areas of abaca plantation that need rehabilitation and expansion be provided with access to high yielding varieties and disease and pest resistant varieties,” according to the primer. The PhilFIDA and the Provincial Government of Bukidnon have to consider this intervention as part of the investments that have to be pursued.

Accordingly, better farm to market roads is important in having an enabling environment.

Mangubat said the provincial government has included abaca in its Commodity Investment Plan in terms of farm to market roads, thanks to the World Bank-funded Philippine Rural Development Project (PDRP). He said cooperatives and other people’s organizations may propose financing plans but there were only proposals for coffee and cacao.

For abaca, he said farmers and weavers may apply for the provincial government’s livelihood projects, under Economic Services program, one of its seven pillars of governance.

But there is more to what ails the abaca industry.

Genevieve Labadan, enterprise development officer of the Non-Timber Forest Products –Task Force (NTFPTF), which operates a network of abaca textile weavers in the Philippines, Cambodia, Indonesia and Malaysia, said the core issue for them as of now is the quality of their product.

“We can catch up with quantity and talent but not yet ready quality-wise,” she said in a telephone interview.

In 2011, the group was able to organize 100 women weavers from six barangays, including Manalog, for the mass production of naturally dyed abaca cloth or hinabolfor export to a United States-based firm. They produced a total of 14,004 meters of hinabol and shipped 4,277 to the US. The rest were absorbed by a local center for value addition, according to Not By Timber Alone newsletter in 2012.

Labadan said they had to stop taking orders pending standardization.

Groups of weavers in Manalog and two other villages in Impasug-ong town are now applying standards set through their project Good Hinabi Practices (GHP) to make sure they can stand out in the international market.

“We are specifically aiming at becoming ASEAN Economic Community ready,” she added.

NTFP-TF, she said, works with national agencies but they have already started working with LGUs at the ground level to seek their support in promoting the standards.

Junar Merla, a senior development specialist of DTI-Bukidnon said the city of Malaybalay, too, provided support for plant materials and training for the abaca growers. LGUs should engage in product development and promotion of abaca products because they have more resources, he said.

In Libanda’s village in Manalog, there are two sets of abaca textile weavers: one organized by a non-government organization, NTFP-TF, which coordinates with national and local agencies to help local crafts gain access to the international market, and the other, which comprises the majority — unorganized local weavers who are home-based and have no access to financing or other support.

The same is true with abaca farmers.

It was the military that set up the 40-member Manalog Abaca Planters Association after a recent encounter with the rebels in the area. But the group said they have to address disease plaguing the plants. They need technical assistance, aside from seeds and fertilizer.

The group also sought help to buy a machine used to extract hemp. But Lerio Libanda, head of the newly formed group said they hope to get support from the local government and other agencies even if there is no trouble.

“We need it to earn a living here,” he added

What ails localization?

Labadan, a community organizer who worked with weavers in abaca-producing communities believes the primary problem of the weaving industry is quality and standardization

“We are looking at an internationally competitive weaving industry,” she said.

Labadan said the women’s groups they organized in Manalog in upland Malaybalay City and two other villages in a nearby town are applying Good Hinabi Practices (GHP) to make sure they can stand out in the export industry.

She noted that while the NTFP-TF works with national government agencies, they have yet to work extensively with LGUs.

“LGUs should also be culturally sensitive as they cannot impose to weaving communities work structures that serve only their purpose,” she said.

Labadan said local governments should pitch help so weavers can access financing and promote their products.

“We need the help of the local government. At the least, we need them to create local policies that adopt the standards for quality,” she added.

Mangubat said when they considered abaca in Bukidnon’s Provincial Commodity Investment Plan (PCIP), they factored in support in its value chain – production, marketing and other enabling mechanisms. Mangubat, however, could not specify how much crop support abaca is getting so far.

Difficult

The mechanism of engaging the LGUs in the integration is not always easy to manage noting the difference in each country’s political set-up, said Montenegro.

Indonesia and Philippines may have parallel LGUs through provincial governors but Brunei has no LGUs, only central and absolute monarchy while Malaysia is broken down to federal states led by chief ministers.

In the Philippines, among the main responsibilities of MinDA as the national secretariat, is to ensure appropriate representation and active participation of both national and local stakeholders in sub-regional cooperation activities.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) in 2013 said local government participation is “slowly but progressively being addressed” through the LGF and existing working groups in the countries.

“However, there are weaknesses in these mechanisms that have constrained the participation of local governments and more efforts are needed to enable them to play a larger role in the BIMP EAGA activities,” the ADB said in the publication “Regional and Subregional Program Links, Mapping the Links Between ASEAN and the GMS, BIMP-EAGA, and IMT-GT”.

The ADB found out in its review that the current sub-regional institutional frameworks and mechanisms were effective only as far as consultations and dialogue among member countries are concerned. The structures and mechanisms, however, are not ideal for the implementation and monitoring of the progress of identified flagship and priority projects.

In Mindanao, a question that has often been asked is how much decentralization is happening between the national and the local governments?

Bronx Hebrona, who represents the private sector and sits as chair of the sub-committee on ASEAN and BIMP-EAGA of Region 12’s Regional Development Council said one problem in the Philippines is cascading national policies to the local level.

“The local is not harmonized with the national. Sometimes what’s painted as nice picture on international trading in the national scene is a different situation on the ground,” he added.

Montenegro said the Duterte Administration has considered the BIMP EAGA as one of his major agenda of discussion with heads of states of the involved countries.

Duterte rallied ASEAN to focus its attention to the development of sub-regional economic cooperation as a mechanism to fast-track the realization of ASEAN goals and objectives, he added.

He said the administration viewed the BIMP-EAGA as leveraging factor in the national government’s peace-building efforts in Mindanao.

The various infrastructure projects like roads and ports development the current administration is pouring in Mindanao directly support its trade facilitation and promotion in BIMP EAGA.

Montenegro added that the inclusion of BIMP-EAGA among the national priorities shows President Duterte’s push to develop all regions and that Mindanao’s development is his foremost priority.

“Local communities of Mindanao should be prepared to accept investment influx and other economic partnerships with neighboring BIMP-EAGA and ASEAN countries while managing sustainably its own resources, capacities, and strengths as an island-region,” he said.

But he stressed that the long-term initiatives should be assisted by an enabling environment like in-place investment areas, balanced ecosystem and preserved cultural heritage, and stable peace and security atmosphere.

“We are looking at putting up BIMP-EAGA desks in the provinces to help promote more participation,” he added.

Mangubat said the provincial government has set up the Bukidnon Investment and Export Promotion Office in 2011. This is to increase effort to take advantage of opportunities in the BIMP EAGA, he added.

But he said they need more access to opportunities to be directly involved.

For weavers like 38-year old Arcily Lucid in Manalog, they don’t know what “ASEAN” or “BIMP-EAGA” stands for.

“Whatever they are, hopefully they can help make keep demand for our hinabolcloth,” she added.

Hinabol weaver Arcily Lucid explains how she manages to complete eight meters of abaca cloth a day in her workshop at her family’s ancestral house in Manalog, Malaybalay City, Bukidnon. (MindaNews photo by Walter I. Balane)

The mother of four finishes an average of eight meters of woven abaca per day. She said hopefully, the price per meter of P60 to P70 back in April 2017 would also increase.

“It should pay better for us,” said Lucid, who learned the craft early from her mother and grandmothers.

Libanda and his neighbors in Manalog, one of Bukidnon’s 464 villages, said it all boils down to having food on their table.

As he accompanied this reporter to visit the village on a rented motorcyle, he said: “more or less it’s the same village and the same me all the time.”

“I hope I don’t need to leave town again. I know we will always come home here. Abaca is our asset,” he said. (Walter I. Balane/MindaNews)

(This story was produced under the Reporting ASEAN program and media series implemented by Probe Media Foundation, supported by an ASEAN-Canada project, funded by the Government of Canada. It is also in partnership with AirAsia, and in collaboration with the ASEAN Foundation. Walter Balane is former Bukidnon and Davao reporter of MindaNews and is now journalism and development communication educator of Bukidnon State University. He is one of the ten Reporting ASEAN fellows in 2017.)