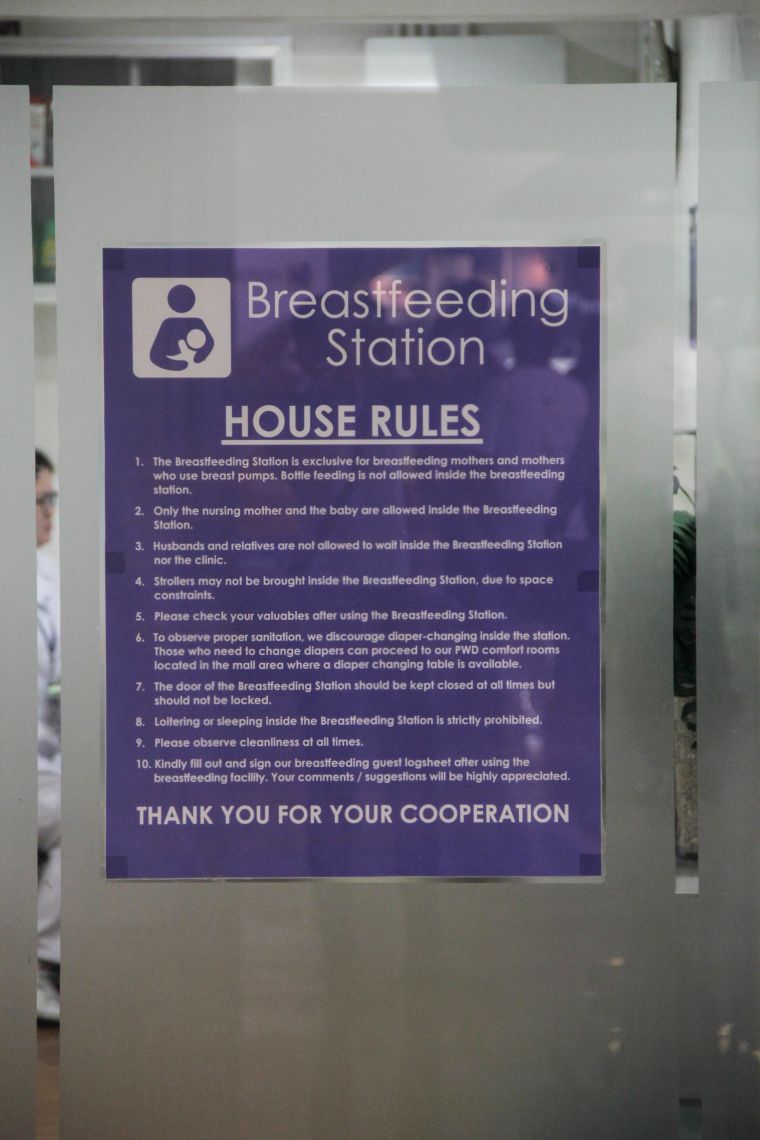

Lunchtime is always busy at the food court of the country’s biggest mall. As shoppers make their way to fast-food stalls and restaurants, it is almost easy to overlook the small, blue sign atop the single glass door in the corner.

The door leads to a room where babies have their own version of a meal while cradled carefully in their mother’s arms.

Second-time mom, Christina Matulac, 30, who opted to try purely breastfeeding for the first time, said such stations serve as a comfortable space for nurturing mothers like her to do their business while in a public place.

“Mas convenient, kumportable siya kapag nasa labas, kahit na may cover, kasi puro breastfeeding moms kayong nandoon (It’s more comfortable when you’re out of the house, even if you have something to cover it up, because you are all nurturing mothers inside),” she said.

The stations also make it easier for the baby to feed, first-time mom, Maricel Villegas, 23, shared.

“Kumportable yung bata kasi talagang nabubusog [siya] kapag pumapasok kami sa breastfeeding section (The baby is more comfortable when I feed her inside the station),” she said.

Matulac and Villegas can thank the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and SM Supermalls for providing breastfeeding stations for their customers. They built the first of its kind in Megamall way back in 2005.

At the time, UNICEF noted that only four out of 10 Filipino children have received the benefits of breastmilk–a troubling result considering that breastfeeding is important in reducing child mortality and improving maternal health.

Twelve years later, SM President Anna Garcia said the partnership has already served almost half a million nursing mothers and will be launching their 62nd breastfeeding station in Puerto Princesa in Palawan in September.

“By offering breastfeeding stations in our malls, we believe that we support the continued breastfeeding lifestyle of mothers even outside their homes,” Garcia said.

Building breastfeeding stations is just the beginning; with the launch of Children’s Rights and Business Principles (CRBP), a set of guidelines for the private sector, UNICEF hopes to encourage more companies to do their share in upholding children’s rights.

“There are at least 33 million children in the Philippines. They buy your products, they are part of your services, they watch your shows, they see your TV ads, they use your online platforms, and they are children of your employees,” UNICEF Philippine Representative Lotta Sylwander told business executives during the launch of the CRBP, June 14 in Makati City.

It is for this, and a number of other reasons, that the CRBP initiative was brought to the country, she said.

According to the guidelines, businesses must “ensure the protection and safety of children in all business activities and facilities,” as well as guarantee that the products and services they provide are safe for children’s use.

Businesses must also make sure that their marketing and advertising materials follow the CRBP’s guidelines.

In Thailand, one of the biggest real estate developers supported a major public campaign to prevent iodine deficiency disorders among children. Iodine is an essential nutrient for brain development that can increase a child’s intelligence quotient up to 15 points.

This initiative eventually pushed the Thai Ministry of Public Health to adopt regulations on mandatory iodization.

A similar initiative was started in the Philippines, again with SM, in assessing the quality of iodized salt sold in its supermarkets. As a result, all salt vendors of its supermarket group are now required to submit a quarterly certificate of analysis indicating the desired level of iodization prescribed by the Food and Drug Administration.

But despite these successes, UNICEF recognized that there is still much to be done, particularly in encouraging those with lesser resources to join the cause.

“The reason the UNICEF in the Philippines and in other countries is looking to slightly larger companies is because they have a little more space to actually start doing these kinds of changes,” UNICEF Regional Representative for Asia, Erik Nyman, said.

Another advantage for large companies is their link to key drivers such as more customers, investors and international supply chains, he added.

That being said, small and medium enterprises with a broader supply chain dynamic might still be able to do such, but in a “more basic level,” Nyman said.

Of the 900,914 establishments in the country, about 99.5 percent, or 896,839 of them are classified as micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs), according to 2015 data of the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA).

MSMEs are business enterprises with an asset of P100 million below and less than 200 employees.

A smaller scope might also work to the business’ advantage, Nyman said.

“A lot of small, medium enterprises are already doing a lot better systematically because they are small; they know their employees, they are more dependent on [them] too, so they see the children, ” he said.

An example of this is a coalition of small and medium enterprises in Thailand that works to get the migrant employees’ children into education, Nyman shared.

But while reaching out to MSMEs pose a challenge, addressing children’s issues in the informal sectors are even more difficult.

Child labor remains to be the most urgent issue faced by the informal sector, according to Sylwander. However, UNICEF has yet to draft specific courses of action to address this.

The informal sector refers to employment and production in unincorporated or unregistered enterprises.

“It is usually in the informal sector where children are working, and we need to raise awareness [on] what it does to a child who is working instead of going to school or playing,” she said.

In 2011, around 7.9 percent, or 2.1 million out of 26.6 million children in the country, ages 5 to 17 years old, were said to have engaged in child labor, according to PSA.

Republic Act. No. 9231, or the Anti-Child Labor Law, defines child labor as children below 15 years of age who are involved in work that “endangers his/her life, safety, health and morals” or “impairs his/her normal development.”

More than half, or 53.2 percent of the working children were 15 to 17 years old, 38 percent were in the ages of 10 to 14, while those who were 5 to 9 years old accounted for 8.8 percent.

Most children, about 58.4 percent, are in the agricultural sector which is found in the rural areas. Those engaged in service-providing establishments account for 34.6 percent, while the industry sector employs about 7 percent of the working children.

The author is a University of the Philippines student writing for VERA Files as part of her internship.