The Philippines’ school system, both public and private, had to shift to online classes due to the lockdown imposed due to COVID-19.

It’s too early to assess how effective online classes are compared to the face-to-face classroom setup. But teachers and parents say the online classes are full of challenges. The following article by Yap Kai Ling for Reporting Asian shows that the Philippines is not alone in having difficulty with virtual classes.

Malaysian Maxwell Leo Lee

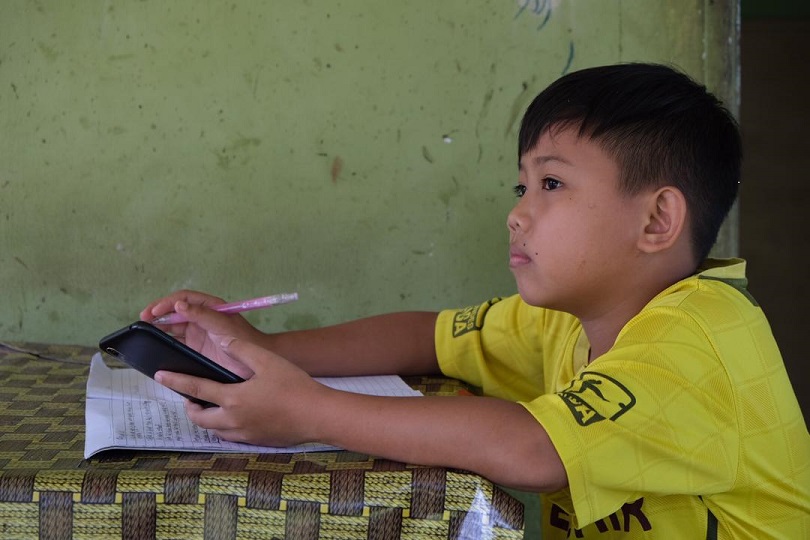

KOTA KINABALU, Malaysia – Maxwell Leo Lee’s ‘blackboard’ is his smartphone, which is just a little bigger than his hand. The 11-year-old Malaysian student has been doing e-learning since March, when the government suspended physical classes in schools across the country amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

But home-based e-learning is often ‘slow’ learning, given the challenges of getting a stable-enough internet and data connection from Maxwell’s home in Pinopok village, Membakut subdistrict of the eastern province of Sabah.

The indicator on his phone usually ranges from ‘Emergency calls only’ to two bars of 3G. However, internet connection reaches a full five bars for residents of the same subdistrict who reside in town, some eight kilometres away.

“The internet connection in the front porch outside of our house is not stable,” says Maxwell’s mother Rina, a rubber tapper. A single mother, she has her hands full looking after her son and a sickly older daughter, her elderly parents who live with them. Her third child, her eldest daughter, passed away in 2019.

“To get the best connection, we go up that hill to download the notes,” she said, pointing to her right. “But when it rains, we cannot go out, so we have to bear with what we can get.”

Maxwell’s lessons and homework come through the WhatsApp group chat of his school’s parent-teacher association. The Grade 5 student is taking six subjects at the Tamalang National School, just a 1.3 km walk from his home.

When Maxwell does not fully understand the subject notes or homework instructions, Rina sits down with him. “E-learning requires us parents to be more involved in our children’s studies. When he struggles with his homework, I will have to teach him,” she said.

At times, his grandfather helps ensure that Maxwell finishes his homework, which is due for submission within the same day.

But the first basic tool for education in these pandemic times is internet connectivity. Despite its 83% internet penetration rate and its being among the most developed countries in Southeast Asia, Malaysia still has a digital divide, as Maxwell’s situation shows. It has been posing a major challenge in the country’s efforts to ensure that education continues during the pandemic.

The average speed of mobile internet connections in Malaysia is 23.80mbps, according to the ‘Digital 2020 Reports’ published by We Are Social and Hootsuite.

While 4G coverage is more widely available across the districts in the country’s west, which includes the capital Kuala Lumpur, it is a different story in other areas.

An October 2019 report by the mobile analytics firm Opensignal, in fact, finds that Malaysian users in lower-density rural communities of less than 10 people per square kilometre are able to connect to 4G only 44% of the time. But in cities with more than 300 people per sq km, this goes up to 83.7%.

More sparsely populated areas, such as those in Sabah and Sarawak states in East Malaysia, experience the lowest 4G connection availability, it found.“Those districts have a higher proportion of rural areas, where operators usually find it more challenging to deploy and maintain the required network infrastructure,” the Opensignal report stated.

Maxwell and his mom

The disparity in gaps in quality also exists within states, with connections usually poorer in more remote and rural areas, such as Maxwell’s community in Sabah.

For instance, good 4G connection – which does not get disrupted during heavy rains – is widely available in the Sabahan capital of Kota Kinabalu, some 90 kilometres away from where Maxwell and his family live.

Aware the access to the internet fluctuates, Maxwell’s teachers have at times sent notes over as pre-recorded video clips. They often avoid holding live video classes, which require better internet connection.

The impact of the digital divide on home-based learning has also been highlighted by the viral story of 18-year-old Veveonah Mosibin, who posted a video clip of herself spending the night on a tree to get better internet connection ahead of her online examinations. As of late September, her YouTube clip has gotten more than 840,000 views.

The story of Veveonah, a science student at the University of Malaysia Sabah (UMS) public university in Kota Kinabalu, is not very different. She lives in Sapatalang village in the Pitas district of Kudat, some 168 km away from the city. Veveonah, too, heads for higher ground to catch a better internet connection.

“Moving towards the Fourth Industrial Revolution (the use of smart technology), the university has always emphasized e-learning, but it was just an alternative that was encouraged to be used before,” said Lee Kuok Tiung, a communications professor at UMS.“(But) now, it’s almost compulsory because we cannot have face-to-face classes or meetings,” he added.

He uses WhatsApp, the most widely used messaging application in Malaysia, to contact his students. “The internet has become the main platform or medium for teaching and learning. Even exams are online,” he remarked. But he added, “the internet line is still very much lagging behind”.

There is good news for Veveonah, whose community should have a new telecommunication tower for 4G connections in 2021, according to the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission. The current tower only handles 3G.

“In Sabah and Sarawak, we may not have the population and market (size) like in Peninsular Malaysia. But we deserve the same quality of service, as we are paying the same amount of money based on the package that we subscribe to with the telecommunication company,” Lee asserted.

Community efforts, such as those by activists like Angie Chin-Tan, have emerged to help students and teachers in rural Sabah get access to online devices for educational purposes during the pandemic. Apart from struggling with internet quality, residents often have old devices, lack suitable ones, and cannot afford proper ones.

A crowdfunding platform called HanaFundMe, started by Chin-Tan, has distributed 25 devices to village students as of late September. It has gotten support from telecommunication providers Huawei and UMobile for devices and SIM cards.

In cities, students can afford a mobile phone, laptop or personal computer for home based e-learning, Chin-Tan says. But in rural areas, students have had to borrow devices from parents, relatives or friends.

“Almost everyone was caught off guard and were unprepared when the COVID-19 pandemic hit us,” said Chin-Tan. She adds that the government should roll out new ways of learning, making sure that “no children are left behind in their studies”.