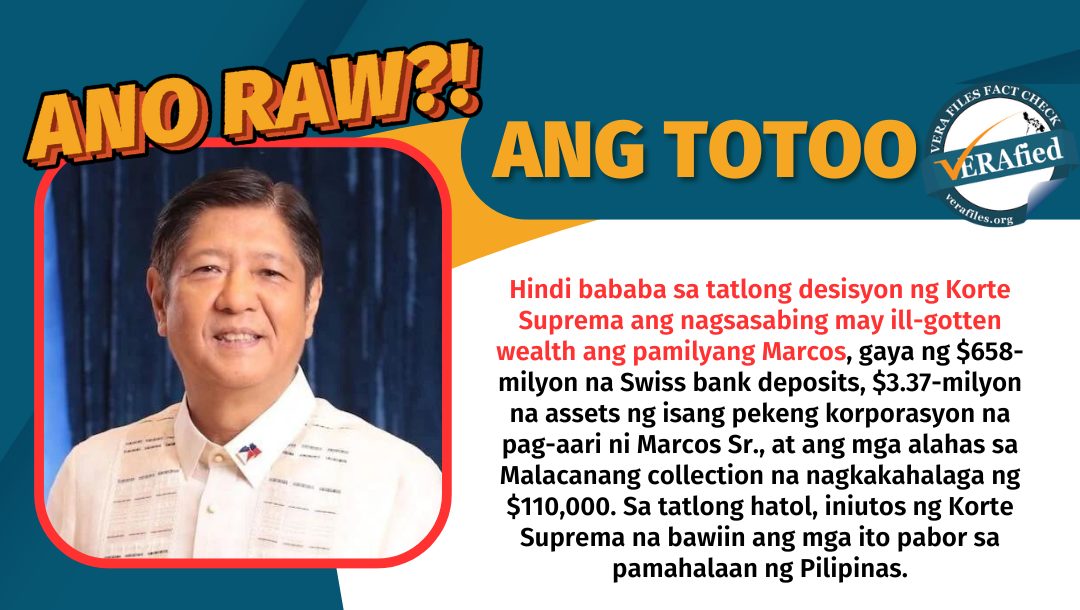

A whole book, Marcos Lies, has already been written documenting in copious detail the Marcoses’ penchant for making untrue statements mythologizing themselves. But at least one Marcos, the president himself, Ferdinand “Bongbong” R. Marcos Jr., is still constantly giving material for future volumes, undermining his own administration’s anti-misinformation drive.

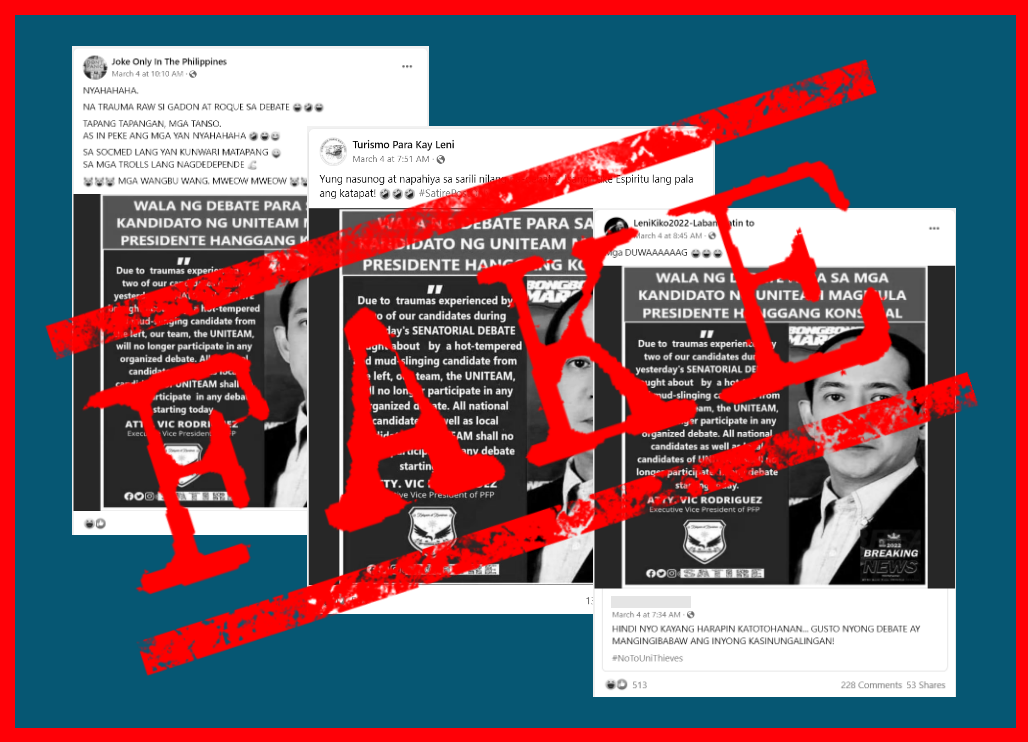

Many of these false statements are being circulated—in the form of press releases, transcripts, and audiovisual recordings—by offices under the Presidential Communications Office (PCO). On August 14, 2023, the Marcos Jr. administration launched a Media and Information Literacy Campaign, popularly billed as the government’s anti-fake news initiative. The PCO is the lead agency of the campaign. At launch, some found the campaign to be, at the very least, tinged with irony, given various evidence-based claims that Marcos partly relied on massive disinformation during his presidential run. During the recent 2024 budget deliberations in Congress, the PCO, based on its own reportage, “earned the approval and support of the House of Representatives on its Media and Information Literacy (MIL) campaign,” after proposing the allocation of ₱16.899 million for the program. Will some of that money go to correcting false or inaccurate statements even if they are made by the president himself, or help in further propagating them?

Rice price

An October 7, 2023 news release from the PCO bore the headline: “Price Cap Stabilized Rice Prices – PBBM.” The article does not explain how the president, concurrently secretary of agriculture, determined that the price ceilings he set on regular millied and well-milled rice (via Executive Order no. 39, issued on Aug. 31, 2023, which took effect on Sept. 5, 2023) directly led to rice price stabilization. The order lifting the price cap, Executive Order no. 42, issued on Oct. 4, 2023, simply states that the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Trade and Industry “have jointly recommended the lifting of the mandated price ceilings in view of the decreasing rice prices in the domestic market, increasing supply of rice stock, and declining global rice prices”; again, no causal relationship between the price cap and price stabilization is established. Critics have pointed out that rice prices have in fact been increasing, and is the main driver of recent food inflation; indeed, the Philippine Statistics Authority stated that the “uptrend in the food inflation [in September 2023] was mainly due to the higher annual increment in rice with inflation rate of 19.8 percent during the month from 9.1 percent in the previous month.”

In March this year, rice industry monitor Bantay Bigas also called out the president for stating that his promise of lowering the price of rice to 20 pesos per kilo was close to becoming a reality (“Kaunti na lang, maibababa na natin ‘yan,” were his exact words). Clearly, rice prices are still nowhere near 20 pesos per kilo. That for months now, Marcos has seemed unable to be truthful about the price of rice should not be surprising to those who know the various falsities that he has propagated both about himself and his family, ranging from false claims about his educational attainment to characterizations of his father’s dictatorship. Well into the second year of the Marcos Jr. administration, dishonesty still readily attaches to the Marcos name.

Relocated birthplace

Some recent false information circulating about Marcos may be in the nature of clerical errors. For instance, in his official website, pbbm.com.ph, the president’s biography states that he was born “in the town of Batac, Ilocos Norte.” Marcos was born at Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital in Santa Ana, Manila. He did not even grow up in Ilocos Norte (by his own admission, he can hardly be considered fluent in Ilocano), though he had to claim residency there during the times that he was either an elected executive (with a reputation for being an absentee governor) or a congressional representative.

The “error,” if indeed inadvertent, has been reproduced in mainstream news outlets and state-run media and in government websites such as those of the Philippine Consulates General in San Francisco and New York and the Climate Change Commission. It seems unlikely that Bongbong ordered that his place of birth be changed to that of his paternal grandfather, since such information can be easily verified. However, one wonders if he has not noticed the relocation of his birthplace on his website, which superseded bongbongmarcos.com after he became “PBBM.” The profile is otherwise fairly factual, even stating at least one truth that Bongbong himself does not accept: the fact that he was defeated in the 2016 elections.

“Historic Visit”

There are other lies, also easily verifiable, that Marcos has recently echoed and amplified himself. On September 23, 2023, Marcos was in Iriga City, Camarines Sur to distribute sacks of seized smuggled rice to 4Ps beneficiaries. Both the PCO and the Philippine Information Agency reported on a claim made by Marcos that because of that visit, he is the first president in 55 years to come to the Rinconada (5th) District of Camarines Sur, which is made up of Iriga City and the towns of Baao, Balatan, Bato, Buhi, Bula, and Nabua; purportedly, the district’s last presidential visitor was Marcos’s father, Ferdinand Sr. The alleged source of the claim repeated uncritically by Marcos is Camarines Sur 5th District Representative Migz Villafuerte, who first entered politics in his early 20s in 2013. Both the young Villafuerte and senior citizen Marcos appear to have forgotten about a 2016 visit to Iriga by President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino. That the visit was in line with the campaign of the Roxas-Robredo tandem endorsed by Aquino should be a non-issue, given that Bongbong mentioned that his father’s first visit to Iriga, back in 1965, was also for electoral purposes.

If any and all visits count, Noynoy also went to Iriga in 2012 to visit two wakes—that of then Secretary of Justice Leila de Lima’s father and that of Private First Class Arwin Martirez, who was killed in action in Basilan. If only working visits are counted, President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo went to Iriga on Sept. 4, 2008, as part of a tour of projects being done for Camarines Sur. She attended a briefing on the Bicol River Basin Development Project there. Only President Duterte appears to have never visited the Rinconada district while he was in office, though he did conduct an aerial survey of areas in Camarines Sur hit by Tropical Depression Usman in January 2019, which included Iriga, Nabua, Bula, and Baao. Even that should be sufficient to challenge Marcos’s claim that only presidents named Marcos have visited the district or Iriga in particular (“Marcos lang ang bumibisita sa inyo na pangulo [dahil] malapit kayo sa puso namin”).

“Founding Figure”

Charitably, Marcos’s fib about his “historic visit” was simply an attempt to endear himself to a captive audience. But one questionable claim he recently made may have been designed to suggest that he had political clout independent from being a Marcos or being a close associate of another political juggernaut, the Dutertes. On Aug. 24, 2023, an oathtaking of new members of Marcos’s political party, the Partido Federal ng Pilipinas (PFP), was held in Malacañang Palace. Marcos gave a speech, stating that the party was “Headed of course — who has been helmed really since the beginning of the campaign by Governor Jun Tamayo. But of course the origin of this goes back to my first run as vice president with General Tom Lantion that he – siya ang nauna that proposed this.” Marcos ran for vice president in 2016, while he was a member of the Nacionalista Party.

Based on archived versions of the party’s currently inaccessible website, PFP’s president when Marcos joined the party back in 2021 was indeed South Cotabato governor Reynaldo “Jun” Tamayo Jr. PFP’s first leaders/founders include former Land Bank of the Philippines director Jayvee Hinlo and former Department of Agrarian Reform secretary John Castriciones. Castriciones was also the founder of the Mayor Rodrigo Roa Duterte-National Executive Coordinating Committee (MRRD-NECC). In October 2018, PFP was formally accredited by the Commission on Elections. Bongbong back then was a private citizen, having lost his bid for the vice presidency. Even during the 2019 elections, with a Marcos (Imee) running for a national position, PFP was associated with Duterte, not Bongbong. Marcos’s entry into PFP in October 2021 was not without controversy; Castriciones was among those booted out of the party’s leadership before Marcos became the party’s standard bearer. Also preceding Marcos’s entry into the party was the designation of his legal counsel and later short-lived executive secretary Victor Rodriguez as PFP’s executive vice president; in November 2022, Rodriguez was also kicked out of PFP for “acts inimical to the party” and being an “undesirable civil servant.”

A few months after Marcos won, an article in the Manila Times gave the longer version of the PFP’s (revised) history, as told by Lantion and Atty. George Briones, who were indeed with the party from the beginning. Hinlo and Castriciones are not mentioned by name, nor is Rodriguez given any mention. Lantion describes himself as Bongbong’s security when the latter was studying in La Salle Greenhills, as well as a former close-in security of Ferdinand Sr. Briones called Bongbong a “political genius” responsible “for making the PFP what it is today.” But even this Marcos-focused narrative does not state that they had anything to do with Marcos’s vice presidential campaign, though in another twist (contradicting all previous claims and publicly available documentation), Lantion told the Daily Tribune back in July 2023 that Marcos in fact became a member of PFP on October 5, 2018, the day the party was accredited.

During the Malacañang oathtaking, Marcos also claimed that PFP was the “majority party.” Either Marcos does not understand what a majority party is, or he is overselling the strength of his party, which still seems slow in attracting newcomers, even if PFP’s most prominent members currently include himself and his son, Ilocos Norte First District Representative Sandro Marcos. Sandro, along with a little over a dozen governors and a few presidential appointees, became the newest members of PFP during the August oathtaking. A Manila Bulletin article on the father-son joining correctly states that the “dominant political party in the House” is Lakas-Christian Muslim Democrats (party president: Marcos’s first cousin, Martin Romualdez), but notes that that party is “closely linked” to PFP. Perhaps Bongbong is simply being truthful about the state of party politics in the Philippines.

Youth Act author

There is a grain of truth in another false claim that Marcos recently reiterated: that he is the main author of Republic Act No. 8044, or the Youth in Nation-Building Act. In a recorded message for the commemoration of the establishment of the National Youth Commision, uploaded on August 12, 2023, Marcos said that “in [his] time as congressman,” he authored RA no. 8044, “the law that created [the commission].” He also said that when he was senator, he also authored RA 10742, or the Sangguniang Kabataan (SK) Reform Act of 2015, a slightly less (but still) controversial claim.

Since 2017, after the legislative histories of post-EDSA Revolution laws became accessible online through the House of Representatives’ Legislative Information System or LEGIS, Marcos’s role in the development of the Youth in Nation-Building Act has been fact-checked or contextualized several times. Records clearly show that Marcos was the principal author of one of several bills seeking to create a youth body during the Ninth Congress (1992-1995), and that these bills were substituted by House Bill no. 11614, whose principal author is Jaime C. Lopez of the City of Manila’s second district; Marcos is listed as second co-author, after Zamboanga del Norte’s Artemio Adasa. Lopez was one of the first members of Lakas-NUCD, President Fidel Ramos’s coalition.

LEGIS further shows that Marcos was not the first to file a Youth Commission bill during the Ninth Congress. First was HB no. 15, filed by Lopez in June 1992; second was HB 2872, “An Act Establishing a Permanent and Continuing Youth Leadership Development Institute, and Appropriating Funds Therefor,” filed by Adasa in September 1992; third was Marcos’s HB 4660, filed on November 16, 1992; and fourth was HB 4936, filed on November 23, 1992 by Dante Liban of Quezon City. Even earlier, in February 1988, during the Eighth Congress, Adasa had already filed HB 5400, “An Act Creating the Philippine National Youth Commission, Defining Its Powers, Functions and Responsibilities, and Appropriating Funds Therefor.”

During the consolidated bill’s second reading, it had six sponsors. Ramon Durano III, as chair of the House Committee on Youth and Sports Development, gave his sponsorship speech first; Marcos was fourth in line. Voting unanimously, the bill was approved on third reading by the House on March 21, 1994. The bill was soon transmitted to the Senate. Numerous revisions were made to the Senate counterpart bill, SB 1977.

There is no readily available evidence that Marcos actively participated in the reconciliation of SB 1977 and HB 11614. Reportage of his activities in May-June 1995 suggest that the legislator was mainly preoccupied with protesting his electoral defeat and the ultimately unsuccessful attempts to keep his mother, Imelda Marcos, from occupying the congressional seat that she won. Thereafter, in July 1995, citizen Bongbong also had to deal with his conviction for several tax cases.

Moreover, news articles regarding the Youth Commission bill within the year of its enactment stated that Jaime Lopez was the bill’s principal author, or mentioned Bongbong as being key to the law’s finalization or enactment. Lopez appealed for the Senate to pass the measure, which, again, had been through numerous revisions in the upper chamber.

A Philippines Free Press article, dated July 29, 1995, states that “the [youth] commission’s creation was a hard-won battle” as “youth leaders had vigorously lobbied the 8th and 9th Congresses for its creation.” Indeed, it seems that the only times Bongbong’s role in the creation of the National Youth Commission was highlighted before the RA no. 8044’s enactment were in articles specifically about Bongbong. For instance, an article in the Sept. 18, 1993 issue of the Manila Bulletin, titled “Philippine Youth Commision: Let the Young Voice be Heard,” is accompanied only by four photos of Bongbong, with captions “A body like PYC is urgently needed,” “They oppose it because of who I am,” “I was a rebel teenager too,” and “I want a peaceful life for my son.” The article said that he was “making the rounds of youth groups to collect suggestions, recommendations and needless to say support for the PRC bill,” but there were accusations that he “will just use this as a vehicle for [his] own political ambitions.” Again, Marcos was one of many (and never principal) proponents, authors, and co-sponsors of a youth commission law. Another article, in Asiaweek‘s July 7, 1993 issue, says that his pet bill “is one to create a Philippine Youth Commission,” but that the definition of youth for him were those ages 15-40; the law that was passed limited the youth to those ages 15-30.

In the same article, Bongbong reportedly stated that he obtained the equivalent of a master’s degree in Oxford, but Asiaweek included a parenthetical fact check: “Oxford says he was granted a non-degree Special Diploma in Social Studies in 1978.”

Given that Marcos was far from the first to come up with a law establishing a Philippine Youth Commission, can he at least claim that he was the most influential legislator in the development of the Youth in Nation-Building Act? In his infamous 1995 interview with Kris Aquino (where he says that he turned seven during his birthday in Malacañang; he actually turned eight) despite a portion where they discuss the youth and the congressman giving a closing statement directed to young Filipinos, Marcos never discussed the pending bill. In his 1994 interview with Jun Urbano (as his “Mr. Shooli” character), despite discussing a range of subjects (and lying about his educational attainment), Marcos did not say anything about the creation of a youth commission. His profile in the July 1992-April 1993 issue of Congressional Highlights, which devoted to the first ten months of the Ninth Congress, does not list the Philippine Youth Commission bill as among his priority bills (among those of neophyte representatives, only the profile of Nicetas Panes of Iloilo lists “An Act to Establish the Philippine Commission on Youth Development and for Other Purposes” among his legislative priorities; Panes was listed as a co-author of both Lopez’s HB 15 and Marcos’s HB 4660). In an opinion column in the Manila Standard, dated April 10, 1995, the late Nelson Navarro noted, “Despite the hoopla generated by his 1992 election to his father’s old congress seat, he has not created any waves in legislation or public debate.” Even a long-time ally, Joseph Estrada, found him unremarkable; in September 1994, the Standard quoted the then vice president saying, “I think Bongbong Marcos still needs more experience; I would advise him to seek one more term in Congress” rather than gunning for a Senate seat. Based on some accounts, such as the editorial of the February 6-12 issue of WE Forum, Congressman Marcos was best known for filing a resolution urging President Ramos to allow Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s body to lie in state in Malacañang and to give the long-dead dictator a state funeral; with less than half voting “yea,” the House did not adopt the resolution.

(Dis)information Center

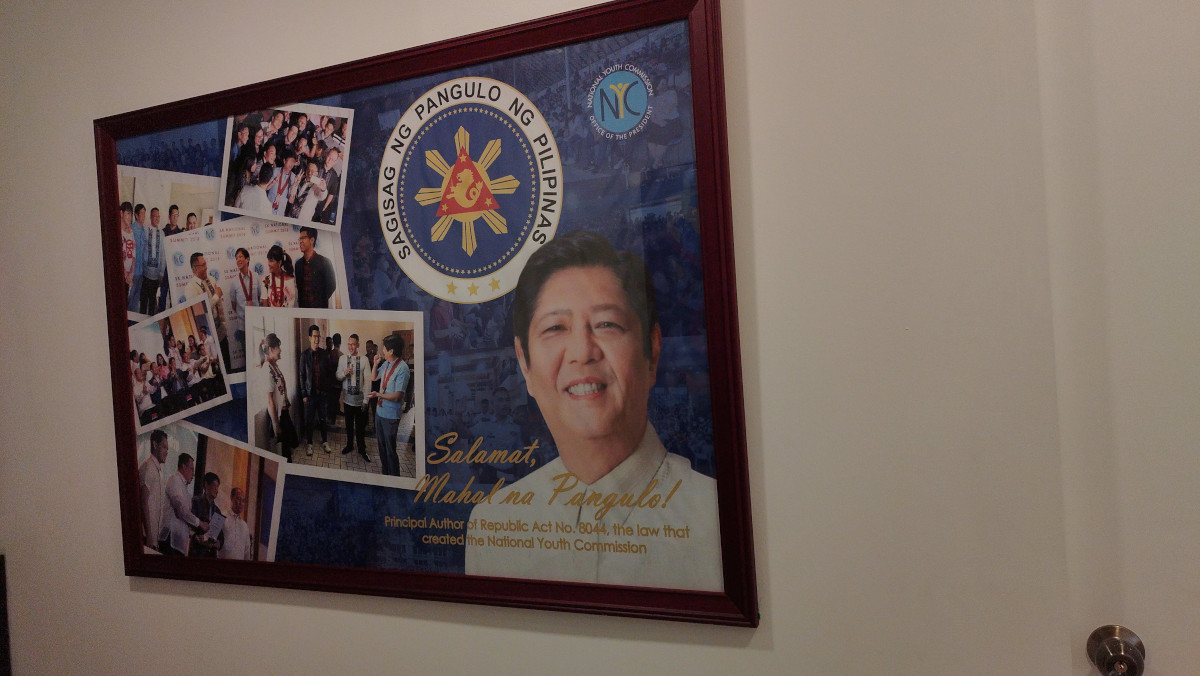

After Bongbong, perhaps the most vocal propagator of the myth that the current president “founded” the National Youth Commission is Ronald Gian Cardema, current chairman of the NYC and leader of the Duterte Youth and the Kabataan for Bongbong Movement. Inside the Bahay Ugnayan, one of the Malacañang Heritage Mansions made accessible to the public in May this year, is a framed photo-collage of pictures showing Cardema with Bongbong (and Imee), emblazoned with the words “Salamat, Mahal na Pangulo! Principal Author of Republic Act No. 8044, the law that created the National Youth Commission.”

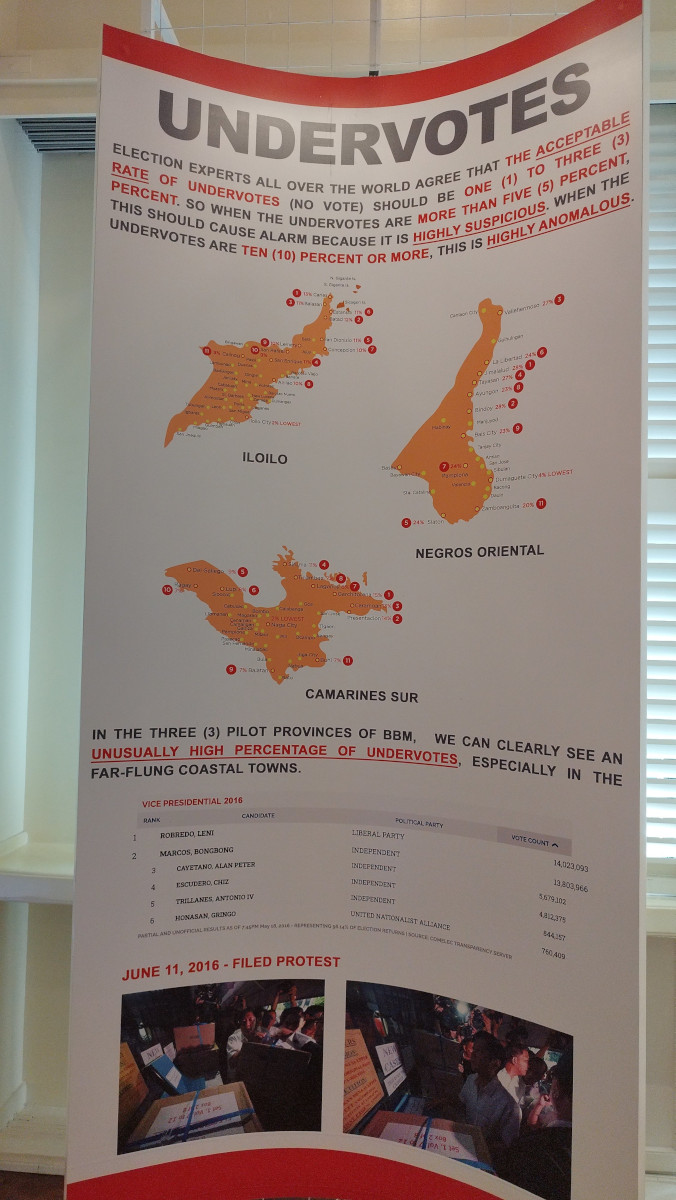

This is one of many lies inside what is essentially a Bongbong Marcos museum administered by an Advisory Board chaired by the president’s Social Secretary, as per Executive Order no. 26, s. 2023. The whole heritage project, which also includes a museum for past Philippine presidents in the Teus Mansion, is attributed to the First lady, Liza Araneta Marcos. Part of Bahay Ugnayan took material from Bongbong’s defunct website (some of which, including school-related records, can still be accessed via Bongbong’s Flickr account). Among these are evidence presented or summaries of claims made by Bongbong to bolster his claim that he was cheated during the 2016 elections, including a crate marked “Iriga City, Cam Sur” and a large poster highlighting undervotes.

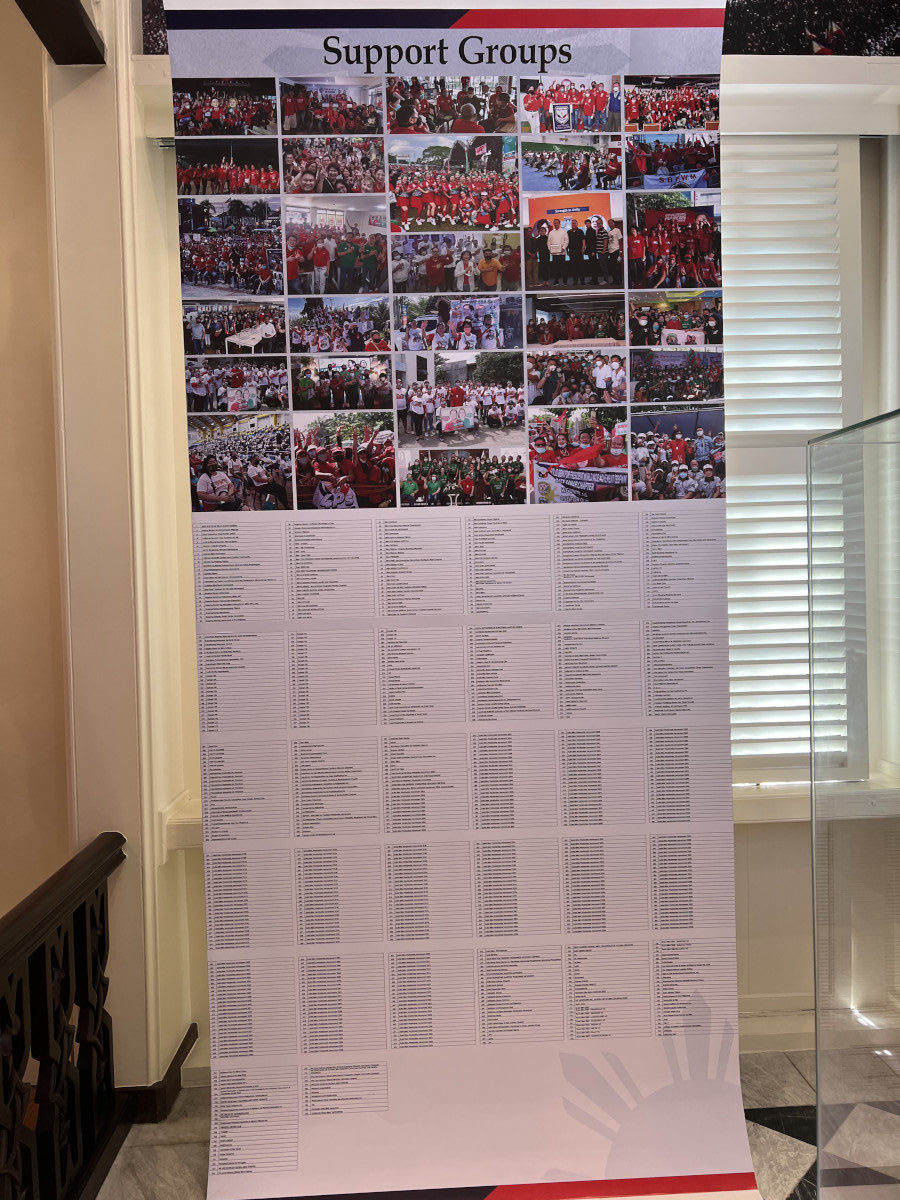

The museum also claims that Marcos graduated from Oxford University, and the reason he discontinued further studies at the Wharton School of Business was his election as vice governor of Ilocos Norte—both proven untrue by documentary evidence (including the Wharton transcript on display at the museum). Besides such tired claims, there is a bit of fudging done by a huge poster titled “Support Groups,” which features photos and a 786-entry list. Entries 365 to 675 are all “Solid BBM Worldwide Movement” followed by a number in sequence from 2022 to 2023; entries 141-203 are all Kasapi followed by a number from 101 to 141. Entries 717-725 all appear to be chapters of TEAM BBM 2022, while 773-779 are all chapters or reiterations of We Love Marcos Global BBM Forever. The last two entries are both Zambales Solid BBM Supporters. Among many similar entries, entry 141, 258, 267, 275, 285, 351, 765, 705, 706, 781 are “Individual,” “Member,” “Motorcycle riders,” “N/A,” “Number 3,” “Selected team leader,” “Student,” “Suffix,” “Vlogger,” and “Womens,” respectively. Marcos’s party, PFP, is simply entry 298 among other “support groups.” After cleaning up the list of bloat, it can be significantly shortened (by more than half), and make one ask exactly who were the “grassroots” supporters of the 2022 Marcos campaign.

All these (among others), Bongbong unleashed within less than a year and a half of his presidency, alongside various other supplementary actions that help give life to the myth of Marcosian greatness—from uploading a copy of the propaganda film that helped elect Ferdinand Sr. in 1965, Iginuhit ng Tadhana, in the Philippine News Agency’s YouTube channel, to removing the anniversary of the People Power Revolution from the official list of 2024 holidays only because Feb. 25, 2024 falls on a Sunday.

Miguel Paolo P. Reyes is a university research associate of the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Reyes, with Joel F. Ariate Jr. and Larah Vinda Del Mundo, are the authors of the book, Marcos Lies. Buy the book here.)