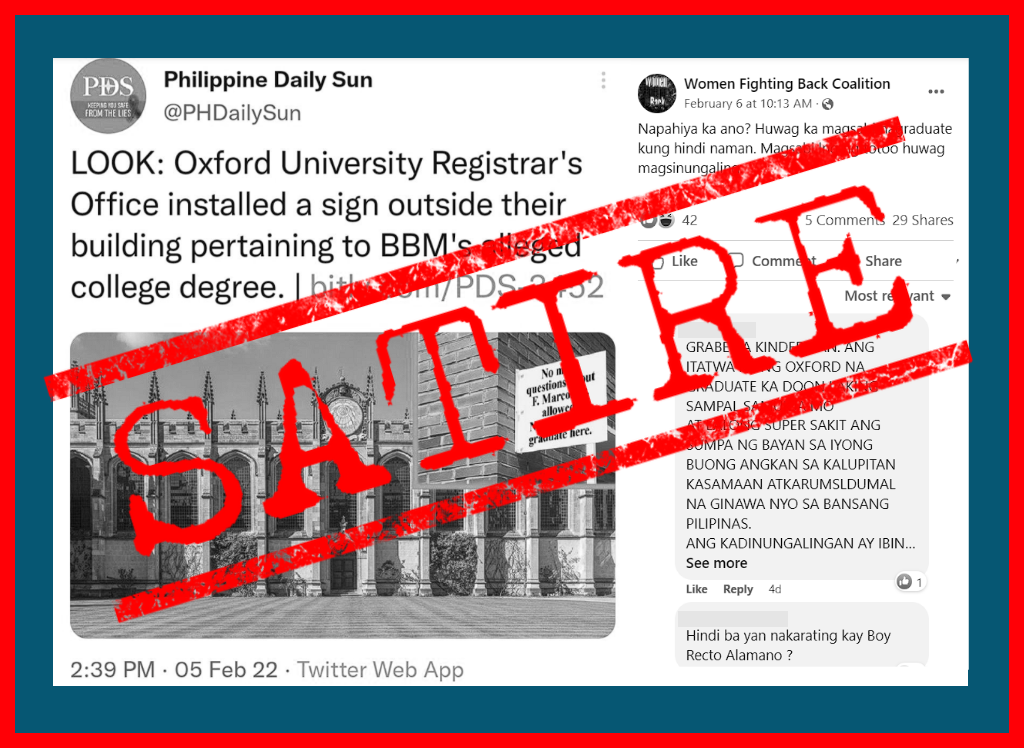

(This two-part article on the ongoing controversy surrounding the educational attainment of Ferdinand “Bongbong” R. Marcos, Jr. is based on pertinent documents and records that shine a light on the facts surrounding the issue. It traces events from 1974 when Bongbong was accepted to Oxford University to 1981 when he dropped out of the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania to become vice governor of Ilocos Norte.)

Speaking at the 25th commencement exercises of the Philippine College of Commerce (now Polytechnic University of the Philippines) on April 1, 1978,the dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos mentioned that his only son and namesake Ferdinand “Bongbong” R. Marcos, Jr. was “still a senior at Oxford.”

“He is graduating this June,” the father said. “He is so busy he could not stay here, he came here and stayed only two days and said: ‘I better go back to Oxford, Father, at ngayon ay naghahanda kami sa final examinations ng June’.”

This was a lie.

The exams that Bongbong was preparing for were not for a college degree in which he had a senior standing. It was for a “Special Diploma in Social Studies.” This, his father knew by late 1976.

President Marcos and his son, Bongbong, share a private moment on the RPS Pangulo. From The Private Face of Ferdinand E. Marcos, produced by the National Media Production Center.

Documents left behind in Malacañang when the Marcos patriarch was toppled and the whole family fled the country in February 1986 tell the story of what Bongbong, who is running for president in the 2022 elections, was able to achieve in his university studies—or what amounted to it—and the Marcoses’ persistent efforts to lie about it.

Bongbong was accepted into Oxford University in October 1975 for a Bachelor of Arts degree in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (PPE), a three-year course. He had passed Oxford and Cambridge’s Schools Examination for summer of 1974 with the following grades in three subjects at advanced level: English literature, C; mathematics, C; physics, C; and the general paper, E. The highest grade in this examination was A.

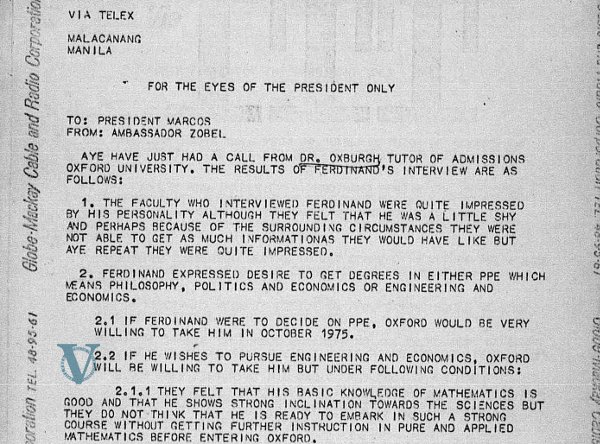

On November 5, 1974, then Philippine Ambassador to the United Kingdom, Jaime Zobel de Ayala, sent a cable to Marcos. He reported that based on his telephone conversation with Dr. Ernest Ronald Oxburgh, Oxford’s tutor of admissions, “the faculty who interviewed Ferdinand were quite impressed by his personality although they felt that he was a little shy.”

During that interview, Ayala wrote that Bongbong “expressed desire to get degrees in either PPE… or engineering and economics,” and that Oxford was ready to accept the young Marcos for a degree in PPE in October 1975, but not in engineering and economics.

“They do not think that he is ready to embark in such a strong course without getting further instruction in pure and applied mathematics before entering Oxford,” the ambassador reported.

Marcos, in a November 25, 1974 letter to Oxburgh, expressed his gratitude to Oxford for accepting Bongbong into its PPE program, calling it the start of a “momentous experience of our young man.”

One year and eight months later, that momentous experience that Marcos had hoped for his son was shattered by Bongbong’s dismal academic performance.

Photo 2 General Certificate Examination 1974-Converted-compressed by VERA Files on Scribd

Photo 3 1974 11 05 Zobel to PFM-converted-compressed by VERA Files on Scribd

Photo 4,1974 11 25 PFM to Oxburgh 1-Converted-compressed by VERA Files on Scribd

In a confidential cable on July 27, 1976, Ambassador Pablo A. Araque, then chargé d’affaires in London, informed Marcos that “Bongbong passed in only one of three subjects he took in the preliminary examination. He passed philosophy but failed in economics and politics.” The diplomat explained that under the Oxford system, “a student who fails whole or part of preliminary examination has opportunity of re-sitting it in September.”

Bongbong had to retake the two exams on September 30, 1976. Tutors were hired to help him prepare.

But Araque continued to be the bearer of bad news. In another confidential cable to Marcos on October 9, 1976, he reported that Dr. John Norman Davidson Kelly, principal of Oxford’s St. Edmund Hall, had informed him that Bongbong “passed in economics but failed in politics. Dr. Kelly expressed deep disappointment at the way things have worked out despite all the efforts and regrets that the firm rule of the college that an undergraduate who fails to clear his preliminary examination at the end of the first year must go out of residence for good now applies.”

Still, the principal threw them a life line.

“Dr. Kelly ended his letter to me quote [‘] if Ferdinand Jr. or you can think of any special circumstances which would warrant the college departing from its normal rule I should be grateful if you would advise me of these as quickly as possible[’] unquote,” Araque noted.

In an October 11, 1976 urgent and confidential cable addressed to Marcos and his wife, Imelda, the embassy official reported on the appeal he and Capt. Artemio Tadiar, Armed Forces attaché to London, made in person to Kelly on behalf of Bongbong, citing the “special mitigating circumstances” that might convince Oxford to relax its rule.

Araque crafted these mitigating circumstances as “(1) Bong’s asthma complicated by flu weeks before his first examination and a similar ailment before the second, exacerbated by the long and exhausting trip back to London from Manila and the abrupt change in temperature [;] and (2) the adverse psychological effects on him after his visit with you (Marcos) to the devastated areas in Mindanao after the earthquake and tidal wave which killed 8000 people and rendered many thousands more homeless.”

Kelly said that he would present the appeal to the 35-member college committee, but cautioned Araque “against over-optimism as favorable decisions in cases similar” to those of Bongbong were ‘very rare’.”

The diplomat told Marcos that according to Kelly, “the rule governing an undergraduate who fails to pass his preliminary examination as a whole after two attempts is not only a college rule but Oxford University rule. In the event that Bong’s case is reconsidered favorably, and Dr. Kelly emphasized that this can only be known after the committee meets, Bong will have to wait until next June [1977] to re-sit his examination in politics. In the meantime, Dr. Kelly is afraid there is nothing for Bong to do in Oxford.”

The committee should have decided the case by the end of October 1976. Whatever the final verdict of the committee, it was clear by then that Bongbong had failed to finish his bachelor’s degree in PPE.

Photo 5 1976 07 27 Araque to PFM 1-Converted-compressed by VERA Files on Scribd

Photo 6 1976 10 09 Araque to PFM (2)-Converted-compressed by VERA Files on Scribd

Photo 7 1976 10 11 Araque to PFM and FL.2-Converted-compressed(1) by VERA Files on Scribd

Photo 8 1978 07 24 Kelly to Tadiar-converted by VERA Files on Scribd

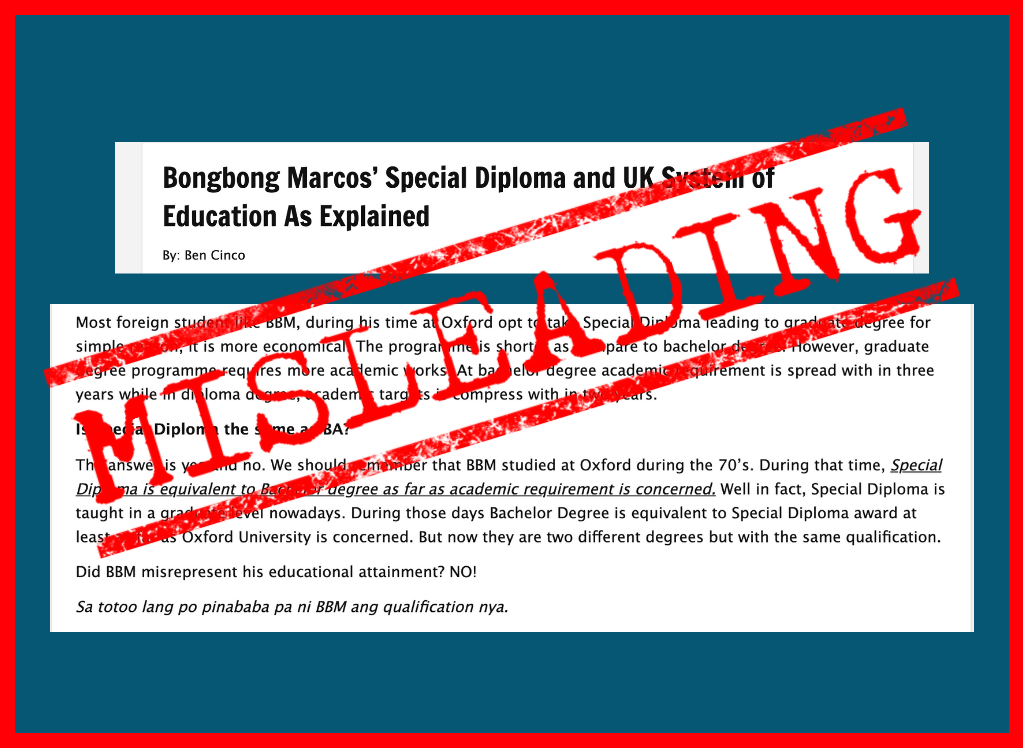

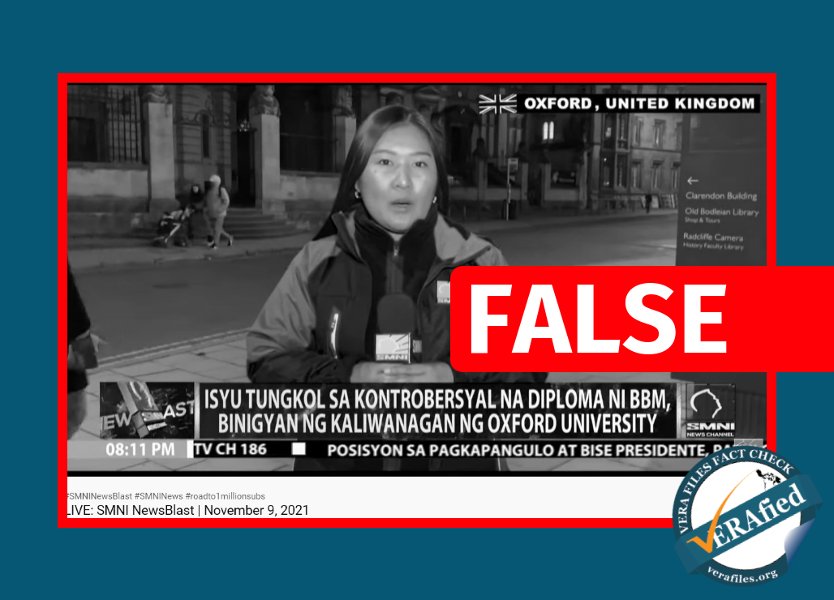

But the young Marcos remained in Oxford until at least July 1978, no longer to pursue a college degree but a special diploma in social studies. Instituted in 1968, this special diploma was “an award to be taken mainly by non-graduates,” according to Norman Chester in Economics, Politics and Social Studies in Oxford, 1900-85,

Under Oxford’s Examination Decrees and Regulations for academic year 1974-75, even non-members of the university “may be admitted as students for the diploma under such conditions as the Board of the Faculty of Social Studies shall prescribe, provided always that, before admission to a course of study approved by the board, candidates, if not members of the University, shall have satisfied the board that they have received a good general education and are well qualified to enter the proposed course of study.” Now discontinued, the special diploma in social studies was one of the qualifications that could be received from Oxford up to the mid-1990s although by then clearly listed under “other qualifications (non-graduate).”

On July 24, 1978, Kelly informed Tadiar of the results of the examinations that Bongbong took for the special diploma. In all five examination papers—one each for political institutions, economic principles, general sociology, economic development, and industrial sociology— Marcos’ son had “obtained a reasonable Class II level.”

“Altogether, his performance in the examination was quite a creditable one, especially having regard to the various distractions to which a young man in his position is inevitably exposed. I think he can go back to his own country with the confidence that, from the academic point of view, his time at Oxford was useful,” Kelly wrote in his letter to Tadiar.

A special diploma, as the Oxford University has made categorically clear recently, “was not a full graduate diploma.” Bongbong has no college degree.

(Joel F. Ariate Jr., Miguel Paolo P. Reyes, and Larah Vinda Del Mundo are researchers at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. This piece is part of their Center’s on-going research program, the Marcos Regime Research.)

(In Part 2 of this article, the authors write about the mystery surrounding the acceptance of Ferdinand “Bongbong’ R. Marcos, Jr. into the prestigious Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania despite his failure to earn an undergraduate degree, his poor performance that led to his eventual withdrawal from the business program – and the lies he and his family told.)