By ELIZABETH LOLARGA

“…Churchill said that dictators ‘are afraid of words and thoughts: words spoken abroad, thoughts stirring at home – all the more powerful because forbidden – terrify them. A little mouse of thought appears in the room, and even the mightiest potentates are thrown into panic.’”—Lara Marlowe, irishtimes.com, June 9, 2012

CALLED “the heroic generation,” these are baby boomers who forsook their parents’ post-war dreams for them to finish a college education, find a stable job and settle down but instead took tremendous risks in defying the state’s force to fight for seemingly abstract rights that today’s youth take for granted, freedom of expression and being able to vote for the President of one’s choice, among others.

With the Filipinos’ much-criticized tendency to suffer from collective amnesia where unpleasant events are concerned, the availability of the collection of essays, Not on Our Watch: Martial Law Really Happened. We Were There, published by the 1969-72 batch of the League of Editors for a Democratic Society-College Editors Guild of the Philippines and edited by Jo-Ann Q. Maglipon, has never been more timely.

The progeny, even the very architects of martial law, are alive, appear to be living it to the hilt, are being hailed for statesmanship and are seriously thinking of a run for the topmost government positions, as though 14 years (1972-86) of dictatorship did not happen.

If the 14 contributors to the book had their way, not on their watch would this happen again.

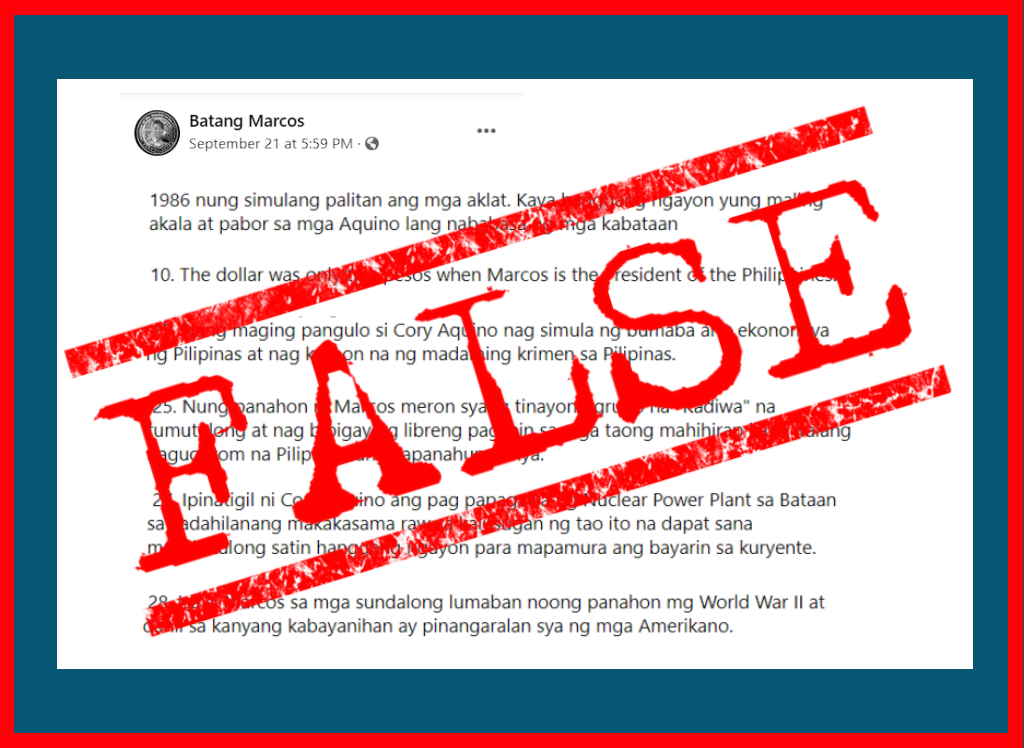

In his introduction, Conrad de Quiros points out how people born in 1986 and after, who’re now in the work force or in middle-level and executive positions have no idea or impression of what one-man rule was like, except for occasional reminiscences from their elders about how cheap rice and gasoline were back then.

He warns that this condition becomes fertile ground for the children and followers of former President Marcos to begin on a campaign of the “Great Forgetting.” The book is part of the “Great Remembering.”

De Quiros writes: “It is not just to be bright enough to become CEO of a big company or succeed abroad, it is to be bright enough to know that you become your best when you serve the people.”

For some who believed in the Maoist line learning from the people, like Jaime FlorCruz, now CNN bureau chief in Beijing, this meant getting stranded in China for decades, experiencing commune life, embarking on a career as a China watcher and turning a “bad thing” (prolonged exile from the Philippines) into a “good thing” (holding one of the most coveted jobs in journalism).

For others like performer Jay Valencia Glorioso, those dangerous times meant being filled with a sense that “I had a lot to do and little time to waste. Activism is always the fuse for change. It is universal. It is an inner call to be a change agent, to act and create events according to our beliefs and desires.”

For Manuel Dayrit, a self-confessed “political innocent” who later rose to be Secretary of Health, the call to rural service was borne out of a realization that the University of the Philippines College of Medicine was graduating doctors who contributed heavily to the brain drain.

He knew the risks of community health service in rural Mindanao but continued despite the murder of classmate Dr. Bobby de la Paz in Samar.

Dayrit writes that those barrio health programs “brought me very close to the rural poor…I came to love the farmers and their families who in their poverty and hardship maintained a quiet and humble dignity.”

Diwa Guinigundo recalls a time when campus newspapers like Philippine Collegian reported more the national situation accurately by exposing human rights abuses than the censored mainstream press.

Vic Manarang and Calixto Chikiamco soberly explain what cronyism was. The control of vital industries like power supply, sugar manufacturing, etc., fell into the hands of Marcos’s friends and relatives. They merely continued the displaced elite’s practice of “rent seeking,” that is, extracting profit from monopolies, licenses and other variations of winning political favors that did not modernize the country’s economy.

The accounts of Sol Juvida and Angie Castillo in colloquial Filipino reflect the anguish of activist mothers who moved from underground house to another either with baby in tow or baby entrusted to relatives or comrades.

Juvida’s struggle parallels her child’s development and growing political awareness. By the time the mosquito press bloomed in the waning Marcos years, her son put up his own makeshift magazine contra the dictatorship to circulate among his classmates.

A glossary of terms concludes this volume that will reveal to new readers martial law’s A to Z from the Agrava Fact-finding Board to what the Young Christian Socialists Movement was all about.