The dictator Ferdinand Marcos was fond of referendums. Mostly sham, of course, his five referendums were an impostor’s way of forging both popularity and legitimacy.

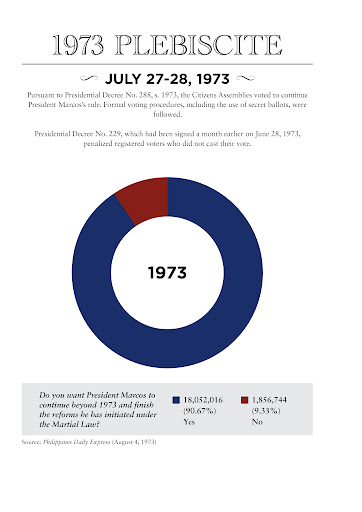

One such referendum was held on July 27 and 28, 1973, asking the people the preposterous question if he “should continue in office beyond 1973 and finish the reforms he has initiated under martial law.” Under the 1935 Constitution, his elective term was to end at the close of 1973. Obviously, he did not wish to relinquish power.

In so-called “citizens assemblies,” the result was 17,653,200 for Yes (90.67%) and only 1,856,744 for No (9.33%). History, the enemy of despots, would later record that many of the 35,000 citizens assemblies never met and voting was by show of hands. There were no ballots. In fact, I am saying this from memory. In 1973, I was 15 years old and in high school.

The dictator would later brag in his diaries: “This is the first time I have won a popular mandate without working for it. No campaigning. No speeches. No expenses. And no headaches.”

Up in the hinterlands of San Francisco, Agusan del Sur, in a barangay called Tagapua, the community of Manobos marched in opposing cadence: they voted No unanimously. What predicated that bravado by a group of indigenous peoples whose story remains in the shadows today?

The Tagapua Manobos tended their farms, raised animals, and did traditional weaving on the sides. Life in that remote barrio was peaceful. It was martial law, and the Philippine Constabulary, the dictator’s dreaded law enforcement agents, would soon appear in Tagapua. They would harass the Manobos and take away their harvests and their animals (carabaos, goats, chicken, swine).

Reaching a point of helplessness, Manobo fury was provoked. And so in the referendum of July 1973, the Tagapua Manobos were assigned one classroom for their citizens assembly. “They all voted NO. 100% NO.” It was their response to the abuse heaped upon them.

But the big No was not to be recorded. A No was embarrassing to the dictator. All the teachers assigned to oversee the voting process were instructed to report 90% Yes and 10% No. The teacher assigned to Tagapua, a Mr. Dollete, did as instructed, recording that the Tagapua Manobo vote was an overwhelming Yes.

That was the match in the powder barrel. In their accumulated anger, they beheaded Mr. Dollete right that instant.

Someone had run to the town to seek the help of the parish priest, a young Dutch Carmelite missionary named Engelbert van Beleteren. The priest then ran to the school supervisor, Porfonio Lapa.

And this is where this story, silenced by the Marcos media for nearly half a century now, is retold by one of its living witnesses, Oscar Labastilla, who lives today. Labastilla was then employed in the Provincial Assessor’s Office. His colleague and roommate was his good friend Baltazar “Baltic” Lapa, the son of the school supervisor.

“Mr. Lapa sought his son Baltic if it was wise to go up to Tagapua to investigate the beheading incident. It was past 5 in the afternoon and we were about to leave the office. Baltic dissuaded his father from going not only because of the situation but because it was getting dark. Mr. Lapa said he was not feeling well but that he had no choice because it was his responsibility. He felt confident because he was accompanied by the Dutch priest, a policeman surnamed Enot, and a teacher.”

“Around midnight we were awakened by policemen. At the town morgue, we saw the corpses of all four who were beheaded. They all took the brunt and the rage of the Manobos for the abuse and atrocities they suffered” from the martial law enforcers.

And then the carnage began.

The Philippine Constabulary stormed Tagapua the next day. “They murdered every man, woman, young or old, wiping out the entire Manobo community numbering 300 in a cinematic massacre spree.”

Labastilla’s daughter Skeeter narrates the bloodbath in her Facebook account, pleading to readers to “please share this story so it will live, until we awaken that violence and oppression is never the answer.” Skeeter led me to her father Oscar, who was 28 years old at the time of the massacre. He is 76 today and lives in retirement in Bohol.

How did the dictatorship manage to hide this story? There was blanket censorship: The dictator expressly prohibited any material critical of the military or law enforcement agencies. All media materials had to be cleared by the Department of Public Information. There was a Committee on Mass Media that was controlled by the military. That was the gist of his Letter of Instruction No. 1 dated September 22, 1972. The masacre was not a news report of “positive national value” as was allowed only by DPI’s Department Order No. 1 dated September 25, 1972. The Tagapua Manobo massacre was destructive of martial law’s image that the dictator had attempted to deodorize at the time.

Ferdinand Marcos was a master of historical revisionism right from the source. Hence, here’s the false news of today propagated by their well-funded troll farms: The victims of martial law were delinquents of society — communists, activists, protesters, criminals, the “pasaway,” the dregs, much like how Rodrigo Duterte justifies his killing spree of mass murder. It is a very convenient canard that appeals to the many who are gullible. The Tagapua Manobos were none of those. They simply voted honestly.

It is humanity that is reduced when the truth is deliberately hidden. That is what the dictatorship did to us, and that is what ails our electoral culture today.Much of the atrocities under the dictatorship continue to fall under impunity. We have to persist taking them out of the shadows of historical revisionism.

What we must do with the Marcoses is continue to hold them accountable, not elect them into office.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.