Experts from the University of the Philippines (UP) Manila and the Australian National University (ANU) reported that different types of media systems in Southeast Asia (SEA) are vulnerable to specific kinds and sources of disinformation.

“The form of media system affects the form of disinformation likely to thrive, including the quality of disinformative content and how it is disseminated,” said UP Manila Department of Social Studies associate professor Jose Mari Lanuza.

ANU Department of Political and Social Change doctoral candidate Cleve Arguelles, Lanuza’s co-researcher, added that “media system features shape the institutional incentives that make some forms of disinformation more likely than others.”

Arguelles and Lanuza’s study was presented in a Dec. 9 forum titled “Where’s the Lie? Research Findings on Disinformation,” organized by The Consortium on Democracy and Disinformation (D&D;), De La Salle University Jesse M. Robredo Institute of Governance and the Asian Center for Journalism of Ateneo de Manila University.

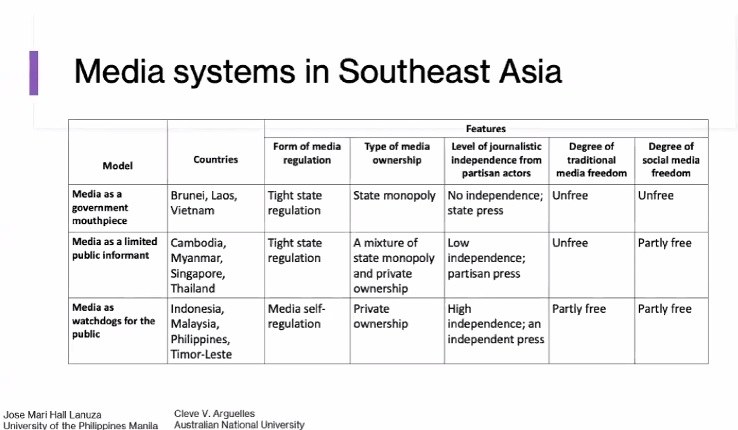

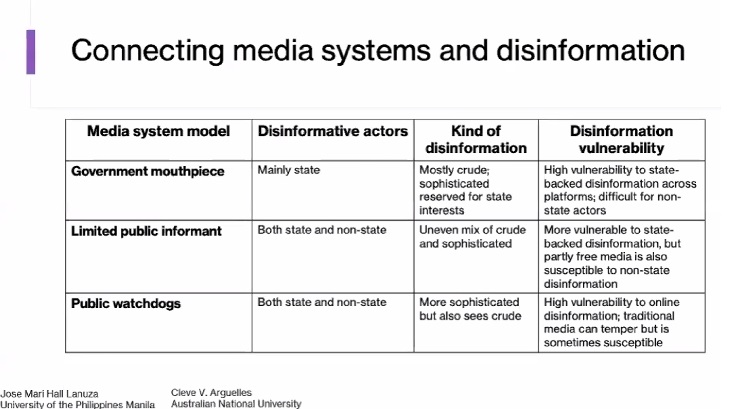

The study classified media systems in SEA as “government mouthpiece,” “limited public informant,” or “public watchdog.” It also determined factors that affected the type of disinformation in each media system.

A table showing the different media systems in Southeast Asia and its features. Screen capture taken during the “Where’s the Lie? Research Findings on Disinformation” held on Dec. 9.

Arguelles said the study defined media systems by asking “who has control of the media and for what purpose its power is used,” determining the type of regulation and journalistic professionalism, and questioning the media’s role as defined by political dynamics in each SEA country.

The Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Timor-Leste have a “public watchdog” media system, where the media has a “significant role in advocating for public interests.” For Lanuza, its free and deregulated press makes it more vulnerable to online disinformation propagated by state and non-state actors.

“The competition for voices and content allow both camps to innovate and pursue new ways to create disinformation, Lanuza explained.

He added that public watchdog media systems are also more vulnerable to sophisticated disinformation, which involves advertising and public relations firms or networked individuals working with either the administration or opposition.

A table showing the disinformation vulnerabilities of different media systems. Screen capture taken during the “Where’s the Lie? Research Findings on Disinformation” held on Dec. 9.

Meanwhile, Arguelles argued that authoritarian countries like Brunei, Laos, and Vietnam have a government mouthpiece media system where “the state exercises total control of the media environment to ensure that the media functions as the throat and tongue of the government.”

Lanuza noted that, in this media system, most disinformation is crudely made by state-sponsored individuals, with complex disinformation reserved for issues of national interest. Citizens outside the government have a hard time spreading disinformation due to the state’s tight media regulation.

Finally, countries like Cambodia, Myanmar, and Singapore have a media system working as a limited public informant where the media regularly serves the need of the public for credible information, but the government often challenges the limits and nature of that role.

This type of media system is more vulnerable to state-backed disinformation because the governments of these countries own most of the media corporations. However, privately owned and partly free media is also susceptible to disinformation from partisan individuals or groups, Lanuza said.

How do the study’s findings help us?

Asked by forum moderator and Philippine Daily Inquirer columnist John Nery on how their findings can be applied to Grade 6 teachers and in promoting media and information literacy (MIL), Arguelles underscored the importance of “raising the alarm on the call of many groups to focus on media literacy as a way to combat disinformation.

“Given limited resources, it burdens the educators to actually combat, teach their students to fight disinformation… We think it tends to forget the systematic level of disinformation vulnerability,” he said.

The ANU doctoral candidate pointed out that MIL is “useful only in high media systems where you can choose which platforms you can go to, which media outfit to consume.”

“In some media systems, there isn’t that kind of option for you. In state-backed media systems, what is the role of a very literate and empowered citizen if wala ka din namang (you also don’t have) choices in the media you would consume?” he asked.

Lanuza admitted that researchers like him find it difficult to propose actual solutions to very specific problems such as disinformation, especially in pointing out who should be at the forefront of combating it.

“Is it really up to us? Should we be choosing our own fate? Or is there a more insidious network that we’re being led to ignore?” he asked.

He urged the audience to “resist having the burden passed to the individual level because there are systematic processes of disinformation at play.”

For Lanuza, the study helps “spotlight these invisible networks, groups of sponsors of inauthentic coordinated behavior.”

“When we shed light on those dark spots, we start the winning fight against disinformation.”