Despite the Marcos administration’s penchant for tucking in various forms of “ayuda” for the poor in the annual budget, the latest Social Weather Stations (SWS) survey showed a significant increase in the number of Filipino families who rated themselves as poor.

In fact, the polling firm noted that the self-rated poverty of 63% in December, up from 59% in September 2024, was the highest in 21 years when it hit 64% in November 2003.

This was also despite indications that “poor families have been lowering their living standards, i.e., belt-tightening,” SWS said.

One thing should be clear to the administration, particularly Congress: more “ayuda” does not make an impact in reducing poverty. They should take a cue from the SWS survey to overhaul their poverty alleviation strategies.

The rising number of Filipino families that consider themselves poor likewise indicates the administration’s dismal failure to control inflation.

The survey, conducted from Dec. 12 to 18, found that the self-rated poverty threshold — meaning, the minimum monthly budget for home expenses needed by self-rated poor families not to consider themselves poor — fell for two quarters last year, from P15,000 in June to P12,000 in September and P10,000 in December.

Simply put, a family needs to spend at least P10,000 a month (down from P15,000 in June and P12,000 in September) to meet the basic food and non-food requirements.

The self-rated poverty threshold was highest in Metro Manila, which rose from P18,000 in September to P20,000 in December. In Balance Luzon, it fell from P15,000 to P10,000, while it remained at P10,000 in the Visayas and Mindanao.

In a press release in October, the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) said the national government’s appropriation for “ayuda,” or cash assistance programs, totaled P318.5 billion for 2024. This was higher than the 2021, 2022 and 2023 allocations, which amounted to P200.9 billion, P276.8 billion and P251.3 billion, respectively. In the 2025 budget, the DBM originally proposed P253.38 billion, but President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. deleted the P50-billion reduction from the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps), which the bicameral conference committee had moved to the unprogrammed appropriations, and set aside P26 billion for the House-initiated Ayuda Para sa Kapos Ang Kita Program (AKAP).

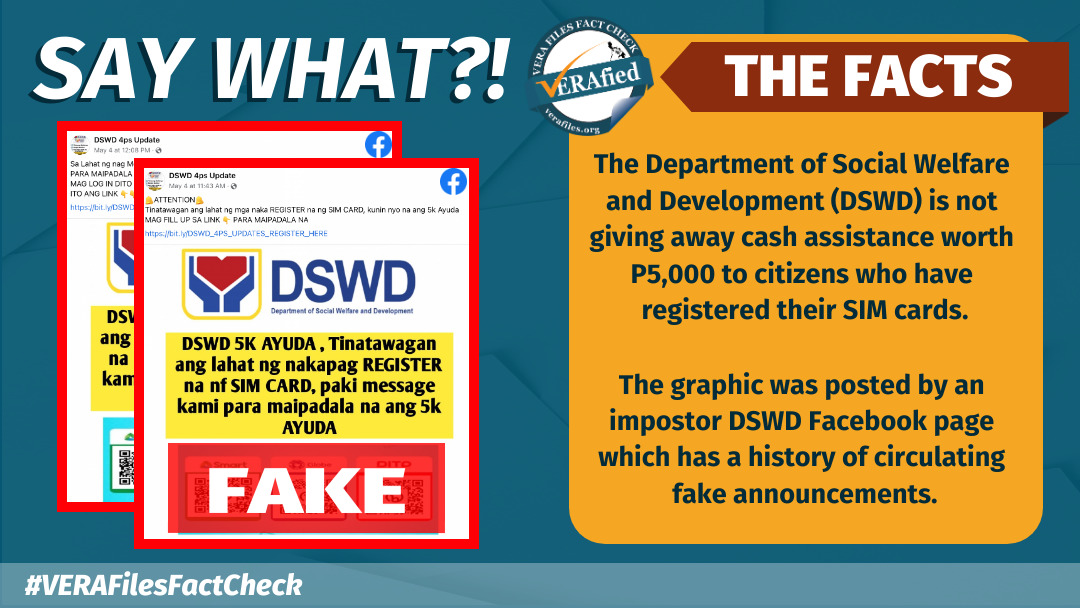

These lump sum appropriations in the annual budget were supposed to serve as the national government’s initiatives against poverty and hunger. These financial assistance programs are being implemented by the Department of Agriculture, including the Rice Farmers Assistance program and Fuel Assistance to Farmers and Fisherfolk; Department of Health’s Cancer Assistance Fund, Medical Assistance to Indigent and Financially-Incapacitated Patients; Department of Labor and Employment’s Tulong Panghanap-buhay sa Ating Disadvantaged Workers Program; and other social protection programs of the Department of Social Welfare and Development, such as AKAP, 4Ps, Protective Services for Individuals and Families in Difficult Circumstances, Social Pension for Indigent Senior Citizens, and granting of additional benefits to Filipino centenarians.

Instead of the intended goal of reducing poverty, these “ayuda” programs seem to institutionalize a culture of mendicancy through a system that promotes patronage politics on all levels, from the barangays all the way to the president.

Every new year, we try to be hopeful for positive developments. But when prices of basic needs and services keep rising despite decreasing and declining quality and quantity, you feel poorer as you lose your purchasing power.

In 2022, the Duterte administration promised that “change is coming,” as it vowed to bring about a “comfortable life for every Filipino family.” After six years, the economy and more Filipino families were worse off.

The Marcos administration claims its goal to eradicate hunger by 2027 and achieve a single-digit poverty incidence by the end of his term in 2028 is on track. Close to its midterm, more Filipino families deem themselves poor. How does it envision dole-outs to improve the lives of the poor?

It’s about time the administration took a serious review of its policies toward the institutionalization of genuine and straightforward programs to uplift the quality of life, not just of the poor, but also of middle-income families, which have long been bearing the brunt of misplaced and mishandled priorities.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.

This column also appeared in The Manila Times.