The key ideologies were Bolivarianismo and Chavismo. The former is named after Simón Bolívar, the 19th century Venezuelan military and political leader who was instrumental in Venezuela’s independence from Spain and who advocated for the unity of Latin American nations.

Chavismo refers to the left-wing populist and authoritarian political ideology based on the programs and governing style associated with Hugo Chávez and his successor, Nicolás Maduro. It combines elements of socialism, nationalism, and Latin American integration, positioning itself against perceived US imperialism and neoliberal economic policies.

Venezuela’s 1999 constitution, approved by a national referendum under Hugo Chávez, adopted the official name of the country as the Republica Bolivariana de Venezuela. As Chávez led an authoritarian government, so did his successor Maduro sustain the Chavismo of his predecessor.

The socialist society it aimed for under a dictatorial government also had elements of cult worship. The secrecy that surrounded Chávez’s whereabouts after he was diagnosed with cancer in June 2011 was standard adoration of a socialist leader – personal vulnerability must be concealed. He “officially died” on March 5, 2013.

In 2015, his former head of security Leamsy Salazar testified that Chávez actually died at 7:32 pm on December 30, 2012. In 2018, Luisa Ortega Díaz, Venezuela’s exiled attorney general, revealed that Diosdado Cabello, president of the National Constituent Assembly (ANC), called her on December 28, 2012, to inform her that Hugo Chávez had died.

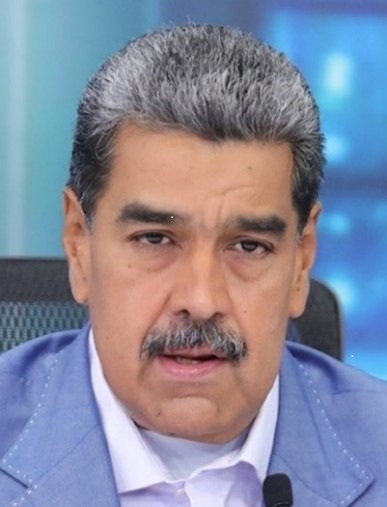

Significant power struggles followed Chávez’s demise, both within the ruling socialist party and with the political opposition. Within the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), the main power struggle was between two factions: Nicolás Maduro, Chávez’s hand-picked successor and vice president who had the backing of the Castro regime in Cuba; and Diosdado Cabello, an influential former military official and president of the National Assembly, who was widely perceived as the favorite of the Venezuelan military.

But Maduro also faced a serious threat to his ambition. He was believed to be a Colombian and not a Venezuelan citizen. In his official biography, Maduro claimed birth in Caracas. The political opposition alleged that Maduro was born in the Colombian border city of Cúcuta and consequently a Colombian citizen. Maduro never produced a birth certificate. His mother, Teresa de Jesus Moros, was recorded in the National Registry of Colombia as having been born in Cúcuta on June 1, 1929.

Under the Venezuelan constitution, that would place Maduro as a Colombian citizen.

What drives strongmen to build dynastic dictatorships? A London School of Economics study maintains that political equilibrium motivates hereditary rule. It “induces better performance from leaders who care that their offspring will follow them in office.”

Perhaps Maduro was rendered insecure by constraints about his citizenship, the specter of political opposition that was supported by Chavismo’s mortal foe the United States, and by his hold on power which could be untenable even within his ruling party. Strongmen operate within a climate of fear and paranoia, even from within their own ranks.

And from 2013 to 2018, Maduro would repeatedly announce one assassination plot after another against him.

The political equilibrium he could see from the socialist political models in his hemisphere were instructive: Nicaragua’s conjugal dictatorship of Daniel Ortega and his vice president wife Rosario Murillo, and Cuba’s Castro brothers who are surrounded in office by family and friends.

Enter his only son from first wife Adriana Guerra, Nicolás Maduro Guerra, known to Venezuelans as Nicolasito. The boy was not schooled in political science nor jurisprudence. His interest was in the arts. Not to worry, his father was the president who could guarantee his political transformation.

In 2014, he was elected delegate to his father’s socialist party. Then his father created a new national office for him, as head of the heavy sounding Special Inspectorate of the Presidency of the Republic. He was 23 years old and had no previous experience in political leadership.

Nicolasito reported that when he travels around the country, he is accompanied by “a large, ‘multidisciplinary’ team of administrators, accountants, journalists, dentists, engineers, and other professionals who share an absolute and unwavering loyalty to Chavista principles.“ He said he then submits his report to his father, the president.

Father also appointed son as Coordinator of the National Film Institute.

Maduro’s other equilibrium ace was his second wife Cilia Flores. She was a deputy in the National Assembly, the equivalent of congress representative in the Philippines. She was political chief of the state socialist party of her husband and a member of the National Constituent Assembly of Venezuela. For all intents and purposes, she was Nicolás Maduro’s Rosario Murillo.

Cilia is no stranger to cronyism. She has been accused of nepotism and of controlling the judiciary.

Equality and justice for all under socialism was not part of the Maduro family’s career goals. Maduro, to be sure, was a scoundrel. It is just a pity that his end came in the hands of another scoundrel. It could have been better under the rule of international law.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.