Images courtesy of the National Museum of the Philippines and Ayala Museum

Every May, the town of Oton, Iloilo celebrates its Katagman Festival where high school students are dressed in colorful costumes, with their eyes and noses covered with gold-colored paper.

Katagman is the pre-hispanic name of San Antonio, Oton where the first gold death mask in the country was excavated by the National Museum in 1973. Located between the Iloilo and Batiano rivers, Katagman was a port settlement and its seaport was one of the most important in the 1300s, as part of the flourishing maritime trade in the region.

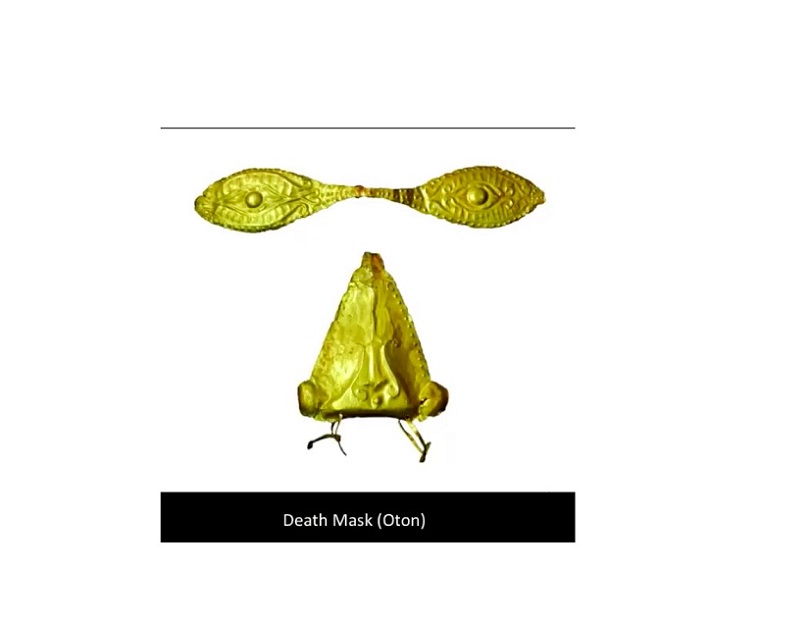

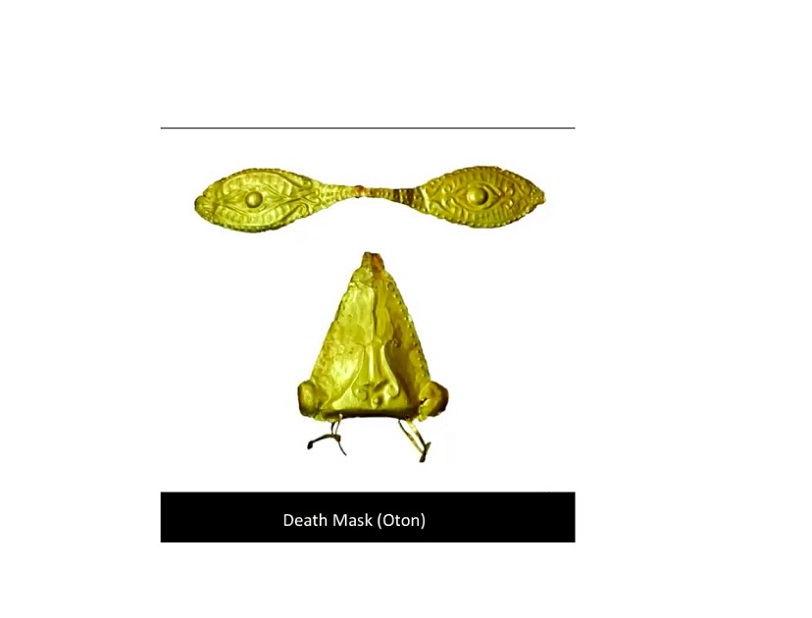

Oton death mask

The death mask in Oton was the first of its kind to be recovered in situ and declared a National Cultural Treasure.

Estimated to be late 14th to early 15th century based on grave goods found nearby, it has two parts: an eye cover, 13.3 cm in length and 2.5 cm in width, and a nose piece, 16.3 cm in length and 5.5 cm in width, and weighs 13.09 g.

Design

Made of thinly beaten gold sheet with hammering and open work, its intricate design is made of swirls and curvilinear motifs as well as “ realistic human features.”

It uses repoussage, the process of hammering thin metal from the reverse side to create a design in low relief, and chasing or embossing in which the metal is hammered from the outside.

Other death masks

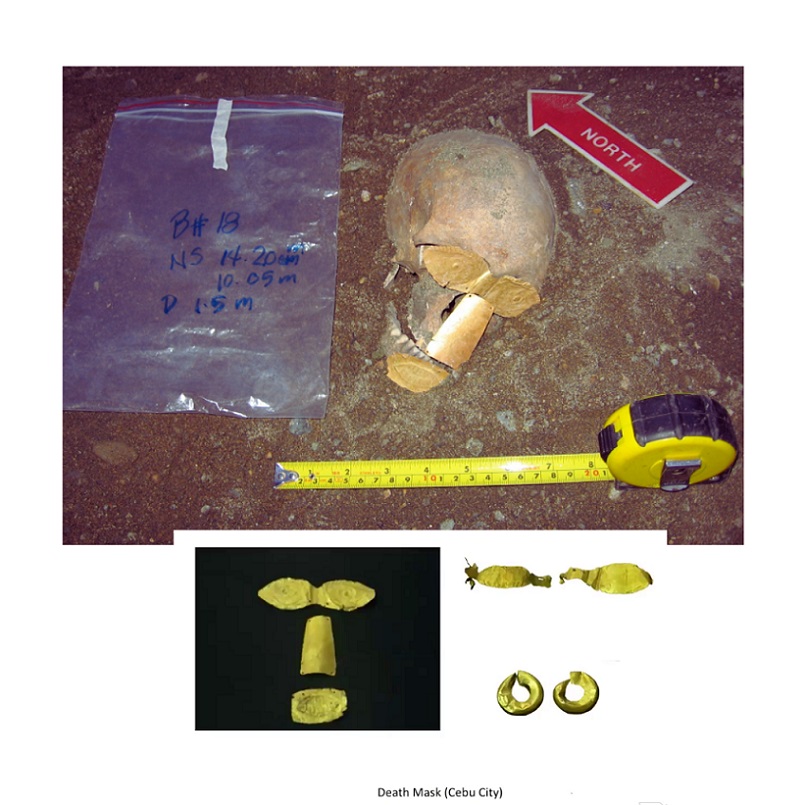

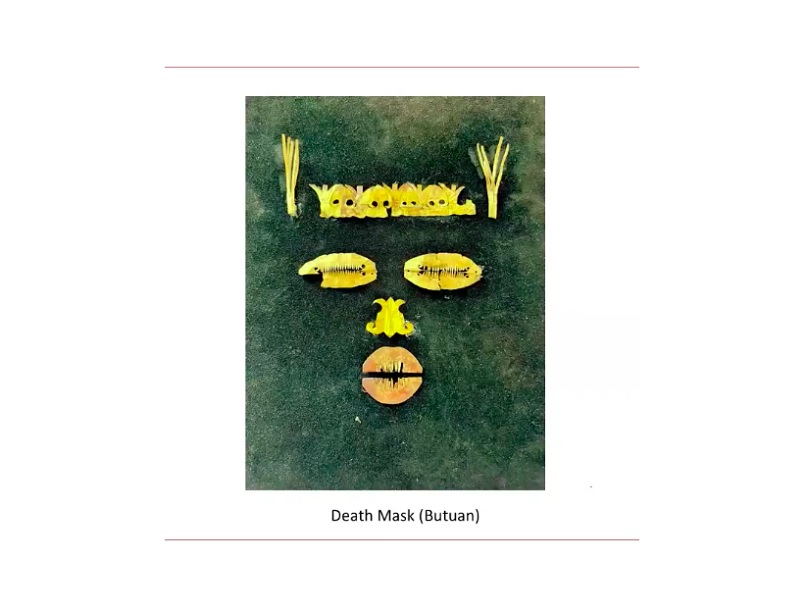

The Oton Death Mask is one among the several gold masks found in precolonial graves and most of ancient gold artefacts found in the country are associated with burial sites. The National Museum has three sets of gold death masks from Oton, Cebu City, and Butuan.

In Cebu City’s La Independencia site, another set of gold mask was discovered in 2007. It is much more simple in design compared with the one in Oton. However, it has three parts: an eye cover, a nose cover, and a mouth cover.

It must be noted that gold orifice covers (for the nose and mouth) are unique to coastal China, Taiwan, and Island Southeast Asia.

Archaeologists say the Cebu gold mask belonged to a person of status, either a chieftain or a head of tribe based on its burial style. The remains were found inside a large ceramic container with the gold mask and a gold dagger.

Ritual and function

Reasons for using gold death masks vary: to prevent evil spirits who are afraid of gold’s brightness from entering the dead body, to guide the newly departed into the ranks of their ancestors; or to protect them from “the profane eyes of the living.”

Gold death masks have been found in other parts of Southeast Asia, such as Indonesia, notably in Bali and Java, in Sarawak, Malaysia and South India. In Makassar, South Sulawesi, gold foil genital and vulva covers have also been found.

Early burial sites

Gold artefacts, mostly ornaments such as rings, chains, pendants, necklaces, and earrings had been recovered in archaeologically excavated burial sites in Central Visayas — Panay, Cebu, Samar, Leyte, Negros and Bohol. Aside from gold, the burial goods usually consisted of ceramics jars, stoneware, and earthenware from Vietnam, Thailand, and China. These burial assemblage also included iron, brass, and copper implements as well as shell ornaments and glass and stone beads, among the most common ornaments found in burial sites.

The afterlife

How did the early Visayans view dying and death? Long before the introduction of Islam and Christianity in the archipelago, the Visayans worshipped nature spirits embodied in celestial bodies and flowing waters, gods of particular localities called diwata, and the spirits of their own ancestors (umalagad). An offering of heirloom wealth or bahandi,in the form of gold and porcelain, in the grave is accompanied by a chant, “May this bahandi accompany our father.” Even in the afterlife, gold seemed to be a marker of wealth and status.

Burying the dead with utmost care is one of the main responsibilities of the living to ensure that the dead is sent satisfied to the next world.

The soul of a Visayan is said to go to a place called sayar where a deity rules. His primary duty is to announce to all the relatives the death of a person, writes the Jesuit priest Ignacio Alcina in his book, La Historia de las Islas y Indios de Visayas (1668). People believed that if they depart rich, they will be well received in the other world.

The historian W. H. Scott described that the Visayans adorned their chiefs and nobles with gold death masks and eye covers. He also noted that the departing dead was delivered to the land of the dead called Saad or Sulad, by boat. On the opposite shore, the soul (kalag) of the dead would be met by his dead relatives, who would only accept him if he was “well ornamented by gold jewelry.”