Manunggul Jar

From the humble clay moulded into earthenware pottery, the clay pot tells the story of our people and our culture long before the existence of written records.

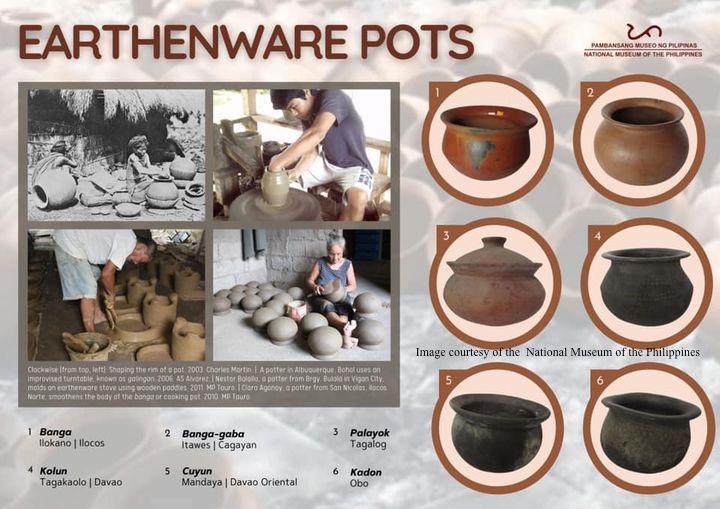

In an online exhibition entitled Palayok: The Ceramic Heritage of the Philippines at the National Museum of the Philippines (http://pamana.ph/ncr/manila/NMA360.html), ceramics tell stories of daily life, celebrations, and trade with other island nations.

Ceramic artifacts are the most common type of cultural material found in archaeological sites around the world. In the Philippines, ceramics (whole vessels or its broken fragments) provide evidence of our prehistoric past such as “population movements, maritime interactions, social identities, ritual practices, and spirituality.”

The exhibit presents the rich ceramic tradition of the Philippines and how it has shaped our culture. It displays several outstanding types and forms of earthenware pottery, found in archaeological sites from Sabtang, Batanes to Maitum, Mindanao that demonstrate the extraordinary craftsmanship of past pottery-producing communities.

Variety of design and form

Prehistory

The arrival of maritime communities 4,200 years ago is mainly associated with the appearance of pottery in the Philippine archipelago. These communities also brought in stone and shell artifacts as well as boat-building and rice agriculture, marking the country’s Neolithic period.

Early pottery evidence has been found in Northern Luzon, the Batanes Islands, Palawan, Masbate, Negros, and Tawi-Tawi. Baked clay spindle whorls (for weaving) and ornaments have also been found in Batanes and Cagayan Valley. Its presence indicates the introduction of textile technologies.

The growth of maritime communities led to more contacts with neighboring Southeast Asia and Taiwan as well as the introduction of new ideas and technology. New designs in earthenware vessels such as the shallow angular bowl with geometric decorations have been found in the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, suggesting exchanges of ideas across the seas.

Prehistoric pottery design includes incisions, impressions, cord marking, and hand painting clay paste while it is still soft or leathery.

Shapes are formed by hand moulding, coiling, or the paddle-and-anvil method and polished with round smooth stones. After shaping into vessels, they are dried under the sun. Firing usually takes place in an open fire using cogon, coconut husks, and wood as fuel. In prehistoric Philippines, no kiln has been found.

Together with pottery vessels, clay ornaments known as lingling-o and pendants as well as clay figurines reveal the primal beginnings of artistic expression in the archipelago, and the making of social identity.

Form and function

Moulding clay and mud, our ancestors produced valuable objects that helped them in their survival against natural elements. Through earthenware vessels, new ways of storage (water, rice, salt, vinegar, or wine) and cooking (rice, meats and vegetables) came about. They are also used for the fermentation of alcoholic drinks, vinegar, and fish sauce. The term tapayan originally refers to a large earthen jars used to ferment rice (tapai).

Burial jars

Rituals and burials

Burying the dead in jars was a widespread practice across the world that includes Sri Lanka, Laos, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Japan from 3,000 to 1,000 years ago.

In the Philippines, burial jars have been recovered from northern Luzon, Marinduque, Masbate, Saranggani, Mindanao, Sorsogon, and Palawan. Made of clay or carved stones, burial jars are usually placed in caves, facing the sea. In the National Museum collection, burial jars come in various shapes: round, rectangular, and quadrangular

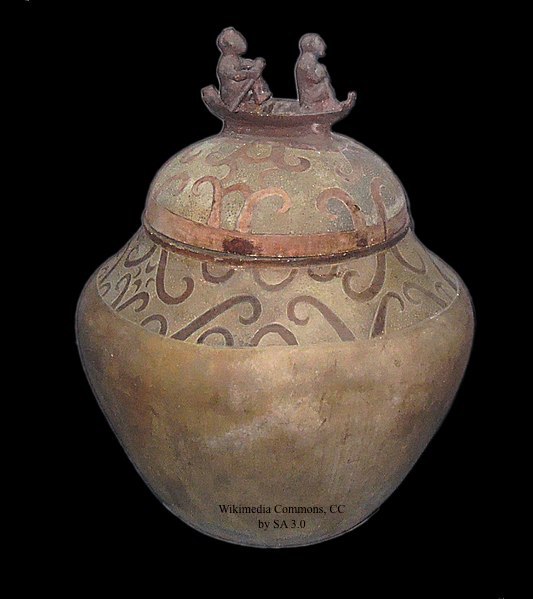

The Manunggul Jar, (890-710 B.C.), found in the early 1960s in Palawan, exemplifies this funerary practice. A secondary burial jar, its upper portion and its cover or lid are incised with curvilinear scroll designs and painted with natural red clay or hematite. On top of its lid is a boat with two human figures. Representing a journey to the afterlife, the figure in front has both hands crossed over the chest, a traditional Filipino practice of arranging the corpse. The boatman, with a paddle, sits behind.

Robert B. Fox (1918-1985), the former chief anthropologist of the National Museum, described it as “perhaps unrivalled in Southeast Asia, the work of an artist and a master potter.”

Earthenware pottery in various shapes and colors has been used as part of elaborate funerary and ritual practices, reflecting the early Filipinos’ complex beliefs in death and the life after.

An enduring tradition

Today, women in rural communities continue to make earthenware pottery as a source of income, aside from farming and fishery. As in the past, clay is collected from nearby sources.It is cleaned of stones and other debris and pounded or kneaded by foot.

Traditional cooking pots, jar, and stoves are made as well as new ones such as vases, planters, wall décor, toys, and bricks. Earthenware pots (palayok inTagalog, kolun in Bisaya, banga/tayab in Ilokano) are used in cooking rice, sinaing na tulingan, pinakbet, and more. It is believed that earthenware cooking makes the food more flavorful. Rice cakes such as the ubiquitous bibingka in town plazas are also cooked in earthenware stoves.