By JINKY CABILDO and MATTHEW REYSIO-CRUZ

(First of two parts)

FIVE grams of “shabu” in his hands and nowhere to run.

It was 17-year-old Daniel’s second brush with the law when two police officers and three city watchmen arrested him in Taguig City one early morning in October last year. (The names of the children have been changed to protect their identity.—Ed.)

Under the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act, children in conflict with the law (CICL) like Daniel should be brought to a temporary shelter for processing within eight hours of their apprehension.

Instead, police kept him at the station. Up five against one, they beat him until his body was swollen. Afterwards, police detained him in a cell with 70 adult prisoners. Desperate to survive, Daniel joined the prison gang “Sputnik,” so he would receive money for medical supplies from members who’d visit the jail.

A month later, Daniel was transferred to the Taguig City Jail where he stayed two more months. One wrong move and the inmates would be beaten by the police. But the senior inmates were also to be feared: When Daniel answered back at one of them, they hit his thighs seven times with a three-inch-thick wooden paddle, which they hide in the water drum inside their cell.

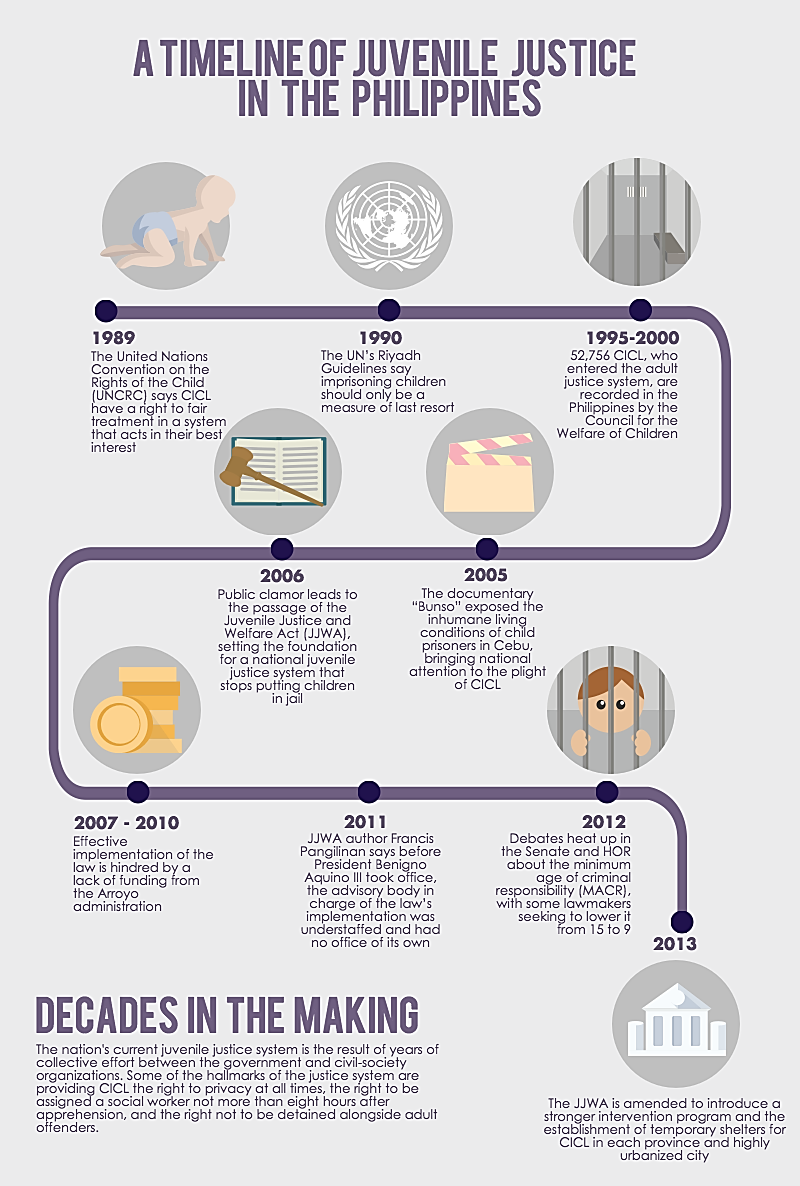

Nightmares like this are exactly what lawmakers sought to prevent when they passed Republic Act 9344 or the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act (JJWA) in 2006 and amended it with RA 10630 in 2013. It created a justice system where children below 18 could no longer be jailed with criminals. Alternative programs awaited them instead in their community or at a Bahay Pag-Asa, their city’s designated government-run shelter. Or so it should be.

Ten years since the passage of the JJWA, children in conflict with the law like Daniel continue to be tortured and detained with adults before they reach a rehabilitation center. At the very first step of the justice system they are put at the mercy of the police, who often lack training and harbor differing interpretations of the law. This happens despite the law’s revised Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR) that call for respect and humane treatment of CICL upon apprehension.

The Ateneo Human Rights Center (AHRC), Humanitarian and Legal Assistance Foundation (HLAF) and Children’s Legal Rights and Development Center (CLRDC) confirmed this is a step in the justice system that continues to be riddled by various instances of neglect and abuse.

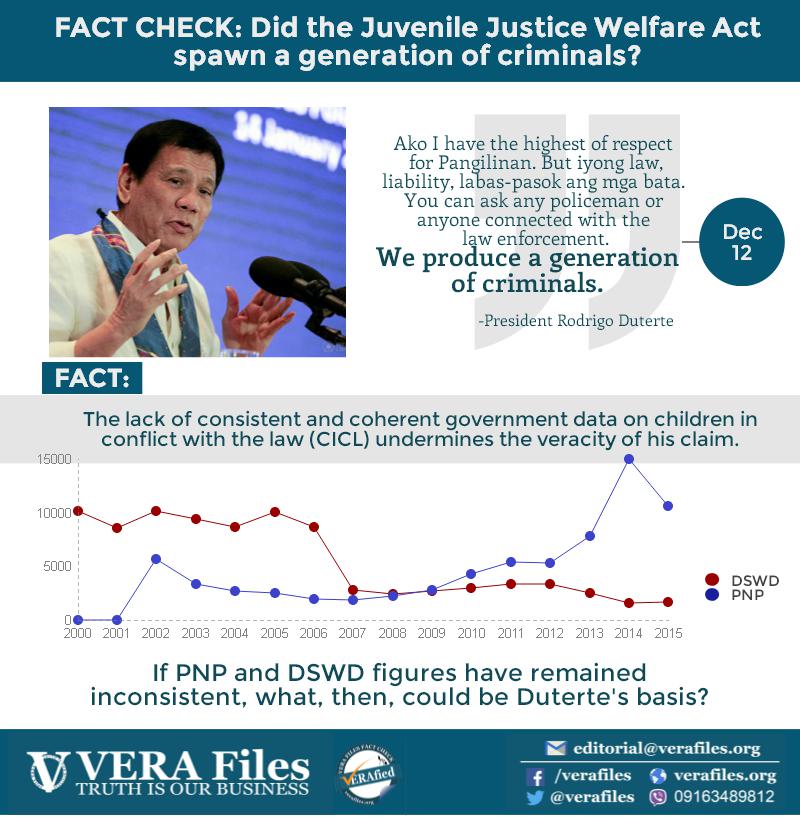

Between 2012 and 2015, the Philippine National Police (PNP) recorded at least 38,682 cases of CICL in the country. About one out of five cases, which may involve multiple children, is from Metro Manila. During the same period, less than 2 percent of CICL in Metro Manila committed heinous crimes such as murder and homicide. Petty crimes were the most common, with theft making up nearly one-third of the cases recorded in those four years.

“(They’re) stealing because they’re hungry, robbing because they need money to help their family,” said Klarise Estorninos, head of the Child’s Rights Desk at AHRC. “We should be protecting our children because they are victims.”

Grave misunderstanding of law costs CICL their rights

The cardinal rule in protecting young offenders is ensuring they are never detained with adults, even as a last resort. But because police struggle to understand the law’s purpose, the rule appears more a suggestion, with grim experiences of detention for CICL still occurring.

Many officers who don’t understand how the juvenile justice system works fake the age of CICL so they enter the adult system instead, said Kim Claudio, program officer at HLAF.

“They really believe that the law removes accountability from children. They say it’s a system that breeds criminals,” said Claudio.

Melanie Ramos-Llana, president of the Philippine Action for Youth Offenders (PAYO), echoed Claudio’s sentiments. “Ten years (since the law was implemented) yet we’re still stuck trying to understand it… Maybe people are just too set in their ways that they cannot think out of the box,” she said.

Police barged into the home of Marcus, 20, to arrest his two in-laws, who carried shabu and drugs paraphernalia. Because he was also there, police apprehended him for robbery and possession of drugs.

Although Marcus showed them his birth certificate to prove he was only 17 at the time, police opposed his claims. They put him in the Pasig City Jail for two months where he was thrust into a world of hardened criminals. It was only after his sister brought his birth certificate to court that a judge ordered his transfer to Bahay Aruga, Pasig City’s Bahay Pag-Asa, which itself took a month to complete.

Archie Salmo, Bahay Aruga’s lone social worker for CICL, said police often refuse to honor birth certificates children present during arrest. She has handled five cases thus far in Bahay Aruga of children under 18 who were sent to adult jails even after the law was amended.

Jill Regalado, a lawyer at the Commission on Human Rights Child Rights Center (CHR-CRC), said the burden of proof should always lie on the police. If CICL claim to be underage, police must believe this unless proven otherwise, she added.

CLRDC’s Executive Director Rowena Legaspi said in Filipino, “They have this culture of impunity because they have the power and authority. They think they can do whatever they want to do, especially with the kids.”

Minors share harrowing tales of police torture

This is the same culture that forced Daniel into joining a gang. He swore after his release from Makati Youth Home, his first order of business will be to find a way to remove the three tattoos he got inside the cell, declaring him a gang member for life, on his knee, upper thigh and at the base of his thumb.

Beyond any physical marking is the unmistakable psychological damage caused by his ordeal with the police. Unfortunately, his case is not an isolated one.

Jansen, 15, once found a home with a drug syndicate operating in the dark alleys of Potrero, Malabon. When his father left for Pangasinan, Jansen turned to shabu and sold drugs to survive. His remarried mother, now in Samar, offered no comfort either, while his stepfather beat him bloody.

“When they fight, he takes out his anger on me,” Jansen, who showed a bruise on his arm that still remained after months, said in Filipino.

But his most severe beating was at the hands of the local police.

While detained at a police station in Malabon last year, authorities tied his hands to a bar overhead, leaving him hanging. They beat his head repeatedly with a plastic water bottle and placed ice on his genitals. Eventually overcome with fatigue, Jansen could not stop his feet from dropping into the tub of water below, where an electric shock coursed through his body.

Jun, also from Bahay Sandigan in Malabon, said a policeman hit the back of his head with a gun when he was apprehended for snatching, leaving a large, still-visible lump at the base of his skull. Jun’s mother swallowed her indignation because police threatened her, saying they would kill Jun if she filed a case against them.

Alex, 16, experienced a similar kind of torture at the hands of Makati police last year when he and his friend were arrested after a botched hold-up. The mastermind of the crime managed to escape, but not before leaving his gun with Alex.

Police confiscated the gun and taunted Alex with it, threatening to shoot. They stole his necklace, iPhone 5S, watch, cap and slippers before taking him to the police station. At 8 a.m. inside the station’s kitchen, Alex and his companion were forced to hold onto a metal bar above them. When they could no longer sustain the position and their feet hit the ground, the police began beating them.

“When they (CICL) encounter the police, there’s a chance they’ll experience abuse. As the child enters the criminal justice system, even if it’s the juvenile justice system, their chances of diversion get slimmer and slimmer,” said Ramos-Llana. The diversion she is referring to are the programs aimed at diverting children away from the formal justice system and entering them into community-based programs instead.

Legaspi said CLRDC’s social workers documented cases in which the CICL were barely recognizable because of their bruises when police brought them to a shelter.

Kim, from New Bilibid Prison’s juvenile division, was arrested by Manila policemen for stealing a necklace worth P300. The officers, intoxicated, took him outside the station and beat him both nights he was there, demanding to know if he had accomplices.

The police, who are required to administer a medical exam to CICL, purposely gave Kim his exam before the beatings, to ensure there’d be no record of the injuries Kim sustained afterward.

Philipp, from Bahay Aruga in Pasig, also reported extortion and intimidation when he and a friend were arrested in 2012. Police entered his friend’s house and failed to find the suspect they came for, bringing them to the station instead, where Philipp said evidence against them for drug possession was planted. Authorities collected Philipp’s Samsung Galaxy phone, a necklace, a ring and his hard-earned money from babysitting, an amount close to P3,000.

In exchange for their release, police demanded P500 million each from Philipp and his friend by noon the next day. Both their families failed to raise the amount. Four days later, Philipp, 17 at the time, was transferred to Bahay Aruga.

As a result of the abuse CICL experience at the hands of police, it is possible they would develop psychiatric conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder or anxiety disorder, said Dr. Violeta Bautista, director of the University of the Philippines Office for Counseling and Guidance.

Bautista added that torture can also lead to the child’s loss of trust in the government.

“The police are supposed to protect you, and it really says a lot to kids when those who are supposed to protect you are the ones who abuse you. So what happens? The child loses faith in the system, the structure and the authorities,” she added.

Power-tripping prevents justice for juveniles

Common to all the CICL who experienced abuse at the hands of police is they did not file a formal complaint about what happened.

“It’s only going to hurt me in the end,” said Kim in Filipino.

Jansen didn’t tell his social worker at Bahay Sandigan in Malabon about the police abuse either. “They won’t help me even if I tell them,” he said in Filipino.

Rowelyn Acdog, a social worker in Yakap-Bata Holding Center in Caloocan, said parents who file cases against the police for hurting their children rarely receive justice. Instead, they find themselves threatened by authorities.

If this does not work, Acdog added police just talk to the CICL’s parents and pay them a hefty amount to settle the case.

Police Chief Supt. Rosauro Acio, head of the Women and Children’s Protection Center (WCPC), said the CICL’s accounts of police brutality may refer to the “reasonable force” cops must use to contain especially aggressive CICL during apprehension. He denied receiving complaints or hearing any news regarding police torture of CICL.

Chief Supt. Eder Collantes, the statistician in charge of CICL data, added that such grievances against the police may be formally addressed to various offices within the PNP, including the People’s Law Enforcement Board.

If an administrative case is filed, Acio said it would be given proper attention.

Social welfare office, police ill-equipped to handle CICL

After arrest, police must bring the child to the appropriate agency, be it the Local Social Welfare and Development Office (LSWDO) or the Bahay Pag-Asa, within eight hours.

However, the LSWDO lacks the facilities to cater to large numbers of CICL, the PNP said. Because of this, they sometimes request police officers to keep the children detained at the station, further increasing their vulnerability to abuse.

Nancy Agaid, a social worker with Stairway Foundation, said police told her of social workers who tell them “Pakawalan niyo na (Let them go)” if police apprehend children under 15, rather than taking them to the DSWD or LSWDO, which lacks the space and the staff to accommodate them.

Harry, 16, spent three days in a Cainta jail because the local DSWD office was closed when authorities apprehended him for robbery. Police detained Harry in a cell with 80 adult prisoners because they said he might escape.

Social workers have a lot more authority than people realize. Peter, 13 at the time, was admitted into Molave Youth Home after being apprehended for theft. “I was very hardheaded at that time,” Peter said in Filipino.

He had barely been in the shelter for a week when personnel from the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology arrived to escort him to the Quezon City Jail as punishment for his hardheadedness. He spent three days there with adult prisoners, most of whom were charged with carnapping or murder. The transfer was endorsed by Molave Youth Home’s social worker.

Peter added that they sent him there hoping his exposure to the difficulties of prison life would change his ways. But this deliberate detention clearly goes against the restorative justice principle the law promotes.

Acio hopes the manual for police regarding the protocol for handling CICL, to be released this year, will shed light on what the police should do if such scenarios arise.

As of January 2016, a total of 249 personnel in Metro Manila who have undergone a specialized 12-week course on handling women and children, according to PNP statistics. Of these, 243 are women. There are 44 established women and children’s desks established in the region.

Although these figures indicate progress in understanding the law and proper management of CICL, Normina Mojica, the juvenile justice focal person for the Council for the Welfare of Children (CWC), said some police personnel use the course to primarily attain the credentials necessary to secure a promotion.

“The problem with the PNP is that they use the training as a stepping stone to get ahead. To be promoted. So usually, those you train would only be there for a certain period and then leave,” she added.

Much of this training is just for show, confirmed Jarrett Davis, a research affiliate at Love 146, an international human rights organization that works with child victims of abuse.

“People celebrate too quickly when laws are passed. But until stuff really develops on the ground, it’s meaningless,” he said. “There’s a lot of smoke and mirrors in the legal system.”

Daniel’s experience is a case in point. Earlier this year, Taguig City received the “child-friendly local governance seal” from CWC, proclaiming it the most child-sensitive city in Metro Manila for 2015. This was the second year in a row it won the distinction.

Its programs for CICL were singled out in the awarding. A newspaper account last February said, “The Women and Children’s Desk of the Taguig City Police Station actively protects the rights of the CICL.”

Police in Taguig City marked Daniel’s age as 19 on their record, effectively sending him to a prison for adults. He informed them he was only 17.

But to this, the police simply said, “Kahit 15 years old ka, wala kaming pake (Even if you were only 15, we still don’t care).”

(This report is culled from the undergraduate thesis, “Stolen Second Chances: An Investigative Study on the Conditions Faced by Children in Conflict with the Law in Metro Manila,” done for the authors’ journalism degree at the University of the Philippines-Diliman. The thesis was a finalist in the 2016 Philippine Journalism Research Conference. VERA Files trustee Yvonne Chua was their thesis adviser. The authors now work for the Philippine Daily Inquirer.)