All images courtesy of H.Xhauflair and the National Museum of the Philippines

A groundbreaking discovery of the earliest evidence of plant technology use in stone tools in Southeast Asia reveals the amazing ingenuity and resourcefulness of prehistoric peoples.

The research study titled The Invisible Plant Technology of Prehistoric Southeast Asia: Indirect Evidence for Basket and Rope Making at Tabon Cave, Philippines, 39-33,000 Years Ago (June 2023) has been published by Plos One, a peer-reviewed open access journal by the Public Library of Science.

The authors are Hermine Xhauflair, Sheldon Jago-on, Timothy James Vitales, Dante Manipon, Noel Amano, John Rey Callado, Danilo Tandang, Céline Kerfant, Omar Choa, and Alfred Pawlik.

Archaeological sites in the country have revealed how our ancestors live, work, and play through material remains such as stone tools, fossils, bones, shells, pottery and ceramics, and precious metals and stones.

Among prehistoric peoples. their material culture (just like ours today) consisted of organic materials, mostly from plants such as textiles and tying materials. Organic materials do not preserve well, especially in hot and humid tropical countries.

For the first time, the study reveals the existence of perishable plant-based technology in prehistoric Palawan.

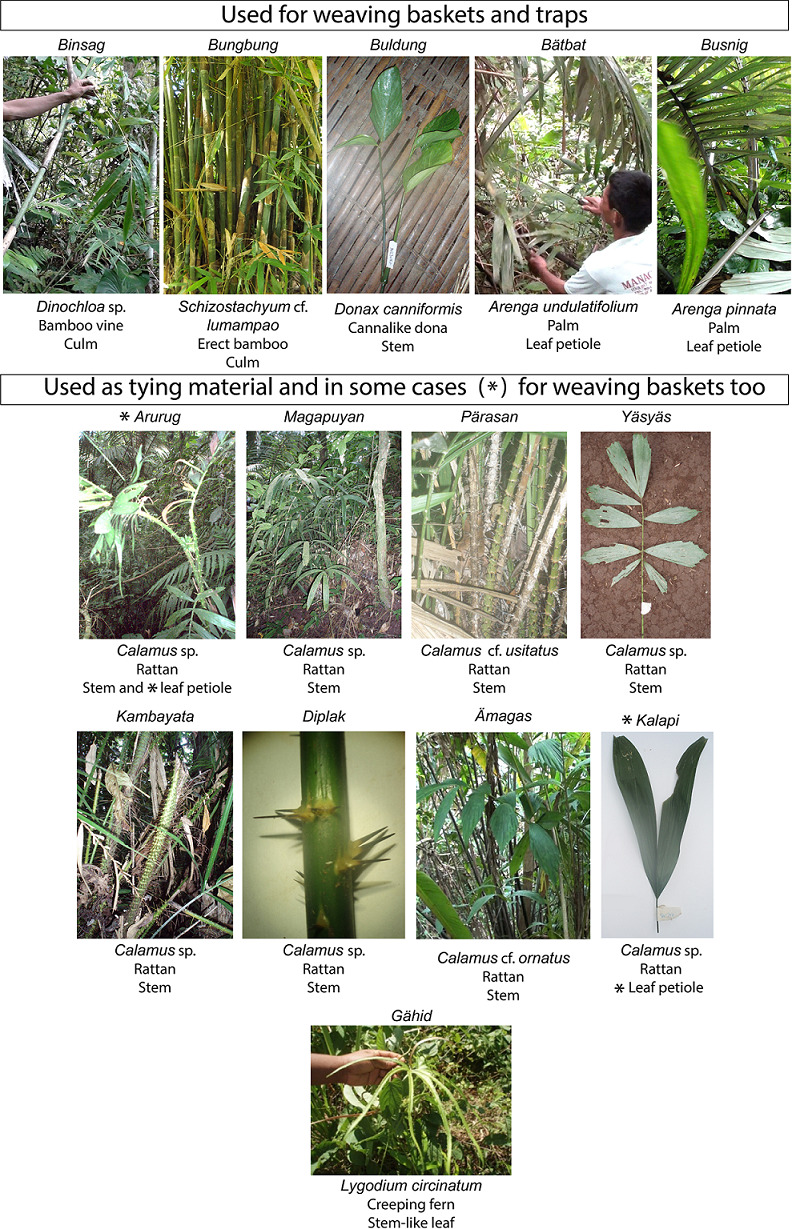

Plants for Basketry and Tying Materials H. Xhauflair 2023 paper

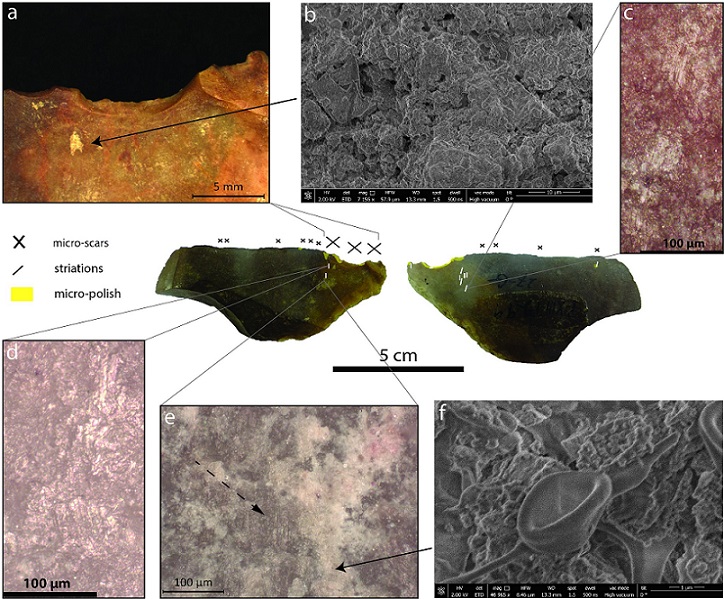

Use-wear and residue analysis

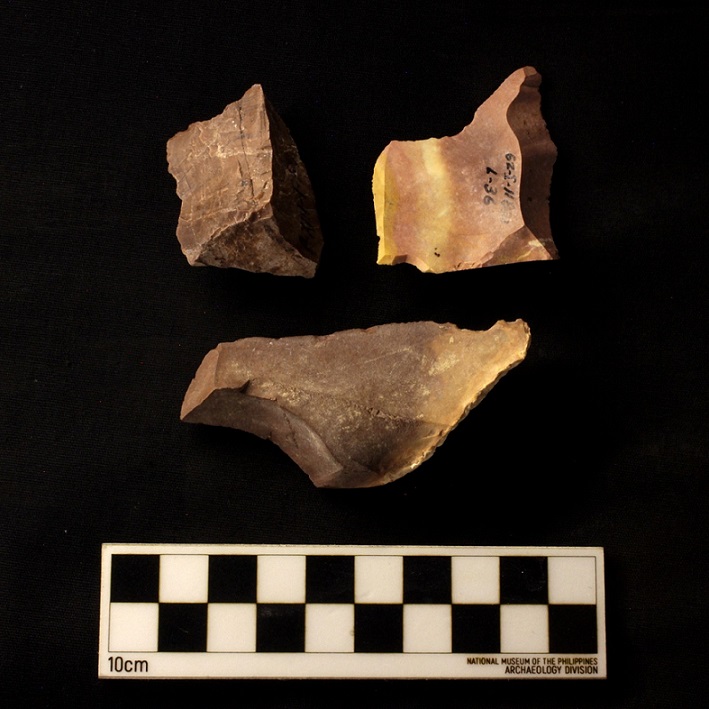

The study analyzed marks and striations on three stone tools discovered in the late Pleistocene site of Tabon Cave, Palawan. It reveals wear-and-tear patterns characteristic of thinning plant fibers. Microanalysis of the artefacts also reveal the presence of plant residues, whitish and fibrous, in the notches and markings of the stone tools.

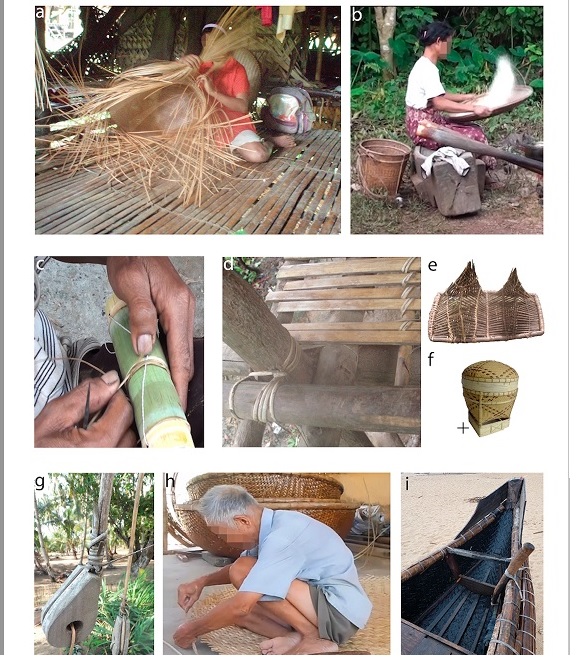

The Pala’wan people

To provide ethnographic context, the research team conducted fieldwork among the Pala’wan indigenous communities in Brooke’s Point, Palawan who use wild plants from the forest in their everyday lives.

One of the Pala’wan people’s most frequent activities is the processing of plant fibers into supple and flexible strips for making baskets and for tying materials. They also make bamboo knives and perishable containers out of vines and leaves, and extract hearts of palms (ubod) for food.

They use erect bamboo culms, bamboo vines, stems of bamban (Donax canniformis), leaf petioles or stalks of palms to make weaving strips for basketry and traps. Different kinds of rattan stems and the stem-like leaves of a creeping fern are made into tying materials.

Weaving strips are used to make basket-containers of different shapes and sizes, rice winnowers, and traps. Rattan tying materials are used to assemble and hold together the different parts of houses (posts, beams and flooring) and objects.

Experimental tools

The team meticulously replicated these plant processing techniques using experimental tools made of radiolarite or red jasper stones, quite common in Tabon Cave and other Late Pleistocene (c. 2.58 million to 11,700 years ago) and Early Holocene (11,700 to before 2000 CE) sites of the area.

The experimental flakes, replicas of the original Tabon Cave stone tools, were used to thin parts of plants from five different species: erect bamboo, bamboo vine, rattan, arenga palm, and bamban.

Similar use-wear patterns have been observed on the experimental tools used for thinning plants. The team has successfully reproduced the characteristic pattern of the microscopic wear-and-tear found on the three stone flakes from Tabon Cave. Moreover, the residues found on the artefacts correspond to the residues on the experimental tools.

In making strips for weaving and tying, several stages include: 1) obtaining the appropriate plant segment from the forest; 2) splitting the plant segment; 3) and thinning. By removing the inner layers of fibers, thinning turns the rigid plant segments into supple strips for tying or for weaving baskets.

Nowadays, the technique of thinning plant fibers is widespread among other indigenous groups in Palawan, as well as in farther areas in Northern Luzon, Batanes, Borneo, Southern China, and Laos.

Prehistoric knowledge

The study suggests that the technology of processing plant fibers and manufacture of cords, weavings, and basketry already existed 39-33,000 years ago in Southern Palawan. The oldest evidence of plant materials in the area were 8,000 -year-old fragments of a mat in Zhejiang, China.

The plant strips may have been used as tying materials to make baskets or traps, as the Pala’wan communities practice at present, or for some other purposes. Strings and cords can be used for bead or shell ornaments, and for complex activities such as bow hunting.

The manufacture of ropes, nets, and basketry are “technologies fundamental for navigation” in maritime environments. Fiber technology was a basic requirement for fishing using hooks and nets. Archaeological evidence for fishing practices in the Late Pleistocene has been found in Mindoro.

The human groups who lived in Tabon Cave had developed a deep botanical knowledge to know which plants around them “had fibrous, flexible, and solid properties, and could be turned into ropes, baskets, and other fibrecraft.”

As H. Xhauflair of University of the Philippines’ School of Archaeology says, “Fiber technology is extremely important. It allows making not only baskets and traps but also ropes that can be used to build houses, sail boats, hunt with bows, and make composite objects.”