THERE was a time — two generations ago — when Filipinos deeply loved their country and knew how to fight for their motherland’s freedom because it was the right thing to do.

The year was 1944. It had been two years since 100,000 Filipino and American troops in Bataan and Corregidor surrendered to an invading Japanese army. Filipinos have been waiting for General Douglas MacArthur to fulfill his famous “I shall return” pledge and liberate the Philippines, then a US colony. Over 200,000 guerrillas have been working behind enemy lines, continuing the resistance.

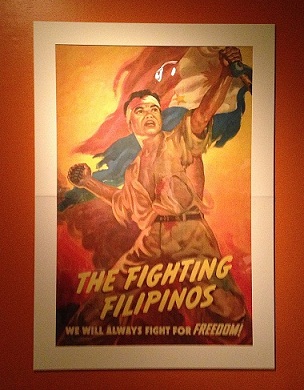

To keep the Filipinos’ spirits up, the Philippine commonwealth government, in exile in the United States, commissioned a poster. The task fell on a Filipino immigrant, Manuel Rey Isip, who left the Philippines in 1925 and settled in New York City. A talented artist, Isip drew illustrations for newspapers and movie posters for Columbia Pictures and 20th Century Fox.

The result was a propaganda poster, measuring 27 by 41 inches, that would make Isip famous. It depicts a wounded Filipino soldier about to hurl a grenade. With his left hand he holds aloft a Philippine flag — tattered but defiant — with the red field up, signifying that the country is in a state of war.

Fifteen thousand copies of “The Fighting Filipinos” poster were smuggled into the Philippines. It was quickly welcomed, especially by guerrilla groups, for it embodied the Filipino spirit of freedom.

Lopez Museum curators Ethel Villafranca and Ricky Francisco initially planned an exhibit to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Manila and the end of World War II. Then they realized that the museum’s collection had so much more to share. “We discovered that our nation’s history can be categorized according to different types of propaganda,” says Francisco.

These days, think of the word “propaganda” and you’ll most likely associate it with lies, deceit and politicians. But a long time ago, the word didn’t have a pejorative definition — and, in fact, it was very much a part of Philippine history.

In 1872, Filipino emigres in Europe formed a literary and cultural organization, El Movimiento de Propaganda (The Propaganda Movement), to lobby Spain for reforms in its sole Asian colony. Among its famous members were Jose Rizal, Marcelo del Pilar and several others.

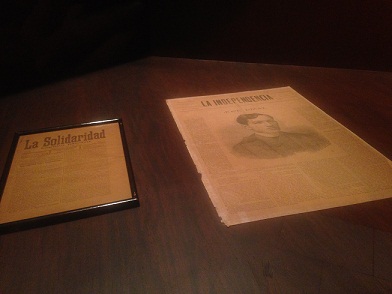

In 1889, they launched a biweekly Spanish-language magazine, La Solidaridad (Solidarity), which became the organ of the lobby group. Before the bolo and the gun, the pen was the instrument of democracy.

A rare copy of La Solidaridad is currently on display at the Lopez Museum, which is part of an exhibit, simply named “Propaganda.”. The exhibt runs until May 30.

Beside the magazine in a display case is a Spanish-language newspaper, La Independencia (Independence), a brainchild of Philippine Army chief General Antonio Luna, a member of the Propaganda Movement and one of La Solidaridad’s contributors before the Philippine Revolution.

Launched shortly after the Philippine declaration of independence in 1898, La Independencia was envisioned by Luna to help mold the new nation via hearts and minds. The paper was the most prominent among the nascent Philippine press.

Among its staff was soldier and writer Jose Palma, who wrote the original Spanish lyrics of the Philippine national anthem, published in La Independencia on September 3, 1899. Another staffer would gain immortality, academician Epifanio de los Santos, better known to Filipinos today by the initials EDSA, the main Manila highway that bears his name.

Inspiring as it may seem, what Villafranca and Francisco want from visitors, however, is for them to leave with another kind of inspiration. Whatever the forms of propaganda throughout Philippine history, as the two have discovered, the common message is that it is often about freedom from ills afflicting Filipino society.

“Research for this exhibit was a little bit hard emotionally because it was a reminder that we are just going around in circles,” says Villafranca. “It’s history repeating itself. It feels that we don’t learn from our history.”

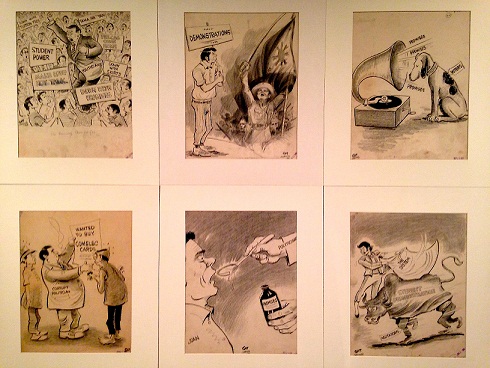

Villafranca makes an example of a collection of editorial cartoons, published in the 1960s by the now-defunct Manila Chronicle newspaper. An arch critic of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos, the Chronicle was shuttered by the government in 1972 after Marcos declared martial law.

Depicted in the cartoons are some of the headaches that are very familiar to Filipinos today, such as corruption and politicians making empty promises. “Take a look at the editorial cartoons. If you remove the dates, you’d think that they were drawn only yesterday,” says Villafranca.

That the struggle for the nation’s destiny began in the hearts and minds of Filipinos with the Propaganda Movement was no wonder. As much of the population in his day was uneducated, Rizal once concluded that the Filipino intelligentsia like himself, the ilustrados, should run the country some day.

And the battle for hearts and minds continues to this day.

With the 2016 presidential elections nearing, Francisco and Villafranca urge voters to be discerning for the sake of the nation amid the barrage of propaganda that characterize Filipino politics.

“We could see that a lot of problems facing the nation 100 years ago are still the country’s problems now. We’re hoping that it’s not a hopeless situation,” says Francisco. “Of course, there have been a lot of changes. We have more freedoms today — and hopefully people will use those freedoms to create change.”