By JOHNNA VILLAVIRAY GIOLAGON

TUKANALIPAO, Mamasapano – The old woman sat gravely in a corner of an unfinished classroom in Mamasapano town as an officer from the regional government explained that her group will be receiving complimentary health insurance.

Her head was covered with a maroon hijab, the bright color belying the sorrow in her eyes.

The woman’s son Rasul Kamsa had been one of 18 Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) fighters killed when police commandos launched a raid to arrest Malaysian terrorist Zulkifli bin Hir alias Marwan last Jan. 25.

The free health coverage being given to families of the slain MILF will cover them for the duration of the current administration. The renewal of the insurance will depend on the next administration and to the peace and order situation in this farming village.

The sound of gunfire has been silent in Tukanalipao for exactly a month now but what continues to ring loudly in residents’ ears is the tragedy of the deaths caused what is coming out as a seriously flawed police operation.

Kamsa’s death is particularly difficult for his mother, who requested her name not be published.

The 18-year old Kamsa was killed a day after a ceasefire was laid down between government security forces and the MILF 105 Base Command.

He was one of four men sleeping inside a makeshift mosque when PO2 Christopher Robert Lalan, the sole surviving member of a SAF unit, opened fire.

“(Kamsa) was in plain clothes. He was not armed,” sighed Kamsa’s 48-year old mother, who requested that her name not be published.

Lalan, in media interviews, maintains that he engaged armed MILF combatants.

Kamsa’s mother insists otherwise, pointing out that the boy “didn’t even join the fighting the previous day.”

She said that Kamsa stayed home on the day that fighting broke out in the cornfields half a kilometer away.“He takes his responsibility as the man of the house very seriously,” she said.

Hardly more than a boy, Kamsa had taken upon himself the duty of providing for the family, especially for his four younger sisters.

Kamsa tended the farm because his father was sickly. He also did the heavy housework like chopping wood and even chores usually done by girls in the family like cooking.

That is why a day after the fighting – and thinking that danger had passed – Kamsa set off early to check on the cornfield. It was just about harvest time; he wanted to check if fighting the previous day damaged the crops.

His family’s farm was beyond the banana grove just minutes walk where the SAF blocking force engaged the MILF.

Around mid-day, Kamsa settled down with neighbors Omar Dagados, Ali Ismail, and Musib Hashim inside the nearby mosque for a nap.

The small mosque where farmers hold daytime prayers is an open hut with a thatched roof and walls. The 10-square meter hut had a cement floor, half of which was covered with faded blue linoleum. Banana trees shielded it from the intense noonday sun.

Kamsa’s dried blood still stained the floor.

Ismail’s 32-year old sister said her brother’s death is a great loss not only to their family but to his fiancée.

Ismail was set to get married in March after his girlfriend finishes her working contract in Kuwait. The couple had been saving money to start their own family since getting engaged two years ago.

“Since our mother died years ago, he’s been helping our father with the farm and in managing the house,” she said sobbing.

Ismail joined the MILF at 23 years old. His sister believes that he was inspired by relatives and neighbors who have been keeping watch over their community.

Asked what form of justice she expects for the death of Ismail, his sister gave a confused stare.

She only said that what is important is for the tragedy not to happen again so that civilians like her wouldn’t suffer the heartbreak of losing a loved one in the same manner they lost Ismail.

Residents remember the day of the clash distinctly.

Policemen had begun converging along the one-lane highway the night before. They sensed something was going to happen but didn’t know what.

So as not to get in the crossfire, MILF fighters marched away from the main road where they lived and deeper into the interior of the barangay where the fields are.

It was very dark and quiet as a group of about 10 MILF fighters made its way over the wooden bridge and across the river, not knowing that a SAF unit planted itself in the cornfield on the other bank. They MILF planned to wait it out until security forces had left.

The men were crossing the bridge – logs and bamboo poles tied together and propped up by stilts – when the SAF opened fire.

Two were hit in the first volley of fire and fell into the cold water below. Their companions returned fire, now knowing who were attacking them from behind the cloak of night.

“The gunfire attracted attention and the others came to help. These are their relatives, their friends, and they were under attack,” village leader Jojo Apdal explained how the firefight quickly escalated.

“It was misfortune on their (SAF) part because they were outnumbered. Of course they were outnumbered because the MILF live here.”

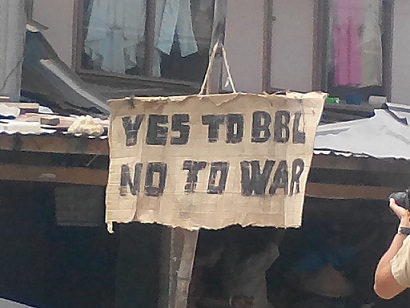

Apdal said MILF fighters are angry at being blamed for the death of 44 SAF commandos.“They (MILF) were attacked and now they are being blamed…Now, it is affecting the possibility of passing the (Bangsamoro Basic Law),” he said.

Apdal insisted, though, that residents still view the police – except for the officers directly involved in planning the operation – as keepers of the peace.

“When the time comes that the Bangsamoro government is in place, that (safeguarding peace and order) will be our responsibility,” he said. “And we will make sure we do it adequately.”