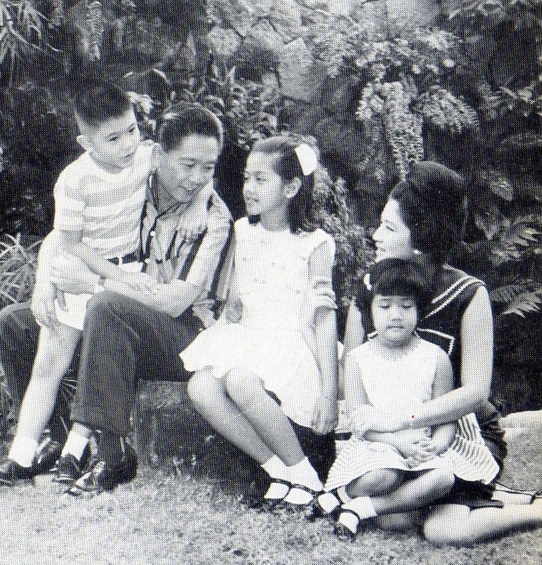

Filipinos witnessed the ouster of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and family from power and their flight from the Philippines in 1986. Filipinos also saw the family’s return from exile in the 1990s and the election of Ferdinand Marcos Jr. as president in 2022, his electoral campaign repudiating the terrors of martial law and the family’s ill-gotten wealth.

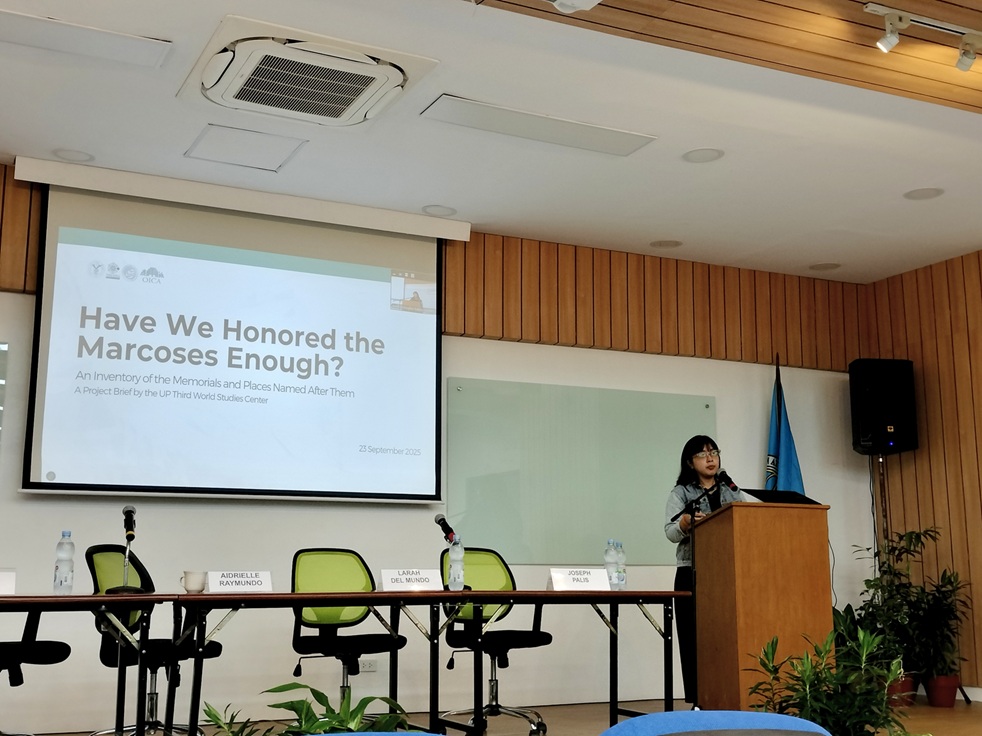

It was as if they never left, with sites exalting their “lineage and achievements” scattered throughout the country. A total of 250 sites have been catalogued by the project “Have we honored the Marcoses enough?” of the Third World Studies Center (TWSC) at the University of the Philippines Diliman. The project falls under the Marcos Research Regime program, which documents the permanent sites, structures, and objects commemorating the Marcos and Romualdez families.

The inventory started in Metro Manila and Luzon in 2023, expanding in 2025 to Leyte and Samar where a total of 150 sites were visited. A digital map of the sites are on the ArcGIS StoryMaps webpage (diktadura.upd.edu.ph), which was launched at the lecture “Home is where the loot is: Myth-making and memorializing in two Marcos mansions” on Sept. 25 at Pilar Herrera Hall of UP Diliman’s College of Social Sciences and Philosophy.

TWSC director Soledad Natalia Dalisay said the lecture was intended to start the critical discourse on the Marcos influence in spaces conduit to remembering them. The focal points were Malacañang of the North (aka Balay ti Amianan) in Paoay, Ilocos Norte, and the Santo Niño Shrine and Heritage Museum in Tacloban, Leyte, which were constructed during the dictatorship and continue to influence the people’s perception of the family.

The speakers were Aidrielle Raymundo and Arriane Fajardo, TWSC researchers, and Larah del Mundo and Joseph Palis, UP Diliman professors of history and geography, respectively.

Map discourse

In his lecture “Hiding in Places — Mapping Memorializations,” Palis discredited the definition of maps as graphical representation of the Earth, which he learned from his ROTC commander in his university days.

“Maps are never neutral,” Palis said. “They’re created by people who give you their version of something. Maps are like stories, [framing] and [giving] order to a story for humans. A map is an ongoing, dynamic, and incomplete story that will change and become a continuation.” (In an old lecture to high school students, he said, he described maps as lies and products of colonialism.)

Palis pulled up some maps of cartographer Denis Wood, who had said “a map is a proposition in graphic form.” One map showed Jack-o’-lanterns in Boyland Heights, Northern Carolina, which, according to Palis, “tells about ethnicity [and] people who practice Halloween and who don’t” and “also presents the class or those who can afford Jack-o’-lanterns.”

In the Philippine context, the mapped spaces of the Marcos sites are not innocent location markers but show the “politics of representation,” Palis said. He went on to explain that the “shrines, monuments, the Presidential Car Museum [and] Libingan ng Mga Bayani all encrypt legitimacy and preserve stories, [leaving no room] to question them.”

Palis juxtaposed the Marcos family and the slain revolutionary Lorena Barros to show the stark differences in historical narratives. He said there are grand memorials for Marcos Sr. and none for Barros except for a nondescript one at UP Vinzons Hall that will be demolished soon.

With maps becoming weaponized, Palis called for “flipping the script to memorialize those who should be memorialized.”

Seat of power

Del Mundo said she went on “The Great Marcosian Pilgrimage” upon returning to Ilocos Norte in 2023, visiting the Edralin ancestral house, Sarrat Central School, Ferdinand E. Marcos Presidential Center (FMPC), and Balay ti Amianan, “the fabled seat of power in the North.”

“Taken together, they trace the arc of [Marcos Sr.’s] life — from birth to presidency, which offers us a carefully curated spectacle of his and his family’s legacy,” she said.

Del Mundo said Marcos Sr.’s childhood and his mother Josefa Edralin Marcos’ extraordinary motherhood are rendered with the reverence of hagiography in the Edralin ancestral house, while Sarrat Central School hypes him up as respectful of life — supposedly refusing to kill even an ant. In the FMPC, she said, he is presented as a war hero “performing feats against the Japanese” who marries “the radiant Imelda from the South.”

Balay ti amianan

And, she said, Balay ti Amianan is the sanctum and domestic stage where the Marcos family is cast as rulers and benefactors of Filipinos. She said it projects the family as descended from Spanish aristocracy — an illusion, she pointed out, that was shattered by the fact that Marcos Sr., a congressman then, took out a loan from the GSIS (Government Service Insurance System) to build their San Juan residence.

Del Mundo said the Balay ti Amianan is mostly “a shrine to a carefully composed legacy — part museum, part myth, wholly performative.” She said it was called the Spanish mansion by Malacanang insiders in the 1970s, and is filled with grand paintings including the oversized portraits of Ferdinand and Imelda hanging in the sala mayor which, she remarked, “evoked the iconography of British monarchy’s coronation paintings.” She said an enormous portrait of Marcos Jr. in his room depicts him as a prince on horseback holding a Philippine flag in one hand and a book in the other — “a vision at once theatrical and messianic.”

Glorified achievements

The mansion’s other rooms are varied exhibition galleries, Del Mundo said. In the “Diplomacy” exhibit, the government’s principle of enlightened diplomacy is framed as a modern echo of indigenous Filipinos’ precolonial participation in Asian maritime trade networks.

The “OFW” exhibit presents labor migration as Marcos Sr.’s solution to the country’s dollar deficit during the 1970s petrocurrency crisis. Del Mundo said the deployment and exploitation of Filipinos abroad are reimagined as a patriotic contribution to nation-building, Marcos Sr.’s justification being that before the Spanish conquest, Filipinos moved within islands, even relocating overseas for safer areas of habitation, commerce, food and livelihood.

In the “Nation building” exhibit, Del Mundo said, the Filipinos’ origin story continues as a narrative suggesting that the Marcos Sr. government sought to unify the archipelago through concrete and steel, like the Austronesian forebears who once traversed a submerged world. She said it ties the narrative’s premise to Marcos Sr.’s 1965 campaign slogan “We shall make this nation great again,” cherry-picking elements from precolonial narratives and material culture to fashion them into symbols of supposedly noble lineage — i.e., the Maharlika class.

But the term Maharlika exposes the pretentiousness of Marcos Sr.’s act because it refers to a lower aristocracy rendering military service to a datu, Del Mundo said, citing William Henry Scott’s report of Juan de Plasencia’s account.

Controversial ownership

Del Mundo traced Balay ti Amianan’s dubious and litigious history. Built in 1977, it was Ferdinand’s gift to Imelda, which aligned with the regime’s Ilocos Norte Economic Agenda that sought to elevate “seats of power” as tourist attraction. Despite the unclear ownership, Del Mundo said, Marcos Sr. had an agreement with the then Philippine Tourism Authority in 1978 to develop the property for ₱1 a year for 25 years, after which it reverts to the Marcos family.

With the lease’s expiration in 2003, according to Del Mundo, Marcos Jr., acting as estate executor, demanded the property’s return and payment of rental fees in 2005. He called for the sub-lessors to vacate the property, triggering a string of litigation in 2007, she said.

Per Del Mundo’s account, the Sandiganbayan ruled against Marcos Jr.’s claim over the land in 2014. The Supreme Court invalidated his claim in 2024, ruling that the land on which the mansion stands is public property and part of the ill-gotten wealth, and that the 1978 lease is unconstitutional. But despite these rulings, the mansion is still used to propagate the Marcos narrative, Del Mundo said, referring to a 2024 virtual tour in which Sen. Imee Marcos played up the Ilocano character of her and her sister Irene’s bedroom, pointing to a lakasa (wooden chest) containing their abel (woven fabric), etc.

Del Mundo questioned the senator’s claims, arguing that Balay ti Amianan was built for tourism and that the family mostly used it for their parties.

Luxurious shrine

Raymundo and Fajardo discussed the Santo Niño Shrine and Heritage Museum, another gift of Ferdinand to Imelda, and one of more than 20 presidential mansions built during martial law. It was constructed between 1979 and 1981 where the Quonset hut of the Romualdez family once stood. The shrine was sequestered by the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCCG) in 1986 as part of the Marcos family’s ill-gotten wealth and later opened to the public as a museum. In 2023, Imelda and Irene Marcos’ claim to the property was nullified by the Sandiganbayan.

To explore the shrine-museum, Raymundo said, it is mandatory to have a tour guide. She said the ₱150 entrance fee is inclusive of the fee for the guide, who guarded against theft or damage to the shrine’s treasures and explained the supposed provenance of Imelda’s collections of paintings, statues, antiques, and religious artifacts, except for how she acquired them.

Raymundo said the shrine-museum is not a home but a spectacle of wealth projecting the Marcoses as cultured and aristocratic. There are seven rooms for the Marcos family, one for Fabian Ver (Marcos Sr.’s commanding officer of the Armed Forces of the Philippines), and 21 guest rooms showcasing Imelda’s achievements and Filipino culture, and dioramas detailing phases in her life.

According to Raymundo, Marcos Sr.’s room has a library while Imelda’s has large mirrors, a pink vase, a bathroom with a painted backdrop of a tropical sunset, a jacuzzi, and a salon chair. Marcos Jr.’s room has his report cards and his sisters’ bedrooms have “little chandeliers.”

“It was trying to look familiar, but it was only performative,” she said. “It’s more personal than Malacañang in the North as it evokes someone having lived there, except for the PCGG inventory stickers [serving] as tangible reminders of the origin of their wealth.”

Fajardo, Raymundo’s co-presenter, talked about what she called the “religious spectacle of the Marcoses.” At the shrine’s center is a chapel of the Santo Niño, which, as Fajardo put it, projects the “grandiosity of their religiosity, neutralizing their excesses [and] legitimizing their power [through] religious co-optation.”

A huge bas relief of the “Malakas at Maganda” folktale that confronts tourists is, Fajardo said, central to Marcos Sr.’s propaganda of destined leadership. A gigantic mural of a godlike Marcos Sr. and Imelda looking at the people completes the scene.

Fajardo summed it up: “[The shrine] is a ritualistic continuance of their family, a symbol of hope for the passive spectators where the public and private spheres are blessed in the domestication of the Marcos life and legacy.”

Whose history?

History is bifurcated in the Philippines. One force advocates for a history of resistance against injustice and oppression, and the other advances history based on a twisted perception of a family’s supposed greatness and on historical revisionism. Why, a young Filipino might ask, understate colonialism and the fight against it when Philippine history is grounded on resistance and struggles for independence? But history continues to be muddled with the Marcos family’s memorializing of their “magnanimity” through museums, government buildings, houses of worship, schools, etc., strengthening the myth-making.

The words of French historian Pierre Nora echo loudly: History is an intellectual and secular production, with a goal of analyzing and critiquing the past. In expressing agreement, Del Mundo said the grand structures honoring the Marcos family must be interrogated to understand how their legacy is being staged. She said Balay ti Amianan should stand as a testament to greed and excess, not as a monument to supposed glory.

Similarly, Raymundo encouraged Filipinos to “go visit and study how [the structures ] shape Marcos’ legacy and how to question [them].” Palis emphasized that in viewing the Marcos memorials and “the storying of their lives,” Filipinos’ “continued resistance and firm vigilance to historical revisionism must always be present.”