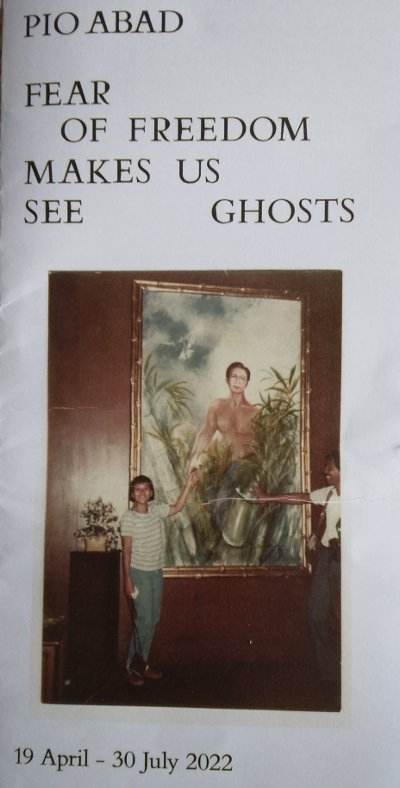

Fear of Freedom Makes Us See Ghosts is major solo exhibit of Pio Abad (b.1983) at the Ateneo Art Gallery, examining the conjugal dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos (1965-1986) through their hoard of valuable objects. It runs until 30 July 2022. Entrance is free and by appointment only.

At the exhibit entrance, a play on dissonance: a portrait of Ferdinand Marcos framed in pink hangs on a pink wall bordered with velvet curtains. A set of ornate furniture with cushions and a carpet, all in hues of pink, completes the scene.

In the first room, a stark sculpture of Malakas and Maganda, handformed in concrete and steel, looks forlorn and abandoned.

Two frames, all blackened, represent the replica portraits of Imelda as Maganda and Ferdinand as Malakas, painted over in black, after November 28, 2016 when the Supreme Court allowed Ferdinand Marcos to be buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani.

Shortly after the 1986 Revolution, the portraits of the Marcoses as Malakas and Maganda were put on display at the Malacañang Palace Museum. In 2012, Abad commissioned their replicas.

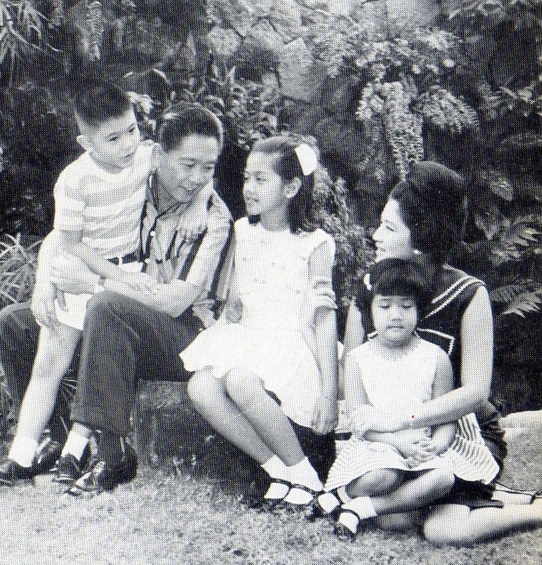

A creation myth in Philippine folklore, the Marcoses co-opted this myth in the 1970s and anointed themselves as “the strong one” and “ the beautiful one” under “the new society.”

And “the process of remembering through remaking” became central in Abad’s art practice. In his words, the greed of the Marcoses is so astonishing that it is often referred in collective terms as loot, plunder, or ill-gotten wealth that has also become so abstract in people’s minds. Abad’s installation projects seek to concretize and materialize specific objects accumulated by the Marcoses and confront the public with the reality of “its unwieldy scale and terrifying range.”

The Collection

Four sets of installation are displayed: ink drawings that depict objects from the Samuels Collection; postcard reproductions of Old Master Paintings; giclee prints of silverware; and 3D printed jewelry.

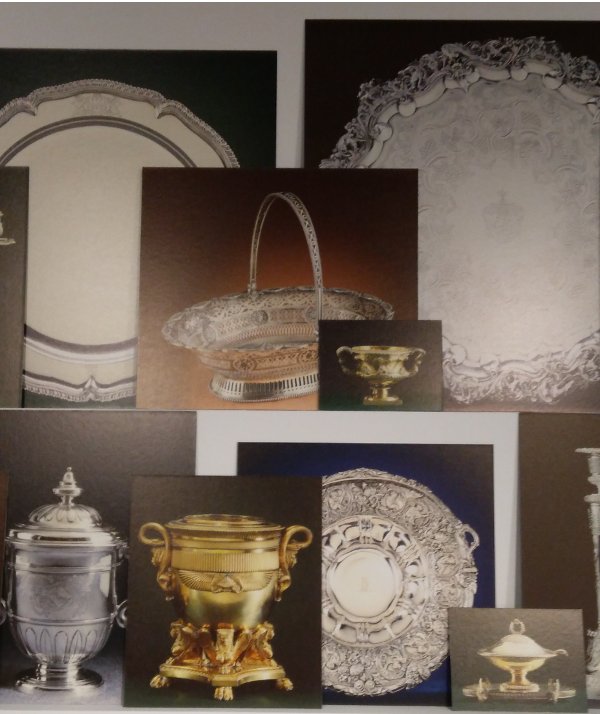

Silverware

Among the items left by the Marcoses when they fled the country are Regency-era (1811-1820) silverwares, sequestered by the Presidential Commission on Good Government in 1991. It included wine coolers, platters, tureen, candlesticks, and dinner plates and broke the record for the sale of silver ($4.9 million) by Christie’s in New York.

Abad reconstructs the collection as colored photographs in the scale of the actual silverware, based on images from auction catalogues.

Samuels Collection

In presenting intricate ink drawings of 23 objects from the Samuels Collection, Abad “not only traces the contours of their physical forms but also maps the narratives of dispossession contained within each artefact.”

An unknown buyer bought the entire contents of the apartment of philantrophist Leslie R. Samuels for US$5.95 million.

Shortly before Ferdinand and Imelda were indicted for fraud and racketeering in the US, the FBI, in October 1988, raided a property in Woodside, California owned by Gregorio Araneta III and Irene Marcos and recovered 113 items, and later identified as part of the Samuels Collection.

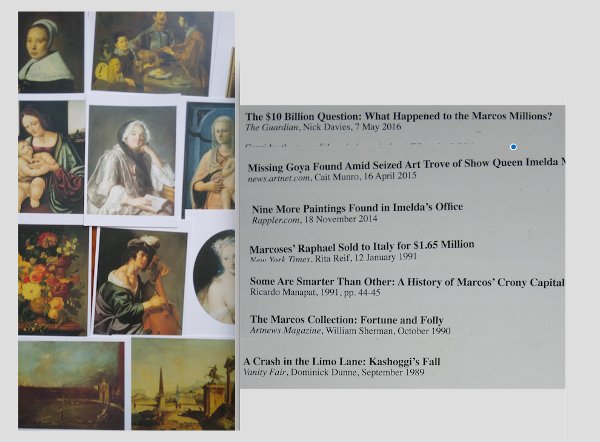

Postcards

This installation is composed of 90 different sets of postcards that depict Old Master paintings. News articles reporting on the Marcos’ ill-gotten wealth are reprinted at the back of each postcard. Printed in multiple copies, viewers may take some postcards, as an act of possession.

Jewelry

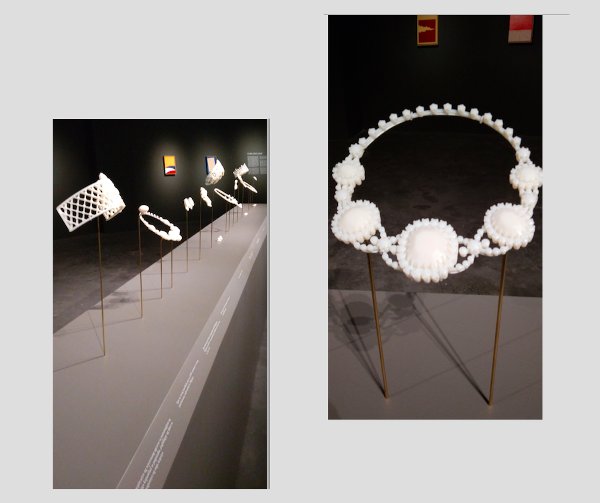

This iteration of The Collection of Jane Ryan & William Saunders consists of twenty-four 3D printed replicas of the jewelry brought by the Marcoses to Hawaii when they fled the country in 1986 and seized by the U.S. Customs in Honolulu.

Valued at US$21 million and known as the Hawaii Collection, it remains hidden at the Central Bank today.

Jane Ryan and William Saunders were the false identities used by Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos to deposit USD950,000 to bank accounts in Zurich, Switzerland in 1968.

A collaboration between Abad and his wife who is a jeweler, Frances Wadsworth Jones who digitally modelled each piece of jewelry, based on news footage and auction catalogues.

The off-white resin sculptures, stripped of all its glitter and color, was first exhibited at the Second Honolulu Biennial in 2019, returning 33 years later to the place where the Marcoses had fled. Like a spectre in its reappearance, the jewels carried with it “the painful history of a nation.”

Through the website www.janeryanandwilliamsaunders.com, the public can view the collection online and take ownership of the jewelry through Augmented Reality, and “imagining possibilities of restitution,” one day.

Counterpoint

Simply put, Abad’s installations— the ink drawings, silverware photos, jewelry sculptures— remain pleasing to the eye. Beneath the surface of prettiness, the reality remains that these real and specific objects represent a country’s plunder that remains unaccountable to this day.

The personal is political

Abad has focused a significant part of his art practice on remembering what has been forgotten or even expunged in the country’s modern history, especially the years of the Marcos regime.

He interrogates the line between historical truth and the large-scale fraudulence of the Marcoses amidst ongoing attempts to rewrite Philippine history.