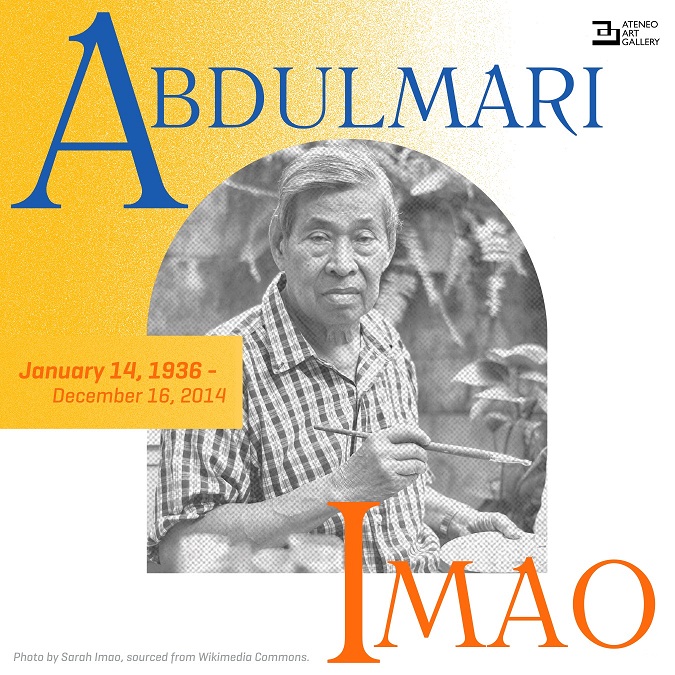

The month of January 2023 marks Abdulmari Asia Imao’s 87th birth anniversary. He remains the first and only Muslim Filipino National Artist in Sculptor, 2006.

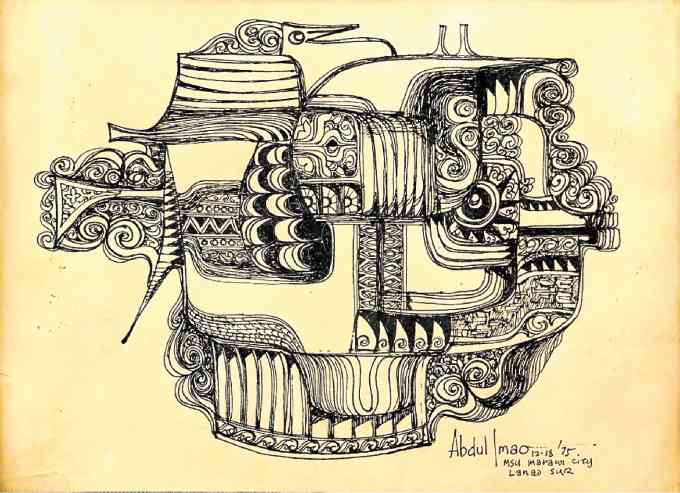

Drawing inspiration from the indigenous arts of his Sulu homeland, Imao incorporated traditional motifs of okkir into his own works—especially the sarimanok, naga, and pako rabong or fern motifs.

Ukkil/okkir, with its vine-leaf-tendril motif, is a major art form among the Muslims of southern Philippines, with the root word ukit, meaning “to carve.” With Hindu and Chinese influences that are especially seen in the naga design, a stylized form of the mythical dragon or serpent, and accompanied with leaf and ferns in spirals.

The art of southern Philippines is rooted in its indigenous traditions that have existed long before the spread of Islam, and expressed in its material culture such as woodcarving, architecture, boat building, grave markers, mat-making, and other functional and decorative forms connected with its way of life.

By incorporating okkir into his art, Imao revitalized the traditional form. More importantly, he raised the awareness of identity rooted in one’s place and geography to the larger Philippine society, as very much part of being Filipino, at the same time.

Sarimanok glory

The sarimanok refers to a mythical bird with flowing feathers and a fish in its beak, with many folk stories behind it.

Imao uses the sarimanok as the nexus of his visual world. His Sarimanok series (in acrylic or oil on canvas, in brass, relief on brass sheet metal, and print) are done in a variety of configuration that includes geometric and cubistic forms as well as vegetal design, with ferns tapering in graceful curls. His deconstruction of the sarimanok engages the viewers to trace where the bird begins or where the fish ends. Curvilinear and sinuous lines abound that echo the ebb and flow of the waves, undulating like the rise and fall of our lives.

The constants in Imao’s works include the use of vibrant colors (in shades of blue, green, yellow, pink, purple, orange), the red circle of a sun, the fish, the bird with rounded black eye and pointed beak, a bird’s tail of long flowing feathers that curls inwards, the fish scales with its mesmerizing curves, and an occasional dome of a mosque, a crescent moon, or a minaret.

He attributed his use of primary colors by being a fisherman for five years during the Japanese occupation where he saw so many colorful fishes. “ I was inspired by them, because of their color.” He added that in general, Tausugs prefer bright colors. “You’ll see that even their native costumes are very, very colorful; primary and secondary colors are their main color scheme.”

Abdulmari Asia Imao (1936-2014)

Amidst a most impoverished background, the young Imao sold ice drops, peanuts, and guinataan around movie houses in Jolo in order to stay in school at the Jolo Trade School, where he also carved furniture to augment his income. He also worked as a stone breaker in road construction, and as a cargador in the Jolo pier. He continued earning his keep in UP by working as a model and posed in life drawing sessions at the university.

Having no access to paper and pencil did not stop him from expressing his artistic urge. He drew on the leaves of dapdap and banana, drawing ukkil designs early on.

In 1969, in an interview with Nick Joaquin, Imao mentioned that he had been “working on the sarimanok style. This is a design I am trying to improve, revitalize. That is why I have been doing research on this Muslim motif: to develop it into another design which will be distinctively Muslim. ”

Education, fate, and fortune

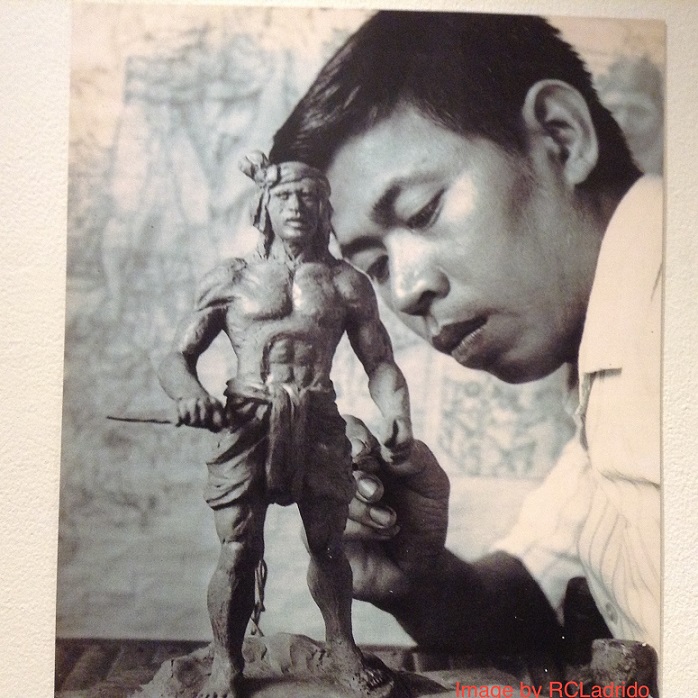

Seeing Philippine art on a floating exhibit in 1954 by the Arts Association of the Philippines aboard a ship in Jolo captivated so much the young Abdulmari that he visited it almost daily. Tomas Bernardo (1916-1994), a painter and the AAP secretary, noticed the young man’s keen attention to the exhibit and encouraged him to explore his artistic leanings in Manila. Eventually, Imao received a scholarship from the Commission on National Integration and studied sculpture at the University of the Philippines, under the guidance of Guillermo Tolentino, Anastacio Caedo, and Napoleon Abueva.

Several scholarships supported further his art studies: a Smith Mundt and Fulbright scholarship for a master in fine arts in sculpture, major in brass casting at the University of Kansas, 1960-1962. He did advanced studies in sculpture and ceramics as a Fellow at the Rhode Island School of Design from 1961-1962, and in brass-casting and photography as a Faculty Scholar at the Columbia University in New York City from 1962-1963. He was the first Asian recipient of the New York Museum of Modern Art Grant to Europe and Scandinavia in 1963.

Returning to the country in 1964, Imao taught fine arts at the University of the East. After receiving the Ten Outstanding Young Men Award in 1968, he decided to become a full-time sculptor and painter.