Images courtesy of the British Council, Woven Networks Project

The Woven Networks project tells stories of handloom weaving communities across the country and their interconnection with the land and the forest —the source of their livelihood. It includes weaving communities in Sierra Madre, Nueva Vizcaya, Bukidnon, Misamis Oriental, Samar, Leyte, and Cebu. It aims “to strengthen the voices of local communities by highlighting their sustainable practices and vital role as artisans.” Indigenous weavers also shared their stories and what weaving means to them, as part of their cultural heritage.

Supported by the Forest Foundation Philippines and the British Council through its Crafting Futures global program, the Woven Networks project presented the highlights of nine research grantees and their investigative work with craft communities.

See also From Land to Loom, From Fiber to Form, the virtual exhibition on weaving communities based on the Woven Networks project, curated by Tessa Maria Guazon. It runs until December 2, 2022.

(https://sway.office.com/cJQVDuQNVVcTwAb8?ref=Link)

Our weavers and artisans

Today, who are our weavers and artisans? Found in almost all parts of the Philippines, the weavers are part of an estimated 450 handloom weaving groups or a total of 5,000 individuals. Mostly women, many are members of indigenous communities. Now in their 60s and 70s, the master weavers try to pass on their knowledge to younger family members, but many are uninterested or reluctant to continue such tedious and labor-intensive work with low financial return.

Mostly working part-time, the weavers persist in weaving, as it is a source of income, however meager. Weaving as an economic activity remains far from being self-sufficient; while they do the actual work, weavers are the lowest paid at the bottom of the market chain.

Reliance on forests

The natural materials gathered and processed by weavers grow wild in the forests, in nearby areas and backyards, or bought. Such include tikog, yantok (rattan), bamboo, pandan, nito, buri, abaca, nipa, coconut shells and fibers, anahaw leaves, bark, and molave wood.

The end products are mostly familiar ones such as banig or mats (made of buri, pandan), baskets, tingkop baskets, bayong, bags, furniture (bamboo), home décor, fish traps, hats (salakot), fans, blinds, and the bilao or winnowing basket.

Based on United Nations figures, 25 percent of the world’s population relies on forests for their livelihood, 60 million of whom are indigenous peoples. Around 85 percent of the Philippine’s key biodiversity areas are within ancestral domains of indigenous communities.

Looking closely

The Rurungan sa Tubod Foundation surveyed craft communities in Palawan that include the Jama Mapun weavers in Bgy. Isumbo, Sofronio Española who makes pandan mats with intricate woven designs. In Bgy Oring-Oring, Brooke’s Point, the Takin Bawat Tipo, also Jama Mapun weavers who produce pandan mats made of two parts, the topside, and the back. The thorny variety or pandan baña is used for the topside, as it is thinner and easier to make into smaller strips for dyeing and design; the second type is pandan bacung, used for the back part as it is thicker and sturdier.

In Bgy. Samarinya, Brooke’s Point, Sublito Tiblak has been creating smaller versions of tingkop baskets. Without using any dyes at all, he makes use of the natural colors of different materials to create patterns in his products. He gets them from plants such as gahid (nito), ubaran (nito), buldung (a type of rattan), and busnig found in Mt. Mantalingajan, the highest mountain in Palawan.

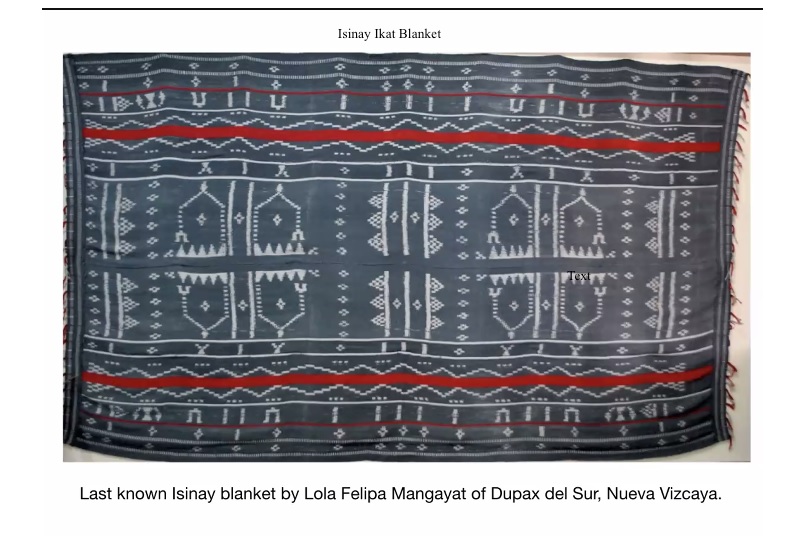

Isinay Ikat Revival

The Isinay was known for producing the finest indigo dyed ikat weaves. However, the tradition had disappeared with the Christianization of the Isinay. The last known Isinay dyed ikat blanket (uwes pinutuan, death or travelling blanket) is kept by the St. Vincent Ferrer Church, Dupax del Sur, and made by Felipa Mayangat Castillo in the 1980s.

Ikat weaving is a shared tradition among the Isinay, Ifugao, Ibaloy, and Kankana-ey speaking communities in Benguet and part of Mountain Province.

The project proponent, Patricia M. Araneta, aims to revive the Isinay ikat weaving tradition in Dupax del Sur, Nueva Vizcaya. Cotton and indigo, the main materials, need to be cultivated in the area, as a precondition for the revival of ikat weaving. The Isinay and the Ifugao communities are interested in growing organic cotton for their threads and indigo plants for their natural dyes.

Hinabol weaves

Hinabol, an abaca-based textile with colorful striped traditional design, is part and parcel of the Higaonon’s way of life, made by the Kalandang Weavers Group within its ancestral domain in Mintapod, Bukidnon. It is an important part of their rituals and gift giving (weddings, tribal gatherings, community peace talks), and a source of livelihood. The Higaonon practice of gift giving (sugot) maintains and strengthens social cohesion in the community.

Amidst demand for sustainable fabric, Hinabol weaving needs to be revived and strengthened in value and range of products. Wider use of natural dyes for hinabol is encouraged; some 18 types of natural dyes have been identified in the area.

Abaca does not require the clearing of forests, providing for a sustainable source of livelihood.