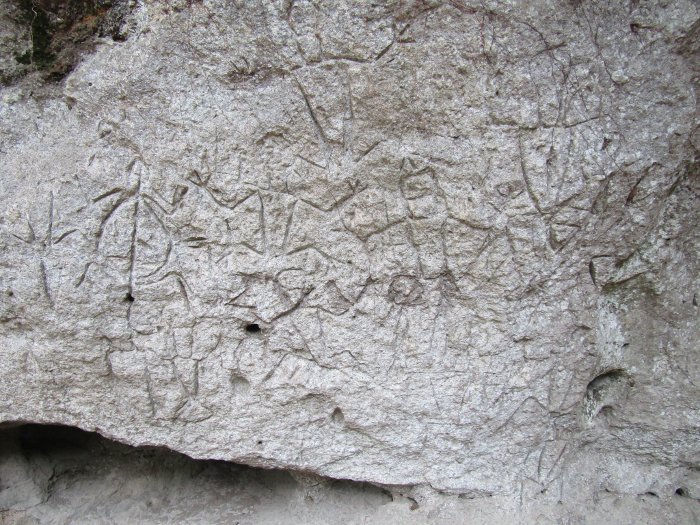

Angono-Binangonan Petroglyphs (National Cultural Treasure). Image courtesy of National Museum Philippines

With 22 known rock art sites in the country, the Angono-Binangonan Petroglyphs remains as the best-known site since its discovery in 1965. Some other sites, mostly archaeological, are found in Peñablanca, Cagayan; Anda, Bohol; Alab, Bontoc; and the Pälaqwan cave drawings in Rangsang, Palawan.

The National Museum defines rock art “as human-made markings on surfaces of immovable rock.” It is generally categorized as pictograms (paintings and drawings) or petroglyphs (engravings or carvings).

Recent findings on the Neanderthal paintings in Cueva de Ardales, Spain have confirmed that the creative impulse in our prehistoric ancestors is innate and it is not restricted only to modern humans, the Homo sapiens.

In short, cave paintings are imprints of a primal impulse to leave a trace of one’s existence, “We are here!”

A first in Southeast Asia

First directly dated human figure in Peñablanca Cave. Image courtesy of National Museum Philippines

A drawing of a human figure on a cave wall in Peñablanca, Cagayan has become the first directly dated rock art in Southeast Asia.

The figure has been directly dated as about 3,500 years old, based on samples of the pigment from the drawing using radiocarbon dating method.

“This date is older than anyone expected and it marks the beginning of the direct dating revolution in Southeast Asia, ” says lead author Andrea Jalandoni of Griffith University, Australia in a paper titled First Directly Dated Rock Art in Southeast Asia and the Archaeological Implications (Radiocarbon, June 2021).

Direct dating involves a process where the paint material from the rock drawing itself is dated, instead of dating the materials around or on top of the artwork.

Peñablanca pictograms

The rock art in Peñablanca, Cagayan are pictograms with drawings on the rock surface using charcoal. With more than 350 images documented, more than half are considered abstract and linear shapes, followed by leaf outlines, human forms, and animal images as documented by M. Faylona in a paper titled Re-examining Pictograms in the Caves of Cagayan Valley (2016), published in Rock Art Research.

Circleweb drawing, Peñablanca Cave. Image courtesy of the National Museum Philippines<

Human figures, leaf, and circle motifs have also been found in other sites in Southeast Asia.

The Peñablanca area has also been a prehistoric habitation and burial area where fossils of an early human species Homo luzonensis in Callao Cave have been dated to about 67,000 years ago.

Based on their data, Jalandoni and her research team also note that the rock drawings may have been early Austronesian or Agta, the Negritos in the area.

Angono-Binangonan Petroglyphs

Prehistoric images of geometric and human-like figures are engraved on the walls of a rock shelter in Angono, Rizal. The walls are made of volcanic ash deposit, fine-grained with brownish to yellowish color, called Guadalupe Tuff.

Close-up of Angono-Binangonan Petroglyphs. Image courtesy of National Museum Philippines

In 1977, Jesus Peralta of the National Museum examined the petroglyphs and found a total of 127 distinct images, mostly human figures.

In 2016, Andrea Jalandoni of Griffith University documented the Angono petroglyphs and used the Geographic Information System (GIS) to create a three-dimensional model of the site. As a result, 52 additional images have been identified to a total of 179 images, as discussed in her paper (2018) on the rock art of Angono.

Jalandoni has categorized the petroglyphs into two phases: the first phase is older, and composed mostly of geometric figures and vulva forms in oval or triangular shapes; the second phase is mostly composed of human-like figures that had been converted from the geometrics in the first phase by adding arms and legs. Other images consist of female genitalia.

Jalandoni described the vulva forms as “triangular shapes with a bisect line or hole/small cupule near the bottom of the triangle.”

Similar vulva form designs are also found in many parts of the world, mostly made by hunter-gatherers.

The petroglyphs have not been conclusively dated. The rock shelter itself was formed in the late Pleistocene or early Holocene period and the earliest time the Angono petroglyphs could have been made would be approximately 11,700 years ago, adds Jalandoni.

Alab, Bontoc

The Alab engravings were first reported in 1972 to the National Museum. Jesus Peralta of the National Museum estimated some 200 engravings of “pudenda and two penes.” Vulva forms and triangular forms predominate that locals refer as binut-butu or “clitoris-like.”

Anda Cave, Bohol

Red hematite hand prints, Anda, Bohol. Image courtesy of National Museum Bohol

Located in Lamanok Island, Anda, Bohol, the site is an open rock shelter facing the sea. The paintings are reddish hand stencils, with fingers, palms, and many other smudges. Made of red hematite, the pigment is produced by grinding iron ore from the earth.

Interpretations and threats

Through the years, archaeologists have proposed that prehistoric peoples created such drawings to mark a sacred space, a burial ground, hunting or fertility rituals, or narratives of their lives.

In the country’s rock art sites, many ancient markings have disappeared or are barely visible due to natural deterioration, weathering, water damage, or vandalism. Other human activities such as land development, mining, and farming also continue to threaten these sites.

At most, research on rock art sites in the Philippines offers only a baseline documentation of their existence before they are lost forever.