It has been three years since the extraordinarily barefaced development: a president firing a career government official of a constitutionally independent body tasked with anti-corruption functions, for disclosing details of his bank accounts.

A word has revved up in current political lingo that some wish to use as criterion for the 2022 elections: enabler. It has been three years since that scandalous event. Who were the enablers to that scandal? And more importantly, who had wrestled the enablers in behalf of the madlang pipol?

On July 30, 2018, Malacañang signed the dismissal order of Overall Deputy Ombudsman Arthur Melchor Carandang, who, it said, it found “guilty of graft and corruption and of violating the government’s code of ethics.” What actually precipitated it were two complaints filed before the Office of the Executive Secretary on October 3, 2017 by former congressmen Jacinto Paras and Glenn Chong, and by lawyers Manuelito Luna and Eligio Mallari.

The Paras-Chong complaint said Carandang allegedly disclosed to the public “illegal and unlawful disclosure records or bank transactions of the President and his family, which turned out to be falsified and spurious.” The Luna-Mallari complaint virtually echoed Paras-Chong as “disclosing details of their investigation” on the Duterte family’s bank accounts.

When asked by media, Paras said the disclosure of the bank accounts was a destabilization plot, and that Ombudsman Conchita Carpio-Morales was behind it. Luna, on the other hand, said the Ombudsman probe on the bank accounts was “an assault against the Office of the President.” Both offered no clues as to how this was an alleged “power grab.”

It took only one month for the Office of the Executive Secretary to finish its investigation, and then followed by the usual volley of outbursts from Duterte. The Malacañang report sounded partisan, saying Carandang was “guilty of manifest impartiality toward Senator Antonio Trillanes.” Trillanes was the first to expose the Duterte bank accounts, which had allegedly amassed 2.2 billion pesos.

The question is: What exactly did Carandang do that invited presidential lambasting? On September 17, 2017, in a reply to an ambush interview, Carandang confirmed that his office had obtained bank transaction copies from the Anti Money Laundering Council (AMLC) and – here’s the twist – they are similar to the copies of Senator Trillanes. AMLC, under an appointee of Duterte, denied the bank records came from it. But AMLC had also said the bank transactions it had seen were confidential, sounding instead like it had seen them, only that it refused to comment. And so, fury followed.

A Duterte tantrum, especially when shaming him triggers it, does not and will never end without vendetta. Malacañang dictated that the head of the constitutionally independent body, which at that time happened to be the unflinching Carpio-Morales, obey the Duterte order to sack Carandang. It wanted Carandang suspended for 90 days.

Carpio-Morales defied the order, saying the Office of the President had no disciplinary jurisdiction over the Ombudsman. Duterte threatened. Then she said the ultimate repartee: “Sorry, Mr. President. This office will not be intimidated.” And then the blunt but decisive irony: “If the president has nothing to hide, he has nothing to fear.”

Carpio-Morales won that argument, showing that rule of law succeeds over fascist fancy. Malacañang had to wait for the end of her seven-year term. The Palace was enabled to sack Carandang only after she had retired sometime in July 2018. Carpio-Morales, fierce defender of constitutional law, direct paternal aunt of presidential son in-law Mans Carpio, was no longer in office to use the might of taxpayers’ money to obstruct Duterte autocracy.

On November 26, 2020, Duterte announced Warren Rex Liong of Davao city as Carandang’s replacement. Let Liong’s curriculum vitae speak for itself: legal consultant of vice mayor Rodrigo Duterte August 2010-June 2013; resource person for the Duterte political party Hugpong sa Tawong Lungsod May 2004, May 2007, May 2010; appointed by Duterte to the board of directors of Philippine Reclamation Authority March 2017. Here’s what the CV does not say: he is Duterte’s fraternity brother in Lex Talionis.

Carandang was also slapped with accessory penalties of cancellation of eligibility, forfeiture of retirement benefits, restriction from taking civil service examinations, and perpetual disqualification from holding public office.

But what does Supreme Court jurisprudence say? In disobeying Duterte, Carpio-Morales cited a 2014 SC decision striking down Section 8(2) of the Ombudsman law or Republic Act No. 6770, which allowed the President to discipline deputy ombudsmen. That provision having no longer existed, the ouster of Carandang was unconstitutional and illicit, legal experts opined with Carpio Morales.

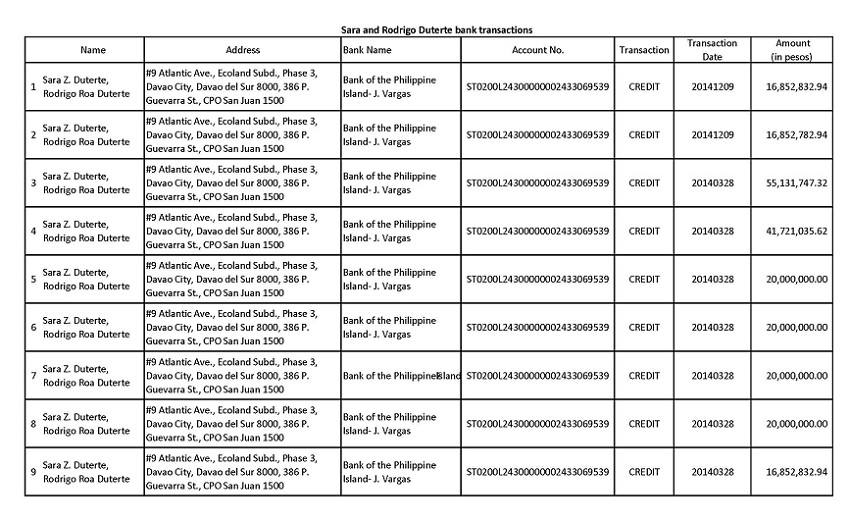

By the way, what were these bank accounts? Senator Trillanes first brought these to the attention of the public in April 2016, a few days before the May presidential elections. The transactions were betrayingly detailed. They pertained to multiple bank accounts of Duterte, the Duterte children, Honeylet Avanceña, and her daughter Veronica Duterte. They involved US dollar accounts, investment accounts, placement accounts, insurance policies, etc. The VERA Files study of the bank transactions showed they never tallied with the cash in bank (CIB) and cash on hand (COH) that Duterte and daughter Sara had declared in their Statements of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth (SALN).

VERA Files’ one-liner captured it all: if truth is not on your side, suppress it. To the point of defying law, jurisprudence, and the constitution, of being cantankerous at Carandang and Trillanes. The actions gave the message that the Dutertes may indeed have hidden wealth, that they possibly earn their wealth through ways that may not be above board, and that they would like very much to hide it. And when you talk about it, you may be targeted for a hate campaign (at the very least). In other words, Duterte wealth is Noli Me Tangere.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.