If truth is not on your side, suppress it.

That is what Malacañang is doing in the case of the undeclared wealth of President Duterte which was exposed by Sen. Antonio Trillanes IV way back in April 2016, less than two weeks before the May 9 elections.

Last Monday, July 30, Malacañang released the order signed by Executive Secretary Salvador C. Medialdea dismissing Overall Deputy Ombudsman Melchor Arthur Carandang from service after Palace investigation found the latter “liable for graft and corruption and betrayal of public trust.”

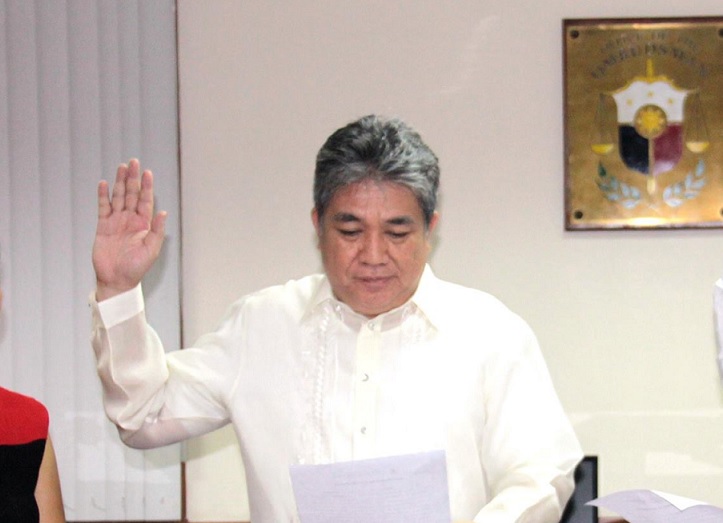

Overall Deputy Ombudsman Melchor Arthur Carandang

The investigation of Carandang stemmed from two cases filed against him: The first complaint by lawyers Manuelito R. Luna and Eligio P. Mallari and the other by Jacinto V. Paras and Glenn A. Chong.

The complaints cited Carandang’s media interview saying that the figures in the documents he received from the Anti Money Laundering Council about the bank records of Duterte were “more or less” the same as the figures in the bank records attached by Trillanes in his complaint against Duterte, his daughter Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte and his son, then Davao City Vice Mayor Paulo Duterte.

Medialdia said for his “transgressions”, Carandang is “penalized with dismissal from service which carries with it cancellation of eligibility, perpetual disqualification from holding public office, bar from taking civil service examinations and forfeiture of retirement benefits.”

There are many legal questions about Medialdia’s order. Number one is whether the President can remove officials from a constitutionally-created independent office.

It will be recalled that last February, Medialdia suspended Carandang for 90 days for the same reason cited in his dismissal but then Ombudsman Conchita Carpio-Morales refused to recognize the order insisting that Malacañang has no jurisdiction over her deputy.

In an interview with Carpio-Morales before her retirement last July 26, she said: “Well, if by refusing to implement the order of Malacañang, I protected him (Carandang) that’s it. But if there was any protection it was in account of the fact that indeed Malacañang is not having any jurisdiction over him, administrative jurisdiction over him.”

Former Solicitor Florin Hilbay’s opinion (“patently unconstitutional” ) on the 90-day suspension of Carandang applies to July 30 order of the President made through Medialdia.

Hilbay cited the 2014 Supreme Court decision in Gonzales III v. Office of the President is clear: The President has no disciplinary authority over a Deputy Ombudsman.

Hilbay said “The burden is therefore on the Executive Department to first seek a reversal of the prior judgment of the SC before acting inconsistently with that jurisprudence.”

Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque even dared the Ombudsman to question Medialdia’s order before the Supreme Court which was actually a trap knowing the pro-Duterte leaning of most of the justices. Carpio-Morales didn’t fall into the trap.

Hilbay further said: “Ombudsman Carpio-Morales acted correctly in rejecting the President’s order to suspend Mr. Carandang because she has the two-fold obligation of following the Constitution and protecting the independence of her office. The law is clear, she simply followed it.”

The release of the dismissal order is not unintentional. There is no Carpio-Morales to stand up to Malacañang to defend the independence of the Office of the Ombudsman.

That brings us to theother legal question of who and how will Medialdia’s order be implemented?Carpio-Morales retired July 26. Her successor, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Martires, has not yet taken his oath. The acting Ombudsman is Carandang.So, Carandang will dismiss himself?

Those bank documents that the President does not want AMLC to confirm are indeed devastating to him and his family. VERA Files analyzed it from the copies obtained from the Senate records and our initial investigation showed that the President and his daughter Sara omitted to fully disclose their joint deposits and investments at the Bank of Philippine Islands, which conservatively exceeded P100 million in some years, when they were mayor and vice mayor of Davao City, our analysis of bank records submitted to Congress and their annual net worth declarations shows.

According to the bank records, Duterte and Sara’s transactions with BPI, initially its Greenhills-EDSA branch and later the Julia Vargas branch, included:

• A P48.17 million placement in 2006 that grew to P55.13 million by 2013

• A P40.55 million investment in 2009 that stood at P41.72 million in 2013

• About $220,000, roughly P10 million, from 2006 to 2012

• The purchase of P80 million in insurance policies in 2014

• A P16.85 million investment begun in 2014

Our analysis showed that the amounts Duterte and Sara listed in their statements of assets, liabilities and net worth (SALN) as cash on hand (COH), cash in bank (CIB) and investments for these years are nowhere near the combined value of their bank transactions as reflected in bank records submitted to the Senate.

Duterte only listed from P6.07 million to P13.85 million a year in cash. He began declaring investments only in 2008, at first P3.65 million and later P3.8 million a year starting in 2011.

Sara’s cash declarations ranged from P2 million to P4.32 million a year from 2007 to 2012. She reported annual investments of from P1.93 million to P2.67 from 2008 to 2012.

The documents showed that father and daughter failed to declare from P44.25 million to as much as P85.73 million a year from 2006 to 2014.

The penalties for violating the SALN provisions in RA 6713 are imprisonment of up to five years, a fine of up to P5,000 or dismissal from the service. (Click here https://verafiles.org/articles/duterte-sara-fail-declare-p100m-investments-documents-show-1 for the full article.)

When Trillanes exposed Duterte’s undeclared wealth during the election campaign, the Davao city mayor, who presented himself poor and short of funds, dismissed the bank documents as “garbage.”

Garbage stinks. The foul odor can’t be surpressed. Lalabas at lalabas yan.