In the uplands of Mindanao, the women of the Erumanen ne Menuvu and Teduray indigenous tribes hold a belief as ancient as the land: if one eats, then everyone should get to eat.

This gave birth to a centuries-old traditional farming method in their homeland in Cotabato and Upi, Maguindanao del Norte that has outlived the grip of colonial strongholds in the Philippines. The method involves growing produce from seeds passed down through generations which has taken root in community farms cultivated and tended by women.

Marilou Taupan, or Missboy to her fellow Erumanen ne Menuvu, knows this tradition as Suragad, which is organic to its core. With this method, the tribe grows root crops, rice, fruit-bearing trees and plants in rotation without synthetic fertilizers to keep the land healthy.

For example, sweet potatoes and corn serve as reliable alternatives to rice, especially when rice farming is not in season. These also serve as natural protective barriers of upland rice from pests, Taupan said.

For Teduray women, the same practice is called Sulagad, according to tribal leader Jennevie Cornelio. The crops they grow are not sold for profit but go straight from the farms to the tables of every household in the community.

“Hindi namin pwedeng iasa yung kakainin namin sa gobyerno. Sa paniniwala kasi ng Erumanen ne Menuvu, walang magugutom na katutubong komunidad kung may tanim na Suragad,” Taupan explained.

Aside from providing food security in the community, Suragad/Sulagad organic farming practices also offer a path to reduce reliance on synthetic fertilizers.

This is why Cornelio and other women farmers go from village to village teaching young indigenous women the ways of Sulagad.

The ‘Toxic’ Legacy of Masagana 99

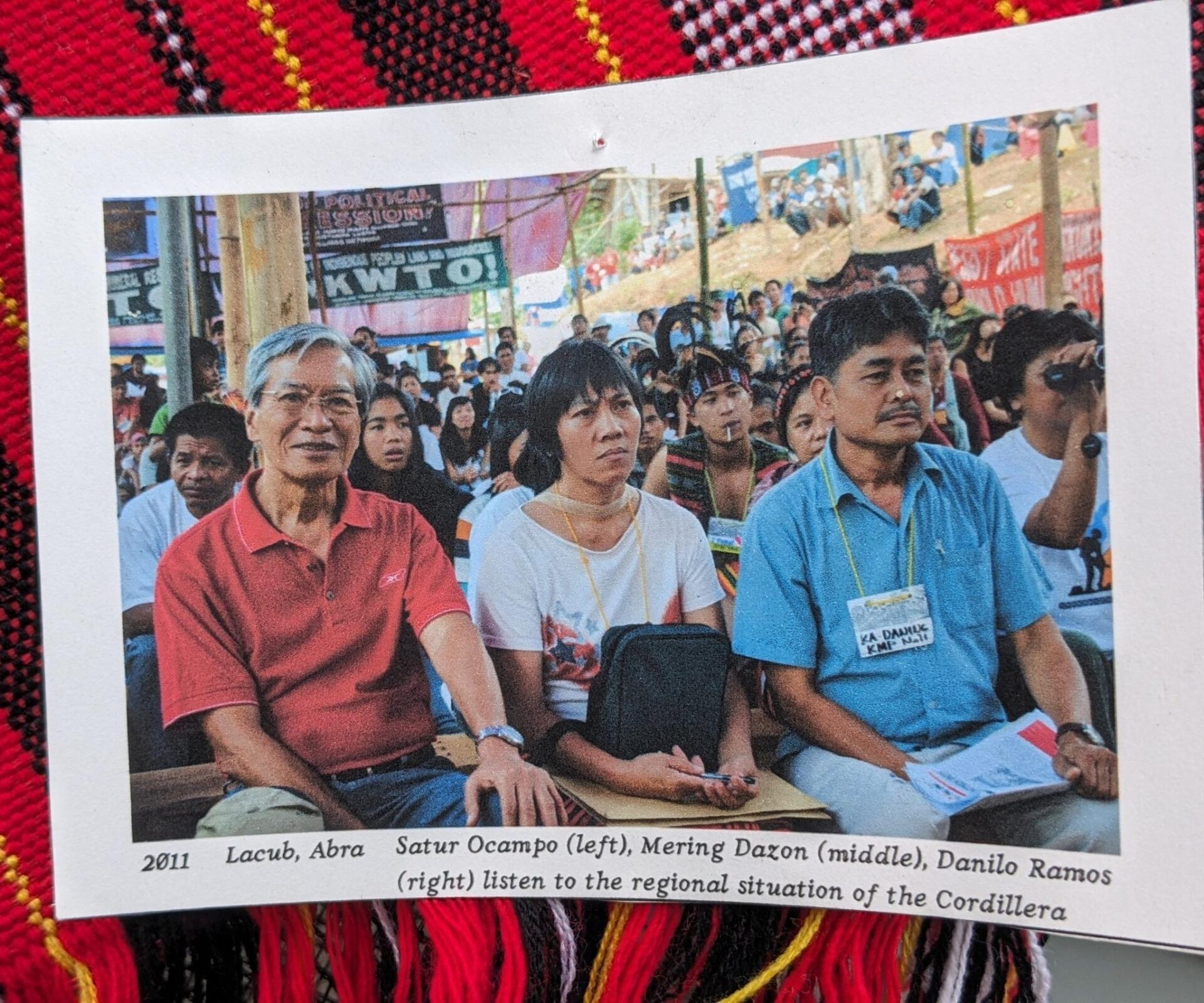

In the upcoming midterm elections, one senatorial candidate stands in solidarity with these women farmers in the struggle to keep these age-old farming practices alive. Farmer-activist Danilo “Ka Daning” Ramos is on a daring quest to bring to the upper chamber the issues against the use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides to finally stop agricultural practices that he says have long burdened the country’s farmers.

The wide use of these fertilizers is a remnant of a failed agricultural program of former president Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s martial law. Today, synthetic fertilizers are a growing contributor to the vicious cycle of warming temperatures in the Philippines, according to a report by Climate Tracker Asia.

By 2050, nitrous oxide emissions are on track to increase to 24.4% in the country. Nitrous oxide is a type of greenhouse gas, mainly released through the use of synthetic fertilizers and poor agricultural waste management practices.

Synthetic fertilizer was widely and systematically introduced in Marcos Sr.’s Masagana 99, an agricultural program implemented on May 21, 1973, eight months after the late dictator declared martial law.

Marcos Sr., the incumbent president’s father and namesake, was scrambling to address the national rice shortage and synthetic fertilizers were part of the “technological package” to address the crisis. Masagana 99 promised to produce 99 cavans of rice per hectare, “even on non-irrigated land,” according to a report by researchers of the Third World Studies at the University of the Philippines – Diliman.

(Read ‘Success’ of Masagana 99 all in Imee’s head – UP researchers)

Ramos, 68, recalls a time before the Marcos Sr. administration pushed for farmers to plant high-yield rice varieties. Back then, he said he could have a successful harvest using rice grain varieties such as Wag-wag, Binato and Ramilad using only water.

“Meron [ding] hito, gurami, palaka, talangka, kuhol. Nasira lahat ‘yon dahil pinayagan ‘yung furadan at glyphosate,” said Ramos referring to pesticides and herbicides which have been at the center of controversies for their reported harmful effect on people, animals and the environment.

Furadan is banned in the United States, Canada, European Union and Sri Lanka. Glyphosate is banned in Vietnam and is on track to be banned in Mexico.

“Pinayagan sa Pilipinas yung mga [‘yon] kahit mga nakakasira sa kalusugan, kabuhayan at mga pananim,” lamented Ramos, who also chairs Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (KMP). “Winasak ang ating agrikultura, ‘yung natural.”

This is why Ramos calls for a rejection of proposals reviving Masagana 99 and the Mining Act of 1995, which is criticized for having enabled the encroachment into the ancestral domains of indigenous people.

Age-Old Farming Tradition

In their tribal communities in upland Mindanao, women farmers take charge of implementing the Suragad/Sulagad farming method. They prioritize the health of the soil, making sure to let the land rest by following a planting schedule of different crops based on the weather patterns they have known since childhood.

Women farmers follow a ritual. In a basket, they collect the seeds for a particular planting season and pray for guidance from Apo te Kelayag (for Erumanen ne Menuvu) or Sëbotën (for Teduray). They bless these seeds and the bolo to be used for preparing the land where they will plant root crops and legumes when many stars brighten the night sky.

Unpredictable weather caused by climate change, however, has made it harder for these women farmers to set their planting schedules.

“Nalito na rin kami kung kailan ‘yung panahon ng tag-ulan, kailan ‘yung panahon ng tag-init. Tapos hindi na namin alam kung kailan namin itatanim itong kamote, kailan namin itatanim itong mais,” Taupan pointed out.

Struggle Against Mining, Land Grabbing

Both Taupan and Cornelio noted that mining and other development activities near or within their ancestral land have been a huge block in continuing their traditional farming practices. Their ancestral domain and their farms are getting smaller and smaller because of mining projects and large agricultural plantations.

While before, Taupan said they could freely move from one place in their ancestral domain to farm in another area in order to allow the land to rest after a harvest. When they do this now and return to check the land they temporarily left behind, they discover that it had been blocked off for various projects and businesses.

“Malaya ipinapapasok itong mga iba’t ibang developments, sabi nila. Developments para sa kanila pero hindi naman angkop ito doon sa pamayanan ng katutubo kaya doon nagkakaproblema,” Cornelio said.

Mining is the “biggest driver of land conflicts” involving indigenous land. Around 223,000 hectares of new mining projects in ancestral domains were approved in 2023, according to a 2024 report by the Legal Rights and Natural Resources Center. This means that over 1.3 million hectares of various projects within or in proximity of ancestral domains have been recorded by 2023, according to the same report.

Uphold Ancestral Rights

If elected, Ramos promises to fight for the rights of indigenous people to their ancestral lands and their traditions.

“Titiyakin natin na ang lupa ng mga katutubo ay hindi winawasak, hindi sinisira,” he tells voters.

“Isa sa mga pinaglalaban ng KMP at ng Makabayan ay mga karapatang lupa ng mga katutubong mamamayan, ‘yung tinatawag na ancestral land o ancestral domain at respect sa kanilang pagpapasya sa sarili,” Ramos adds.

Taupan and Cornelio make the same call for candidates vying for a seat in both houses of Congress and ultimately shape the country’s agricultural policies as well as provide the budget for agricultural programs for the next three to six years.

“Una, i-award na talaga nila yung titulo ng AD (ancestral domains) kasi marami pa ang mga ancestral domain ang hindi pa naibigay ‘yung titulo. Dapat kilalanin, respetuhin talaga nila ang mga karapatan at ipatupad sa amin ‘yung karapatan namin sa lupang ninuno,” Taupan urged.

“Sa paniniwala namin, ang lupa ay buhay, pero paano pa madudugtungan ‘yung buhay namin kung pilit nilang inaagaw ‘yung lupa namin?,” she demanded.