The Philippine chairmanship of the golden anniversary of Asean adopted for its theme, “Partnering for Change, Engaging the World.” It also adopted six thematic priorities: 1) a people-oriented and people-centered Asean, 2) peace and stability in the region, 3) maritime security and cooperation, 4) inclusive, innovation led-growth, 5) Asean’s resiliency, and 6) Asean as a model of regionalism, a global player.

There is no tangible manifestation that the first big meeting of its chairmanship – the Asean summit in April has accomplished any of its priorities.

President Duterte, chairman of this year’s Asean meetings which coincide with the organization’s golden anniversary.

The only manifestation may include: the good behavior of the President; the rather extravagant display of traditional Filipino hospitality; and the efficient and effective security and protocolar arrangements by the Organizing Committee.

The “Chairman‘s Statement” is a disappointment, mainly because it is made in China. China was omnipresent in most meetings, the perception is China was the biggest winner in the summit. Congratulations to Chinese diplomacy.

There was even a unique acknowledgement of the improvement of bilateral relations between some Asean member states and China. No wonder China is happy with the “Chairman’s Statement.”

The Philippines failed to exercise its leadership as chair of the summit and missed a golden opportunity to contribute something significant to the organization’s golden anniversary. The chair is expected to set the tone and dominate the proceedings of the meetings. This is traditional and accepted practice and par for the course and followed in the past summits by strong chairmen. There is no such thing as a neutral chairman and to be coy and timid about his role.

The most pending issue of the day, China’s –aggressive action in the South China Sea, was not discussed simply because the Philippines as chair did not want it for fear of offending China. The other Asean member states found a convenient way to be silent – the silence of the lambs.

What happened to “Asean centrality?”

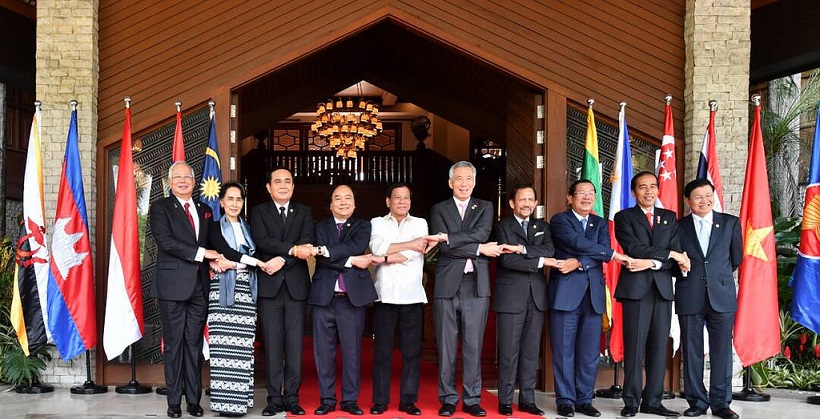

The traditional linking of arms of the leaders in the 30th Asean Summer Retreat

The post-summit assessment/response to the absence of any reference to the Arbitral Court decision for the Philippines draws attention to paragraphs 7 and 120 of the Chairman’s Statement.

Paragraph 7: We reaffirmed the shared commitment to maintaining and promoting peace, security and stability in the region, as well as to the peaceful resolution of disputes, including full respect for legal and diplomatic processes, without resorting to the threat or use of force, in accordance with the universally recognized principles of international law, including the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Paragraph 120. We reaffirmed the importance of maintaining peace, stability, security and freedom of navigation and over-flight in and above the South China Sea. We welcomed the operationalization of the Guidelines for Hotline Communications among Senior Officials of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs of ASEAN Member States and China in Response to Maritime Emergencies in the Implementation of the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea and look forward to the early operationalization of the other early harvest measure which is the Joint Statement on the Application of the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES) in the South China Sea. We took note of concerns expressed by some Leaders over recent developments in the area. We reaffirmed the importance of the need to enhance mutual trust and confidence, exercising self-restraint in the conduct of activities, and avoiding actions that may furthercomplicate the situation,and pursuing the peaceful resolution of disputes, without resorting to the threat or use of force.

This is reading too much of what is not there. In fact the statement from the Asean summit in Laos last year talked about land reclamation and militarization in the South China Sea. The Philippine summit took a step backward.

A great deal of focus is being given to a putative Code of Conduct in the South Chinas Sea a priority achievement of the Philippine chairmanship insofar as maritime security and cooperation is concerned.

They are looking to June for a draft framework and to end of the year for a Code. This is misplaced optimism.

The process is still at the technical working group level; there is no clear undertaking of what a framework agreement is. Does Asean itself have? Moreover, as President Widodo of Indonesia said, maritime security and cooperation must go beyond a code of conduct in the air.

The Philippine chairmanship of Asean 50 may still be unfolding. Let us hope that incoming meetings of Asean will take more care of our priorities and move the organization forward as a “model of regionalism, a global player.”

The author is a veteran Philippine diplomat. He was the Philippine Permanent Representative to the United Nations from May 2003 to February 2007. Prior to that, he was Foreign Affairs Undersecretary for Policy.