By YVETTE B. MORALES

ELEVEN years ago, Tina* was raped by two men on her way home from school in Rizal one night. As she struggled, nobody heard the 11-year-old deaf child. Seeking justice for more than a decade, she remains without a voice in her own trial in court.

During the presentation of her case, she was allowed volunteer interpreters to speak for her in court, but afterwards the court in Antipolo just stopped issuing a subpoena for an interpreter, leaving Tina in silence during hearings.

When she first heard about the case, former public special education teacher Liwanag Caldito of Support and Empower Abused Deaf Children, Inc. (SEADC) helped with the interpreting.

SEADC is a nongovernment organization working to raise awareness of human rights and personal safety among Deaf children in the community.

“Hindi naiintindihan ng bata kung anong pinagsasasabi nila (The child could not understand what they were saying). She doesn’t know whether she should say yes or no,” said Caldito, also a founding member of the Philippine National Association of Sign Language Interpreters.

When Caldito interpreted for Tina, the court asked her whether she was licensed or not. “They would like to have people who are qualified. For those who aid the Deaf, we just help without thinking of the licensing,” she pointed out.

According to a September 2004 memorandum by then chief justice Hilario Davide, the Office of the Court Administrator (OCA), upon the request of lower courts, is mandated to provide for sign language interpreters (SLIs) to “prevent possible miscarriage of justice.”

But Caldito said some courts are not aware of the circular. Moreover, they do not know where to find registered interpreters. Unless the family asks for help, the Deaf remains silent in court.

“If they have a victim or perpetrator who is probably Italian, they will get an interpreter who is Italian, right? Why don’t they do it to the deaf? That’s our big question,” she said. Sign language is also a language, Caldito explained, and a barrier is created when no interpreter is present to help, she added.

Are the courts remiss?

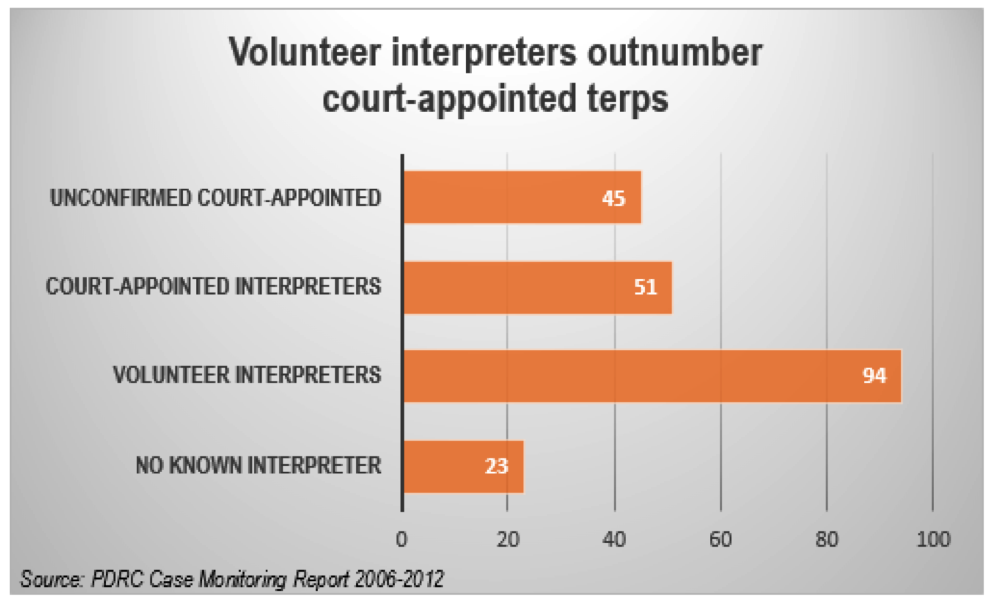

Based on the data from the Philippine Deaf Resource Center (PDRC), 11 percent or 23 of the 213 cases filed from 2006 to 2012 have no known interpreters.

Sometimes the parents themselves are oblivious to the needs of their Deaf child by failing to request the court for interpreters.

“If the parent were an educated parent, or if the parent understood what is needed, they possibly would [hire an interpreter]. We don’t hear from parents a lot,” Caldito said.

The 2004 memo also specified that savings from the budget of the lower courts be the source of payment of SLIs. The OCA later issued Circular No. 104-2007 prescribing the guidelines on the payment of the services of a hired SL interpreter.

The OCA shall pay the interpreter either on a per day or per appearance basis, with additional transportation allowance for cases to be heard outside the National Capital Judicial Region.

But in practice, SLIs do not get paid most of the time because they are stereotyped as volunteers or charity workers for the Deaf.

Based on the parallel report of the Philippine Coalition on the United Nations Convention on the Right of Persons with Disabilities which assessed the implementation of the Convention in the Philippines from 2008 to 2013, only two sign language interpreters have been compensated by the SC since 2004.

Even Tina’s volunteer interpreter was not compensated, Caldito said.

Tina has moved on with her life with a husband and child, but she still hopes for justice to be served.

For the Deaf advocate, justice has to be delivered swiftly, otherwise “there is no justice,” she said, adding that one of three Deaf is known to be abused.

Victims twice over

Caldito cited no official statistics to support her statement, but VERA Files in a 2012 report, said six rape cases were recorded in June alone. However, communication barriers between law enforcers and the Deaf victims have impeded justice. (See Deaf children prone to sexual abuse, says NGO)

“A lot of things that happen to them are not drawn into a court case,” Caldito said, citing other problems Deaf people encounter in the course of seeking justice.

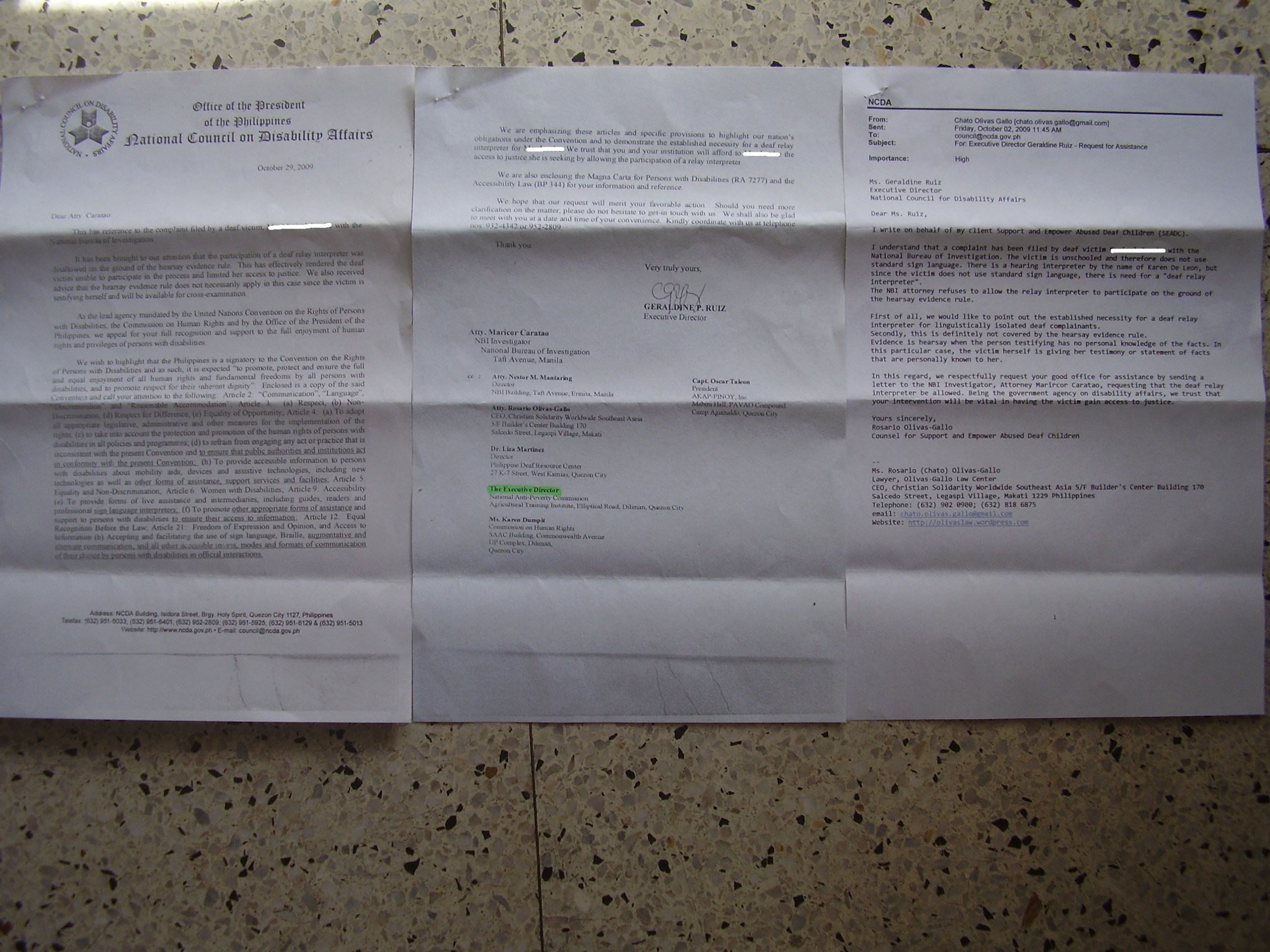

Six years ago, Caldito needed to write a letter to the National Council on Disability Affairs (NCDA) after the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) refused to accept the testimony of another Deaf child who was also raped through the deaf relay.

A deaf relay consists of an uneducated deaf, an educated deaf, and a hearing interpreter. It is usually used when the hearing interpreter cannot understand what the uneducated deaf is trying to say, she explained.

The NBI said the statement was only hearsay because it didn’t directly come from the Deaf, Caldito said. “[I asked them], ‘can you as the investigator understands what the victim is trying to say, without the relay, or without the interpreter?’ ”

In the letter written to the NCDA by lawyer Rosario Olivas-Gallo, counsel of SEADC, she said the case is not covered by the hearsay evidence rule.

“Evidence is hearsay when the person testifying has no personal knowledge of the facts. In this particular case, the victim herself is giving her testimony or statement of facts that are personally known to her,” Gallo wrote.

For her part, then NCDA executive director Geraldine Ruiz highlighted provisions of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, of which the Philippines is a signatory, in her letter to the NBI.

Article 9 of the Convention says that State Parties should “provide forms of live assistance and intermediaries, including guides, readers and professional sign language interpreters” and “promote other appropriate forms of assistance and support to persons with disabilities to ensure their access to information.”

“You have to trust the interpreters being able to say exactly what the deaf is trying to say. Otherwise, [it’s] useless. But we will not go without having to interpret for them,” Ruiz added.

Eventually, the NBI accepted the statement, Caldito said.

The PDRC noted that 75 percent of the 63 cases involving unschooled deaf parties do not have an appointed deaf relay interpreter.

The SEADC, on the other hand, managed to get 20-year-old Geoffrey* out of jail in 2007.

He was accused of fondling a girl he was asked to bathe. “It was possible somebody else did it and blamed the Deaf. [They] think by blaming the deaf, he wouldn’t be able to complain because nobody would listen to him,” Caldito said.

Apart from the SEADC, the other non-government organization that caters to the sector is the Filipino Deaf Women’s Health and Crisis Center.

Not enough trained interpreters

There are nearly a hundred enlisted professional interpreters in the Philippines. But for Filipino Sign Language interpreter Catherine Joy Villareal, their numbers are not enough to cater to the needs of the Deaf community, particularly because of the lack of formal and sufficient training.

“Although there is a need for interpreters, you really have to be fluent. It will take years before you can consider making a career out of it,” she said.

John Baliza, head of the Philippine National Association of Sign Language Interpreters, agrees. “I would always emphasize that learning sign language is very different from learning how to interpret. It requires years of experience and training to be able to effectively interpret for the deaf,” Baliza said.

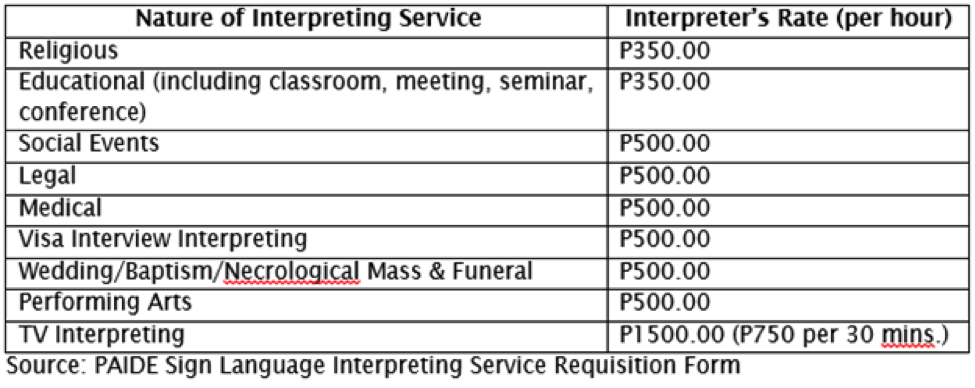

Despite these investments, SLIs are sometimes not properly compensated, and their rates not fixed.

SLIs are commonly hired to interpret in court proceedings or in television insets. However, there are also times when they are being recruited to sign in social events like weddings and funeral services.

The Philippine Association of Interpreters for Deaf Empowerment (PAIDE), for instance, charges P350 to P1,500 per hour depending on the nature of interpreting service.

Standard practice allows interpreters to take a rest after every 20 minutes of continuous signing, even in the absence of an alternate. Ideally, the contractor should provide at least two interpreters to ensure high quality of interpreting for occasions that would last for more than an hour.

In some cases, however, and perhaps because of budget constraints, only one interpreter is being hired to sign for hours without any rest period which also has a corresponding effect on the quality of the interpretation.

Villareal also said they lack the health insurance needed “for such a risky job.”

For instance, SLIs who have been recruited as court interpreters are also at risk whenever they handle cases of abuse and trafficking among children and adults who are deaf.

Interpreters become the target of death threats from the abusers’ families and syndicates, yet they do not receive any security assistance from the court or police and would end up either protecting themselves or withdrawing from the case.

“I just wish that the time will also come when Filipino Interpreters, whose lives are put at risk by taking sensitive cases in courts and anywhere else, would also demand for their rights – safety, proper compensation, health benefits, etc. – while in the process of completing their interpreting duties,” Villareal said. (With Verlie Q. Retulin and John Paul Ecarma Maunes)

*Not their real names.

(Yvette B. Morales and Verlie Q. Retulin are University of the Philippines students writing for VERA Files as part of their internship.)