By MARIA FEONA IMPERIAL

IN the Philippines, one spoken word can have several variations in meaning. The Tagalog word for “bird”, for instance, is the same as the Kapampangan for “egg.” Indeed, one must be very careful in telling the classic story of which came first.

There are 182 living languages used across the archipelago, which change from one town to another. Though some words such as “sun,” “rain,” “rice” and most counting numbers share common roots, each language maintains a distinct key feature in terms of syntax, accent, grammar, among others.

Hence, when people from the north and south of the country meet for the first time, communication becomes possible – with difficulty sometimes – through Filipino, the national spoken language,

But for the Deaf community, there is no universal sign language to bind its members together. Interestingly, even if they sign differently from each other, the Deaf can converse through pictures rather than words.

It would not be surprising at all that “deaf Japanese and deaf Filipinos understand each other more easily than their hearing counterparts do,” said Dr. Marie Therese Angeline Bustos, sign language interpreter and special education professor at the University of the Philippines in Diliman.

Contrary to what most people know, there are in fact two major categories of sign language used in the Philippines.

The first is “Sign Language” such as the Filipino Sign Language (FSL) or the American Sign Language (ASL), which is “naturally emanating from the Deaf,” Bustos said. The other one is “Artificial Signing System (ASS),” which follows certain grammar rules.

“The FSL has nothing to do with spoken Filipino. It basically refers to sign language used by the Deaf community in the Philippines,” Bustos said.

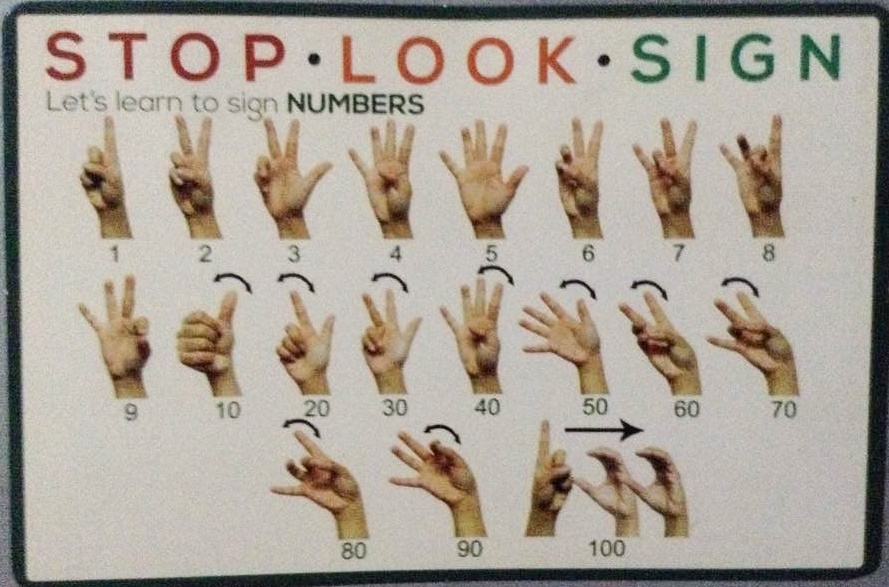

How to do sign language in the Philippines from the Philippine Deaf Resource Center (PDRC)

According to the Department of Education (DepEd) K to 12 curriculum guide for mother tongue, sign languages, such as FSL, are visual-spatial while spoken languages, such as spoken Filipino, are auditory-vocal languages.

In sign language, information is conveyed through the shape, placement, movement and orientation of the hands as well as movement of the face and the body. Meanwhile, linguistic information is received through the eyes, the guide said.

“It is visual in a sense that it is non-spoken,” Bustos said. “So, even if there is variation in an archipelago, sign language is easily understood because it is highly visual,” she added.

For instance, while there may be variations in demonstrating a “tricycle” through sign language in Visayas and Manila, it will most likely be signed in a similar way.

According to the DepEd guide, FSL is rule-governed, having its own linguistic structure – phonology, morphology, syntax, and discourse.

It is highly influenced by the ASL, which was brought to the Philippines in the 1900s by the American teachers who were instrumental in establishing the Philippine School for the Deaf (PSD), Bustos said.

“Like FSL, ASL is simply a sign language used in [North America] and is not to be confused with English,” Bustos said.

In 1974, the resurgence of the Peace Corps brought American volunteers that settled in Visayas, which may explain why most of ASL users in the Philippines are in Region VI, she said.

Meanwhile, most ASL users also belong to the older age brackets because of direct language contact with the Americans, said Liwanag Caldito, one of the founding members of the Philippine National Association of Sign Language Interpreters (PNASLI).

ASL, however, is not equivalent to FSL due to varying hand orientations and facial expressions.

Caldito said in fact while ASL and FSL both make use of the alphabet, the letter “T” is signed differently due to cultural differences.

In addition, Filipinos sign in a more animated and expressive way compared to Americans, especially when using interjections that denote feelings of surprise, she said.

For this reason, FSL, she said, is more a “picturesque” kind of sign language. “It is able to capture the idiosyncrasies like how Filipinos would talk.”

“When asking questions, for example, typically, the indicator would be raising one of his or her eyebrows or wrinkle his forehead. These facial expressions indicate questions such as what, when and why,” Bustos said.

There are also regional languages that reflect cultural differences and the geographic situation of the Philippines, Caldito said.

However, she estimates that 70 percent of the Filipino Deaf community, mostly from urban areas, uses FSL.

“It depends on how far they are from the center of civilization,” she said.

Moves to make FSL the national sign language in the Philippines only came much later. “We’re not a strong personality to insist on having a local sign language,” Caldito said.

Meanwhile, ASS, the second major category of sign language used in the Philippines highly depends on the alphabet and proper syntax. Signing in Exact English (SEE), which is still used in some schools for the Deaf such as the Miriam College, is an example.

SEE, which can be referred to as simultaneous signing or simply, sign and speak, depends largely on the use of hands.

In contrast to Sign Language, which makes use of non-manual signals such as raising of the eyebrows, tilting of the head or closing of the lips, the ASS has core language signs following the word order, according to Bustos.

“In SEE, every word has a corresponding sign,” Caldito said.

For instance, when signing “how are you” in SEE, every word must be expressed compared in Sign Language, where it can be easily interpreted as “how you.”

The problem with SEE arises when there are too many signs, so at the end of the whole sentence, there are words that tend to be missed or left out, Caldito said.

Sign Language and ASS are both standardized forms of sign language, which are familiar mostly to the Deaf who have attended formal schooling.

“Typically, when you have deaf parents, a typical deaf child will not sign similarly to other children. The child attends school for standardization,” Bustos said.

Deaf people who were unable to attend school sign in a highly gestural manner, according to Bustos. Unfortunately, because of their situation, these people are typically the victims of abuse, she said.

But there must be a way of getting their messages across, Bustos argued, and this should be the responsibility of the sign language interpreter.

She said interpreters have to interpret depending on their audience. Speaking in front of jeepney drivers would need a different level of language compared to appearing before senators in Congress.

“When we have to go to court, there must be deaf-relay interpreters, or people who are deaf who are familiar with both standardized and gestural [sign language],” she said.

The deaf-relay interpreter then relays to a hearing interpreter what the victim has said in a standardized form.

FSL, as with all other sign languages in the world, does not have a written form. People who are deaf do not read and write in sign language, rather they become literate in a second language, according to the K to 12 guide.

This is why broken grammar is common to the Deaf when expressing themselves in written form.

“The deaf person writes the word following the grammar of SL, but SL has no written form of spoken language,” Bustos said. “For instance, in Sign Language, ‘I am Therese’ becomes ‘Therese Me’.

For Bustos, Sign Language is highly “three-dimensional.”

However, the command of the language still depends on personal background and circumstances.

“Normally, smarter deaf kids would have a better command of the language, depending of course on the resources, tutors, and parents who take time,” she said.

While the diversity of sign language used in the Philippines enables every person who is deaf to communicate and engage in discussion regardless of the kind he subscribes to, Bustos said it is very important to have a national sign language to facilitate education and negotiate regional variations.

(The author is a University of the Philippines student writing for VERA Files as part of her internship.)