By VJ BACUNGAN and DANICA UY

A BEVY of red tricycles hurtle down Bonifacio Avenue, a four-lane national highway cutting through Cainta town in Rizal, their buzzy two-stroke engines leaving plumes of blue smoke in their wake. They overtake another tricycle which, even from afar, stands out from the rest.

At six feet tall, this tricycle towers over all its three-wheeled counterparts on the road. What is more odd is that its sidecar isn’t ferrying people but an empty wheelchair.

The driver turns right and drives up to the Cainta Municipal Government complex. He pulls over under a tree at a small parking lot. He then seats himself onto the wheelchair and rolls off the ramp that forms the back of the sidecar.

The driver is Juanito Mingarine, a multi-awarded athlete who lost the use of his feet after contracting the polio virus at eight months old. He is soon joined by Elfren Fernandez, an electrical engineer who uses crutches, having been born without a right leg and with a disfigured right hand; and Joseph Asoque, a draftsman who uses a prosthetic left leg.

Meet three of the five brains behind the adapted tricycle that they see as one of the answers to wheelchair users’ need for mobility—and for speed.

The other two are Alvin Lagonoy, a freelance building contractor who also runs a computer business, and Violeta Sapalit, who teaches technology courses over the Internet. Like Mingarine, Lagonoy and Sapalit had polio as children, which impaired their ability to walk. They, too, use wheelchairs.

From laundry soap to adapted tricycles

With P75,000 in initial capital, the five started up JAJEV Industry—the name is an amalgam of the first letter of their first names—in 2013. The company has gone beyond producing laundry detergents to providing mobility options for persons with disabilities (PWD), ranging from solar-charged wheelchairs to full vehicular conversions.

“We cater to PWDs who miss driving and even first-time PWD drivers,” said Mingarine, showcasing his adapted tricycle.

(Read English subtitles of video)

The vehicle consists of a 125cc underbone Honda motorcycle and a special sidecar that allows him to ride his wheelchair on and off it.

Another unique feature is a handle welded to the pedals of the semiautomatic transmission, allowing him to change gear with his left hand.

Mingarine said a sidecar conversion like his costs from P10,000 to P11,000, excluding the cost of the motorcycle.

But conversion prices may vary since the company custom-designs each vehicle to suit the driver’s disability.

For riders who don’t need a sidecar to accommodate a wheelchair, but have trouble balancing on a standard motorcycle, Mingarine said JAJEV Industry can also provide a solution.

“We turn a standard motorcycle into a three-wheeler,” he said. “This costs a bit more, from P16,000 to P20,000 (excluding the motorcycle), since we have to alter the rear axle to handle two wheels.”

For those who prefer driving ‘stick’

Fernandez said JAJEV Industry can also modify cars for anywhere from P5,000 to P30,000 and that customers can choose from a range of adapted hand and foot controls.

“We don’t paralyze the original functions of the car,” he said. “The devices can be removed, so that regular people could drive it, too.”

Unlike many conversion kits that work only with automatic-transmission vehicles, Fernandez said the company can also adapt manual-transmission vehicles for around P50,000.

“An electro-pneumatic device is attached to the clutch pedal, in which sensors detect how much input there is on the accelerator. The vehicle effectively has an automated clutch,” he said.

Fernandez said if the driver lifts off the gas pedal to change gear or to brake, the device pushes the clutch pedal down automatically. Once the driver presses the gas pedal again, the device pulls it back up.

Foreign influences

Mingarine said their devices were inspired by designs from abroad, where PWD drivers are more common.

In fact, the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the agency in charge of enforcing federal vehicle safety laws, has guidelines for PWD vehicle conversions and driver testing. And although the European Union doesn’t have overall guidelines, member states are taking the initiative to provide mobility for PWDs.

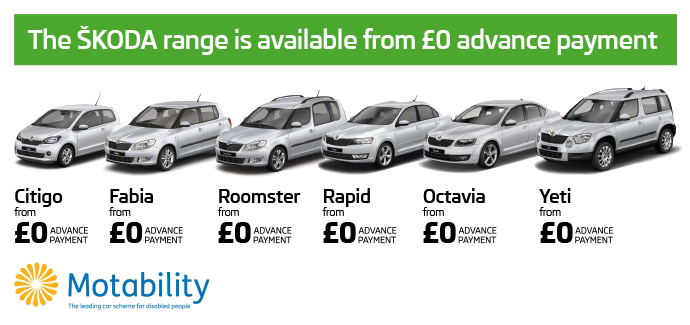

One such program is the U.K. Motability program. Here, a PWD may choose to use his or her government subsidy to lease a new car, scooter or powered wheelchair. The scheme also provides detailed guidelines for conversions and driver testing. A notable aspect is that car manufacturers are partners in the program, providing incentives for PWD drivers.

One such program is the U.K. Motability program. Here, a PWD may choose to use his or her government subsidy to lease a new car, scooter or powered wheelchair. The scheme also provides detailed guidelines for conversions and driver testing. A notable aspect is that car manufacturers are partners in the program, providing incentives for PWD drivers.

Mingarine said no such scheme exists in the Philippines, although JAJEV Industry would be glad to tie up with local car manufacturers to develop and manufacture adapted vehicles on a larger scale.

He also said JAJEV Industry follows its own design and safety standards because the government has not issued any guidelines for adapted vehicles.

This issue doesn’t surprise Robby Consunji, legal columnist for popular motoring magazine Top Gear Philippines, who said PWD drivers are not a priority for the Land Transportation Office (LTO).

“It’s kanya, kanya (each to his or her own). PWDs really must resort to self-invention to drive a vehicle and likewise have to justify their designs to the LTO,” he said.

LTO ‘not competent’ for the job

Consunji said the problem stems from vague standards and poor implementation of the law, compounded by the fact that the LTO does not have the expertise or the equipment to properly evaluate the drivers and the vehicles.

Section 26 of Republic Act 7277 or the 1992 Magna Carta for Persons with Disabilities grants PWDs the privilege of driving motor vehicles, subject to LTO regulations. Two years later, the agency issued Memorandum Circular 94-188 to comply with the enabling law.

The circular only allows the following PWDs to obtain nonprofessional driver’s licenses: (1) an orthopedically impaired person with an amputated left or right leg or amputated left or right arm, (2) persons who had polio with one paralyzed leg, (3) persons with visual impairment in either the left or right eye, and (4) persons with speech and hearing impairment who must use hearing aids. It doesn’t allow blind people, deaf people and double amputees to drive.

“It’s really subjective, though. There is no clear pass or fail. It’s a matter of wooing the doctor and the LTO examiner to let you drive,” said Consunji.

Guidelines in the works

Louie Miranda, a dentist at the LTO Central Office on East Avenue who serves as chairman of the LTO Accredited Physicians and is a member of the Department of Transportation and Communications Task Force on Accessibility, concedes that there are no set standards yet for PWD drivers and vehicular conversions.

He said the standards are still being formulated.

“Right now, it’s on a case-to-case basis,” Miranda said. “When a PWD registers his or her adapted vehicle, the motor vehicle inspector checks to see if it is a viable and safe design.”

However, he said the LTO issued a circular in 2013 to address the concerns of PWD drivers who want to get driver’s licenses.

Memorandum Circular VPT-2013-1803 reiterates earlier LTO circulars that require, among others, PWDs applying for or renewing their licenses to get their medical certificates from specialized physicians.

Mingarine said that although JAJEV Industry prioritizes ease of use and total customization, it is willing to comply with stricter government safety standards should these be issued.

Big demand, big money

In light of all these, one big question remains: Just how big is the demand for adapted vehicles?

“There’s actually a lot of money to be made here,” Fernandez said.

According to data from AMPI-Mega, the private company that prints driver’s license cards for the LTO, the LTO issued nearly 193,000 driver’s licenses to PWDs in 2008.

Around 95 percent were for license Condition A or drivers who must wear eyeglasses while driving. The remaining 5 percent (around 9,500 licenses) were issued to drivers with more serious impairments.

Of the latter group, nearly two in three were for Condition D drivers, who have visual impairments and are only allowed to drive from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. Nearly a quarter were for Condition C drivers, who require special equipment for their lower limbs.

Eight percent of the licenses, on the other hand, were issued to Condition B drivers, who require special equipment for their upper limbs, while the remaining 4 percent were obtained by Condition E drivers, who have hearing impairments and must use hearing aids.

Driving means freedom for PWDs

Bing Baquir, head of the National Council for Disability Affairs’ subcommittee on Accessibility and Transportation, said driving is more than just a convenient way of getting around for PWDs.

Bing Baquir, head of the National Council for Disability Affairs’ subcommittee on Accessibility and Transportation, said driving is more than just a convenient way of getting around for PWDs.

“For persons with disabilities, it’s a priority for them to drive because it means independent living. They want to be self-reliant,” she said.

Fernandez said personal mobility is certainly important to PWDs, especially since public transportation is still not a viable option for them to get around.

He said JAJEV Industry has done 15 conversions so far and is looking to expand production. However, he said it is in dire need of more investors and equipment.

“We have been using our friends’ machine shops just to make the parts. The proof of concept is already here. We just need help from willing partners,” he said.

But aside from helping PWDs become more mobile, Fernandez said the ultimate goal of JAJEV Industry is to create sustainable employment for PWDs.

“It’s hard for a PWD to find work in this country,” he said. “Our vision is to create a business that would help PWDs have employment with a high-paying salary.”

For inquiries on JAJEV Industry’s products, contact Elfren Fernandez at 0919-9938988, 0915-1868050 or elfren143@yahoo.com.ph

(The authors are journalism majors of the University of the Philippines-Diliman. They submitted this story for the journalism seminar class “Reporting on Persons with Disabilities” under VERA Files trustee Yvonne T. Chua.)