By ANDREW JONATHAN BAGAOISAN and MARK ANGELO CHING

OFFICIALS of the Commission on Higher Education are used to dealing with members of congressmen making all sorts of demands—from requests for scholarships to following up the permits of nursing schools.

But the buck of political pressure does not stop in Congress. It goes all the way up.

A former commissioner recalled being contacted by a Malacañang official to order CHED to relax its requirements, specifically the one requiring nursing schools to have a partner tertiary base hospital.

The former CHED official also pointed to a school owner, a close supporter of President Gloria Arroyo, applying to open other nursing campuses. The school, which did not meet the hospital requirement, was among 23 that were ordered closed by CHED in 2005. CHED then received an order from Malacanang to give that particular school a permit.

Three years after, the school’s owner figured among the President’s choices for CHED chair. Arroyo eventually picked Dr. Emmanuel Angeles of Angeles University, who was not involved in that controversy, to be chair.

Presidential support lacking

Describing the relationship between the Palace and CHED, the former official said, “If the President supported us more, CHED would have been stronger.”

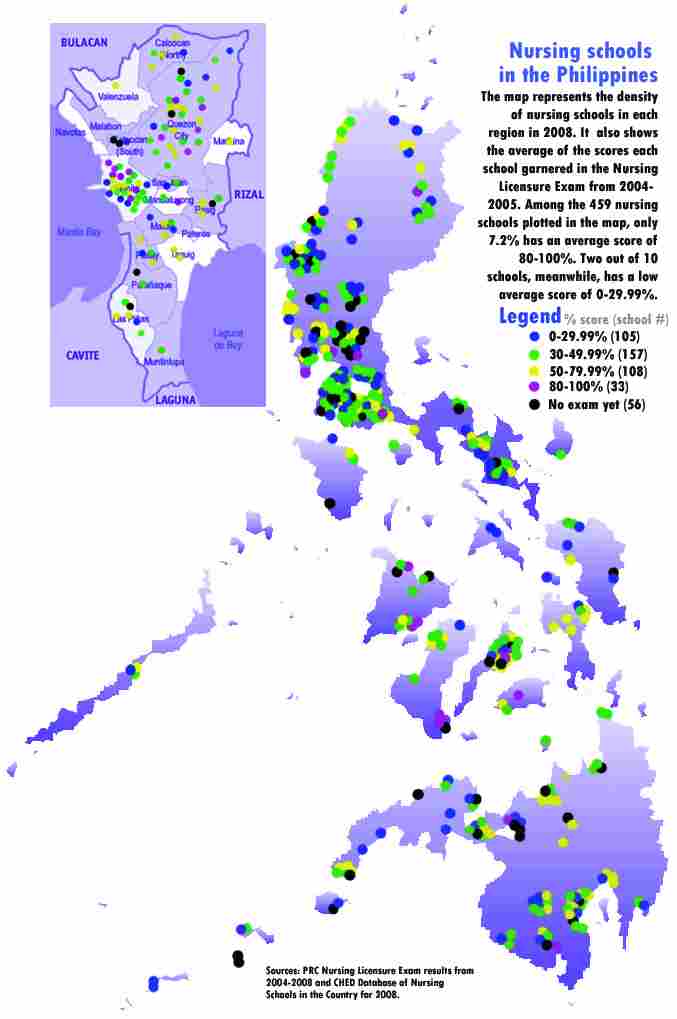

As it was, the number of nursing schools in 2007 increased by 230 percent from 2001. Most of these perform very poorly in the Nursing Licensure Exams (NLE). In fact, one out of every two nursing schools whose graduates took the board exam last November scored only 50 percent or less.

As it was, the number of nursing schools in 2007 increased by 230 percent from 2001. Most of these perform very poorly in the Nursing Licensure Exams (NLE). In fact, one out of every two nursing schools whose graduates took the board exam last November scored only 50 percent or less.

Data also show that from 2001 to November 2007, a dozen schools have scored zero to 3 percent in at least three exams. Four of these have already closed down due to the low number of enrollees or other market forces. Eight, however, are still operating.

The dire state of nursing education is quickly blamed on CHED which, under its Memorandum Order No. 30 issued in 2001, could have closed down substandard educational institutions such as those eight schools that scored low percentage points. It could have also phased out the nursing programs of about six schools that garnered only four to 10 percentage points in three exams in the last five years.

Former CHED chair Carlito Puno said, however, that owners of the nursing schools do not follow the commission’s orders. For instance, a commission decision in 2005 raising the required passing rate from 10 to 30 percent and phasing out underperforming nursing schools triggered a war between the regulatory body and the school owners.

Had the 30 percent passing rate been applied to the exam performances from 2004 to 2008, CHED could have closed down two out of every 10 nursing schools nationwide by simply computing their average scores.

But Puno said, “My God, they really fought us. They brought us to court.”

Court case vs CHED

The school owners, for instance, filed a case against CHED in the regional trial court in Pangasinan, where their leader, lawyer Gonzalo T. Duque, president of Lyceum Northwestern–Florencia T. Duque College in Pangasinan, was based. The owners succeeded in getting the Dagupan trial court to issue an injunction and a temporary restraining order in June 2005 preventing CHED from closing them down. Owners of nursing schools elsewhere in the country then began invoking the TRO to prevent their closure.

An assessment of the performance of the nursing schools from 2004 to 2008, published by the Professional Regulation Commission as required by the PRC Modernization Act of 2000, showed six schools whose nursing programs should be phased out based on NLE scores. These schools are located in Metro Manila, Regions 1 and 8, Soccsksargen and the Cordillera Administrative Region.

The PRC data also showed eight other schools in various parts of the country whose nursing programs should be closed down. One is in Metro Manila, while the others are in Regions 2, 3, 5, 9, 10 and the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao.

The case of the two nursing schools in ARMM is a totally different matter altogether. These two schools are the worst performing in every board exam. But William Malitao of the CHED Office of Programs and Standards (OPS) said, “They have an autonomous CHED there. It is in charge of the regulation of these two schools. We can’t do anything about them.”

These two ARMM schools are also owned by powerful families in the region with ties to the ruling party Lakas-CMD.

As for the other underperforming nursing schools, Malitao said they still invoke the TRO to this day. This is why CHED still has not closed down any nursing school based on performance rates.

Puno learned from a retired Supreme Court justice in 2006 that the TRO applies only to Pangasinan. The law also sets an expiry date for TROs. But CHED has been treading gingerly on this matter.

The school that spearheaded the move for the TRO, Lyceum Northwestern–Florencia T. Duque College, was founded in 1969 by Dr. Francisco Q. Duque Jr. and his wife, Florencia. Duque was the health secretary during the term of the late President Diosdado Macapagal.

Duque’s son, Francisco III, is now President Arroyo’s health secretary. He was the executive vice president of the Lyceum Northwestern–Florencia T. Duque College from 1991 to 2000. Documents from the Securities and Exchange Commission show that Duque and seven of his relatives each held around 12 percent of the college’s stocks as of 2003.

To get around the TRO, the commission decided in an en banc resolution in 2007 to phase out the nursing schools on the basis of other deficiencies, such as lack of a base hospital and qualified faculty members rather than poor performance in the board exams. But even on those bases, Malitao admitted that CHED has not yet phased out any nursing school.

“We have no budget to tour and make an inspection of the schools,” he said. “The appropriation for CHED only goes to its internal operations. There is not enough money for regulation.”

CHED’s 2007 financial statement showed that less than 40 percent of its P1.6-billion budget went to maintenance and other operating expenses. No particular amount was allotted for the inspection of schools.

Effect of global crisis

The mushrooming of substandard nursing schools in the country flies in the face of the global economic crisis that has narrowed down prospects for nurses seeking employment in the so-called traditional nursing markets, most especially the United States. New markets for nurses, however, are opening in countries like New Zealand, Norway and Japan.

The problem is not that the demand for Filipino nurses has gone down, but that the continuing local and foreign demand is not enough to employ the oversupply of nurses, said Philippine Nurses Association (PNA) president Teresita Barcelo.

According to the PNA, about 100,000 nurses are currently jobless. That number does not count the 39,000 new nurses who passed the November 2008 nursing licensure exams and the thousands of others who graduated this summer.

Moves to address the crisis in nursing have so far focused on providing jobs for the graduates. The Arroyo administration launched in February the Nurses Assigned to Rural Services or NARS program, a P500-million year-long program that is part of the government’s Economic Resiliency Plan to deal with the financial crisis.

The program aimed to send 10,000 nurses to public hospitals and health centers in the country’s poorest areas. The nurses would be paid monthly stipends of P8,000. In addition, they would acquire the work experience that overseas employers require.

More than 11,000 nurses applied for the 5,000 slots of the program’s first six-month cycle that began in April. But while the administration is attempting to address the lack of jobs with an emergency employment program, this has room for just 10 percent of the jobless. Members of the nursing community interviewed for this report pointed out that the government should address the root of the problem.

Government, they said, should impose stricter measures on nursing education, a job that is supposed to be done by CHED. The board exams last November, for instance, saw the biggest number of examinees so far at 88,000. Only less than half, or 44.5 percent, passed.

Josefina Tuazon, dean of the University of the Philippines College of Nursing, said the present crisis might actually present a strong reason for CHED to resist political pressure that is preventing it from cracking down on substandard nursing schools.

“How do you justify opening new schools when there is unemployment?” she said.

Former and present CHED officials, however, suggested that the problem and the solution might be structural in nature.

Administratively under Malacañang, CHED’s chair and commissioners are all appointed by the President. Getting its funds from Congress, CHED officials think they cannot afford to displease the lawmakers who have the power to approve—or cut down—its budget.

CHED officials also say the commission needs a bigger budget. Malitao said a bigger subsidy would help the commission monitor the performance of operating schools. Congress should also amend Republic Act No. 7722, or the Higher Education Act, which serves as the CHED Charter to give the commission more teeth in monitoring and closing down underperforming schools, he said.

But for Tuazon of UP and Barcelo of PNA, it’s not just money that CHED needs. The commission, they said, needs the political will to implement its own rules.

“Just because of the fear of litigation, you cannot implement a guideline?” Tuazon said, referring to the court cases filed by owners of nursing schools.

New guidelines

Last May, CHED reviewed and issued a new set of guidelines for nursing schools in time for the new schoolyear. Under 2009 CHED Memorandum No. 14, schools must comply with all requirements within three years after getting their permits.

The new memo also added detailed qualifications for deans and nursing instructors, and required base and affiliated hospitals. However, the new curriculum was reduced by 10 units and the hours required for hospital experience by 154.

Sanctions were expanded from one paragraph in 2001 to seven. Nursing schools are now required to keep their average board exam passing rate at 30 percent for the next three years or else be phased out. But the phase-out starts in 2013 and covers first-time takers only.

With decreasing demand overseas for nurses, the consequent decrease in nursing schools just might help improve the quality of nursing education.

Hopefully, Borromeo said, people would stop regarding nursing as merely a lucrative profession. “Those who have less-than-ideal reasons for opening a nursing school will probably get discouraged, which is good,” she said.

After all, Barcelo said, nursing schools should be teaching their students “the right values” rather than just preparing them for jobs abroad. Such students should be taught “what it means to be a nurse.”

She rued that many nursing students today do not even have their hearts in the profession because they were simply forced by their parents to take the course in order to help their families financially.

The current state of nursing schools and the prevalence of such an attitude among the country’s future nurses combine to make a distressing picture.

And that, Barcelo said, “is the sad story.”

(The authors are journalism graduates of the University of the Philippines. This two-part report is an abridged version of their thesis, which was done under the supervision of UP journalism professor and VERA Files trustee Yvonne Chua.)