By ALLAN YVES BRIONES, BRYAN EZRA GONZALES and MA. LUISA PINEDA

A FEW weeks before classes opened, the noise of hammers and saws resonated throughout the two-story Values Education Building of the Pedro E. Diaz High School (PEDHS) in Muntinlupa. Outside the building lay strewn desktops, plywood and filers teeming with documents of all sorts.

But the hustle and bustle was not part of the annual Brigada Eskwela or other preparations for school opening.

The school’s Values Education Building, prized for its fully equipped Special Education facilities for students with hearing disabilities, will be demolished, the first of five structures on campus found sitting on top of the West Valley Fault (WVF), a 100-kilometer that traverses 18 cities and towns in Metro Manila and adjoining provinces such as Bulacan.

The PEDHS has been taking this and other steps since it was identified as one of five public schools in Metro Manila transected by the fault, which could unleash the “Big One” or a 7.2 magnitude earthquake if it moved. The West Valley Fault is literally sleeping just beneath these schools.

Should the Big One come, structures directly above the fault like those at PEDHS would not survive due to ruptures that would be generated by the quake, Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology Director Renato Solidum.

“It can propagate into the surface,” he added. “So when there’s a building directly on top of it and the movement (of the ground) is horizontal, the ground will break.”

Buildings located within the so-called buffer zones or areas at least 50 kilometers away from the fault are not as safe as some would think.

“The effect of an earthquake is not confined to where the fault is, since the shaking is caused by the passage of the earthquake wave, then even 50 to100 kilometers away, it can be felt and the damage could be seen,” Solidum said.

A 2004 study conducted by the Japan International Cooperation Agency, Metropolitan Manila Development Authority and Phivolcs said the Big One will cause P2.3 trillion worth damages to the country’s business capital and seat of government, leaving around 33,500 dead and at least 100,000 injured.

Metro Manila Shake Drill

This Wednesday, the PEDHS is joining the Shake Drill organized by the MMDA to remind Metro Manilans that preparing for disasters could help minimize deaths, injuries and other losses.

But the school is no stranger to earthquake drills. Almost weekly, a school official would strike a huge bronze bell located at the covered court to launch the drill. He would bang the bell 10 times to call the students to vacate their classrooms and assemble at the school’s open ground, which has been designated as its temporary evacuation site.

The PEDHS has chosen against using the school bell because most of the time, students mistake the ringing of the school bell as recess time.

“Once the students hear the (bronze) bell, they know there’s going to be an earthquake drill,” Rogelio Cabanting Jr., the school’s Disaster Risk and Reduction Management (DRRM) coordinator, said.

Displaced students

The PEDHS is not the only public school in Muntinlupa that faces the worst-case scenario if the Big One hits. So are the Buli Elementary School and the Alabang Elementary School.

(The other two schools transected by the West Valley Fault are in Marikina.The Barangka Elementary School and the Barangay National High School have smaller student populations than the Muntinlupa schools.)

The Alabang Elementary School (AES) located two kilometers from the PEDHS tore down its Rodriguez building two years ago after administrators found that the West Valley Fault also transected the structure.

The PEDHS and AES have experienced a drastic drop in enrolment since Phivolcs issued the initial list of schools transected by the West Valley Fault and recommended several schools in Metro Manila to abandon some of their buildings. Students who have opted to stick it out have been or will be displaced by the demolition of their classrooms.

Enrolment at PEDHS has fallen from 7,248 in 2011 to 4,770 this schoolyear. AES’ student population has shrunk from 6,663 to under 5,500 for the same period.

Cabanting said more than a thousand of their students will lose their classrooms when the schools tear down the five structures. The Values Education building alone accommodated 420 students.

Students displaced by these demolitions will be spending the next few months in 12 makeshift classrooms to be installed at the school’s covered court.

Given the need to prioritize these students, the school is not offering senior high school for this academic term.

The school plans to add classrooms at the Social Sciences and Filipino buildings to address the shortage of classrooms and the lack of buildable space, Cabanting said.

Half of the four-story Technical Vocational Education building that lies atop the fault will be demolished, but the remaining portion will be extended toward an empty lot on the eastern end of the structure, he said.

At AES, the demolition of the Rodriguez building displaced more than 500 Grade 1 and 2 students. Makeshift classrooms were installed at the Cariño building.

Janet Linquico, the school’s DRRM coordinator, said these displacements convinced the administration to demolish the oldest structure in the campus, the Department of Education, Culture and the Arts (DECS) building, to pave the way for a new four-story schoolhouse. The school will also expand the Cariño building and connect the structure to the nearby Bunyi building.

“You can no longer build on top of these structures, so we have to demolish them,” Linquico said.

Schoolbuilding design

Engineer Isabelo Baleros of the Las Pinas-Muntinlupa District Engineering Office said the two public schools are partly to blame, having failed to meet the stringent building requirements for schools located on top of the fault, especially provisions for earthquake resilience.

As a result, the engineering office recommended that the affected buildings be abandoned.

Baleros said the two schools could still be retrofitted and reinforced with stronger materials in order to increase their resilience to earthquakes, except that the Department of Education is more focused on building new schools than fixing old ones.

“Most of our funds in Metro Manila are for four-story buildings in order to save space,” Baleros said.

The Department of Public Works and Highways has released a new standard design for schools: the DPWH Standard Four-Story School Building (12, 16 and 20 Classrooms). The guidebook contains a provision on soil-bearing pressures, which entails conducting soil tests on lands adjacent to the fault for signs of liquefaction.

DRRM programs

Despite these risks, however, both schools have no plans of closing their doors. Instead, the two schools have turned to developing and boosting their respective disaster risk reduction and management programs, making the most of what they have in ensuring the preparedness of their students, teachers and nonteaching staff.

The PEDHS, considered as having one of the most developed DRRM programs for any public school in Muntinlupa, conducts around four earthquake drills a month, Cabanting said.

To differentiate earthquake simulation exercises from fire drills, he said the school uses a separate siren located at the administration office to indicate a fire drill instead of the bronze bell.

Aside from these drills, the school has created DRRM committees for students, teachers and nonteaching staff who undergo rigorous trainings in first aid, basic life support, search and rescue and DRRM.

The school’s Batang Emergency Response Team (BERT), composed of students working in shifts, has won several awards in DRRM competitions and camps at the regional level.

This year, the Muntinlupa Schools Division recognized the PEDHS as best implementer of disaster mitigation initiatives and strategies among secondary level schools in the city.

In June 2015, representatives from the PEDHS met with homeowners from the nearby subdivisions of UP Side and Hi-Way Homes to discuss the West Valley Fault and how an earthquake from the fault system can affect the community.

A memorandum of understanding allowing the school to use the community as an evacuation area after an earthquake was signed weeks later.

The agreement also designated UP Side as the holding area for students, teachers and nonteaching personnel. On the other hand, the streets around Hi-Way Homes would be assigned as one-way roads to allow the passage of ambulances and fire trucks.

“It’s out social responsibility,” Cabanting said. “We cannot ignore the community (because) we cannot do this alone.”

Meanwhile, at the AES, the school has painted evacuation lanes where students can be assembled and organized by year level and section. Earthquake drills are conducted twice a month.

“What’s great about our kids is that they don’t need their teacher to tell them what to do,” Linquico said. “They hear the siren and they know that there’s a drill.”

The school also encourages its students to produce their own safety gear and first-aid kits at the start of the schoolyear, she said.

Linquico said while teachers are given hard helmets of their own, students are taught to make helmets out of rugs, which they can use to protect themselves from falling objects in the event of an earthquake.

At the start of the academic term, students are asked to buy small bags, where they can store bandages, flashlights, medicine, whistles and food. In addition to the DRRM resources purchased from its own budget for maintenance and other operating expenses, the school receives equipment and kits from the city government, Linquico added.

Evacuation problems

Despite these efforts, the two schools still suffer from the absence of a safe haven within their respective campuses.

While the PEDHS open grounds have been designated as the school’s temporary evacuation site in the event of an earthquake, Cabanting said the grounds are still unsafe and evacuees can get trapped inside the campus should the buildings surrounding the school’s triangular property collapse.

“The evacuation site’s distance from the nearest buildings should be twice the height of these structures,” he added. “But look around, we’re surrounded.”

The PEDHS has only one emergency exit so far, and the possibility of a stampede occurring during an evacuation is high, Cabanting said.

Should electric companies fail to shut down power in the area in the event of an earthquake, evacuating students, teachers and staff will be greeted by collapsed high-tension wires at the school’s main gate.

At the AES, existing risks—large trees and close proximity to the DECS building—continue to threaten the area’s integrity as an evacuation site, Lincquico said.

The school is coordinating with Muntinlupa Mayor Jaime Fresnedi on the purchase of an abandoned lot behind the school. Should this push through, the area would serve as the school’s evacuation site.

Unfortunately, Linquico said this piece of land lies in the middle of a dispute between contending claimants and the local government has yet to determine the real owner of the lot before it makes the transaction.

The school also has still to determine new emergency exits for evacuating students, teachers and staff, given that the fault runs through the school’s only point of entry and exit, she said.

At the national level, school preparedness assessments and safety monitoring tools are still at the drafting level, Marian Aniban of DRRMS- DepEd Central Office said.

No concrete method of assessment has been established, Aniban added, as the safety monitoring tool alongside the framework is relatively new.

Structural integrity, resiliency

Despite the potential risk of structures built on top and along the West Valley Fault, abandoning affected public schools is not seen as either a practical or possible course of action.

Rather, structural integrity and resiliency must be given more attention, according to officials from the DPWH.

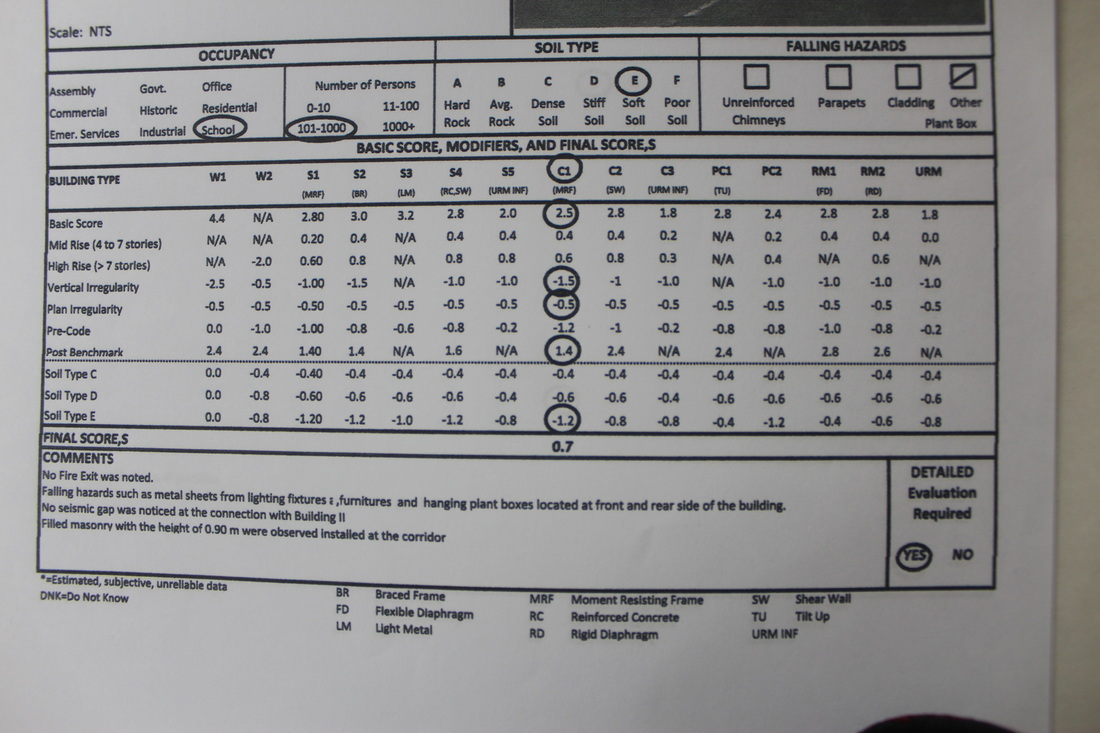

Ricardo de Vera, section chief of the National Capital Region Bridges and Other Public Works division, said following the release of the West Valley Fault Atlas, the department has started a long process of evaluating the structural stability of structures close to the fault, using potential seismic hazards checklists for public schools.

(The authors are University of the Philippines-Diliman journalism majors who produced this piece for Journ 116, Computer-Assisted Reporting, taught by VERA Files trustee Yvonne T. Chua. Some of the data sets used in this report were provided by the Department of Education to the university under the “Data and Society: Applications in Public Education” program supported by the UP Emerging Interdisciplinary Research Program.)