By NORMAN SISON

Sunset photo by BEN LEAÑO

Imagine Manila without a view of its world-famous sunsets over Manila Bay or without a view of the bay itself. Simply unthinkable.

Imagine Manila without a view of its world-famous sunsets over Manila Bay or without a view of the bay itself. Simply unthinkable.

Manila doesn’t rank alongside London, Paris and other great capitals of the world. However, what it lacked in man-made wonders, Manila Bay’s natural beauty made up for.

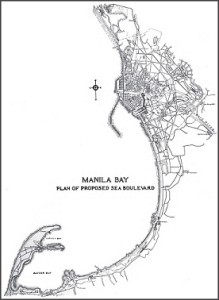

American architect and urban planner Daniel Burnham saw Manila’s potential during a visit in 1905. Commissioned by American governor William Cameron Forbes to draw a city plan for Manila, Burnham envisioned a lovely coastal boulevard stretching 10 kilometers from Intramuros, the original walled city of Manila, to Pasay City to the south.

Cavite Boulevard was to continue all the way to Cavite province. Burnham’s idea was a spacious tree-lined roadway that included a tramline and sidewalks for promenaders.

During the American colonial period, Manila was home away from home for its 5,000 American residents. Tourism promoters then pictured Manila as the “Pearl of the Orient”.

“Americans rose early, spent the morning at their offices, took a siesta after lunch, returned briefly to their desks and quit at four or five in the afternoon,” described journalist Stanley Karnow, in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines, of how life was back then. “They might then listen to the daily band concert at the Luneta (Rizal Park today), go horseback riding along the beach, or play golf, tennis or polo before drinks at their clubs as the sun set in a splash of effulgent colors.”

Over a century later, land reclamations, lack of urban planning and other problems that accompanied urbanization reduced Burnham’s concept to a mere two kilometers, between the US embassy and the Cultural Center of the Philippines.

But Manila Bay’s charm continues to draw promenaders, joggers, bikers, skaters, lovers and families. And each day closes in a spectacular blaze of colors as the sun sets over the horizon — to the delight of photographers and anyone with a cell phone camera.

Manila residents will say that you’ve never been to Manila if you’ve never seen a Manila Bay sunset. A travel article on Time Magazine included “sunset watching” in its list of 10 things to do when in Manila.

Manila residents will say that you’ve never been to Manila if you’ve never seen a Manila Bay sunset. A travel article on Time Magazine included “sunset watching” in its list of 10 things to do when in Manila.

It is that postcard picture of Manila that a motley group of protesters, calling themselves the SOS Manila Bay Coalition, is now fighting to prevent it from becoming history. Their battle cry is “Save our sunset”, and their main opponents, ironically, are the Manila city council and the city government.

It all began in 1991, when the Public Estates Authority (now the Philippine Reclamation Authority) issued a clearance to Elco Development & Construction Corporation, the parent company of Manila Goldcoast Development Corporation, to build on the remaining two-kilometer stretch.

In the following year, protesters won a city council ordinance declaring the remaining two-kilometer stretch off-limits. Also, in 1992, Congress passed a law declaring Manila Bay a national park.

But Goldcoast persisted. In 2011 the city council issued an ordinance giving the project the go signal and the city government entered into an agreement with Goldcoast to help develop the project.

An Internet search reveals nothing on what Goldcoast plans to build. Goldcoast doesn’t have a website, while Elco is listed only in online directories.

In 1954, President Ramon Magsaysay issued a proclamation reserving Manila Bay for a national park. Last year the National Historical Commission declared the Manila Bay waterfront a national historical landmark, protected by law.How a mere city council ordinance could trump a national law has left the protesters wondering. The protest group is circulating a petition on Facebook to torpedo the project.

Being a natural harbor, with an area of 2,000 square kilometers and an average depth of 55 feet, Manila Bay has been the Philippines’ open door to the world.

In 1570, two Spanish frigates commanded by conquistador Martin de Goiti entered the bay, leading to the founding of Manila as the seat of Spanish colonial rule for 300 years.

“As have tourists over the centuries since, they stared with stupefaction at the spectacular sunset,” according to Karnow.

Manila Bay was home to the Spanish ships that plied the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade from 1565 to 1815.

Manila Bay was home to the Spanish ships that plied the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade from 1565 to 1815.

In 1646, Spanish and Dutch warships squared off in the bay during the Eighty Years’ War, ending Dutch attempts to seize the Philippines. The Spaniards attributed the victory to the intercession of the Virgin Mary, and it is commemorated annually to this day in a Catholic festivity known as La Naval de Manila.

In 1898, a US Navy task force commanded by Commodore George Dewey annihilated a Spanish flotilla at the outset of the Spanish-American War, heralding America’s presence in the Philippines.

Cavite Boulevard was later renamed Dewey Boulevard to honor the hero of the Battle of Manila Bay. In the 1960s, the road was renamed Roxas Boulevard, in honor of Manuel Roxas, the Philippines’ fifth president.

The Manila Bay protest group argues that the issue is not just about the view, it is also about preserving history and a national heritage.

“I have childhood memories of going to Manila Bay with my family,” Ayie Zerrudo commented on the online protest petition. “It’s something every Filipino should be able to experience and appreciate.”