By KATRIA AYANNA P. ALAMPAY

WHEN Manang Bolabola came out, there was a new doll in her secret room, with eyes the color of twilight that had been grazed by the twinkle of the first evening star.

WHEN Manang Bolabola came out, there was a new doll in her secret room, with eyes the color of twilight that had been grazed by the twinkle of the first evening star.

Manang Bolabola is a character in Doll Eyes, the award-winning story of Eline Santos, now a book published by the Center for Art, New Ventures and Sustainable Development (CANVAS), a nonprofit organization that promotes awareness for Philippine art and culture.

Doll Eyes takes place amid the colorful and bustling streets of Quiapo on the eve of the Feast of the Black Nazarene, the spectacular religious event held every 9th of January. Thousands of devotees join in the procession, desperately attempting to touch the image of “black” Jesus’ image. Many believe that even a towel that had rubbed the statue is imbued with healing powers.

The protagonist in Doll Eyes is Tin, a street child who seeks to rescue her best friend Ella from the shop of a witch who turns children into dolls.

Manang Bolabola would sit outside her little shop, eyes half-closed, as if sleeping. But the truth was she saw, smelled and heard everything. She was watching and waiting for the right kind of material to make her dolls with.

Witches, soothsayers, manghuhula (fortune tellers) and mangkukulam (faith healers) are not rare in Quiapo. Just a few steps from the historic Plaza Miranda, where, in the past, political fortunes were made and lost, and Quiapo Church—home of the most venerated Black Nazarene statue—churchgoers can avail of horoscopes, palm readings, healing massages and tarot cards right after mass from mystics asking for just small donations ranging from P50 to P500.

One can even avail of the services of professional prayers, people who pray for other people for a fee, who quietly do their business near the church entrance.

Quiapo is the heartland of Filipino superstition. Scapular and rosary sellers mingling with anting-anting (talismans) vendors and palm readers surround Quiapo Church. Filipinos and tourists alike flock to the sidestreets of Quiapo to quench either their beliefs or their curiosity. Some go there for miracles.

Not even the Catholic Church’s condemnation for the practices of fortune-telling and following “false” prophets, could stop Filipinos from purchasing talismans with Latin inscriptions—even during the Holy Week—to repel evil or bring good fortune.

Aside from the supernatural consultations available in the area, Quiapo offers other kinds of services. Felix R. Hidalgo street, where a few remaining old colonial houses give a glimpse of a genteel past, is now a photographers’ haven, with shops offering all kinds of cameras and photo accessories.

In Quiapo: Heart of Manila, Dr. Fernando N. Zialcita, head of the Bahay Nakpil-Bautista Foundation, says, “The heart of major cities abroad is not the shopping mall, not the gated communities but districts like Quiapo, where the rich, the middle class and the poor mix together, where your place of work is close to where you live, where the streets are lively throughout the day, and where there are beautiful historical landmarks.”

Quiapo is a labyrinth of stores that sells everything from the mundane—such as stolen cell phones and seventy-five-peso slippers—to the arcane .

And if you cannot find the store where you once bought a black chicken to make your son grow taller, it might be that the store decided to move—as mysterious stores are likely to do.

Quiapo is a place of ironies and contrast. Faith and fate mix at the doorstep of Quiapo church. The fading elegance of the houses on Hidalgo Street is captured for posterity by photographers. History, evoked by Plaza Miranda, blends with the current and constant, such as Filipino fixation with luck.

The Filipino attitude of “wala namang mawawala kung maniniwala” (“nothing to lose with believing”) plays a key role in our culture of accepting superstition in our daily lives.

Filipino superstition and religion can exist peacefully not only in Quiapo but in the general Filipino society because both belief systems can coexist by respecting each other. The mystical amulets and fortunes can provide people with comfort that perhaps they can even slightly influence their fates or perhaps be guided with some “suggestions.”

That was when Ella noticed that a few of the dolls shifted ever so slightly. She could feel her own fingers bend somewhat though she could not clench them, even in her fear and anger.

What happens when you are forgotten?

Then you are frozen forever. There is no chance of escape.

Like Quiapo, Doll Eyes offers charm, magic and a sense of danger.

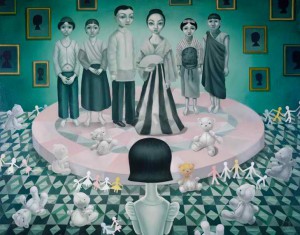

Doll Eyes will be launched in December with an exhibit by artist Joy Mallari of her interpretation of the book.

The 10th children’s book to be produced by the five-year old CANVAS, Doll Eyes was the winner in the 2008 Romeo Forbes Children’s Book Storywriting Competition.

The competition is in honor of Romeo Forbes, who had as his first and only one-man show, an interpretation of Augie Rivera’s “Elias and his Trees” in 2005, organized by CANVAS. Romeo died of cancer in early 2006 at 24.

To honor his memory, CANVAS renamed its annual writing competition as The Romeo Forbes Children’s Story writing Competition.