By RALPH TY

THERE seems to be no stopping the advancement in the country of the controversial stem cell technology that promises effective treatment of cancer and other life-threatening diseases.

THERE seems to be no stopping the advancement in the country of the controversial stem cell technology that promises effective treatment of cancer and other life-threatening diseases.

This despite ethical and moral issues earlier raised by critics led by the Catholic church.

First, there was CordLife’s cord blood processing and storage facility–the first of its kind in the Philippines–that opened at the UP-AyalaLand TechnoHub in Quezon City early this year.

Then came House Bill 1977 filed recently by Rep. Eufranio Eriguel of the Second District of La Union, seeking to establish a stem cell research and storage center in the country.

Eriguel said the center will be mandated to “conduct research under established standards of open scientific exchange, peer review and public oversight.” It could lure investors and make the country a “haven for open scientific inquiry and technological innovation.”

CordLife, the largest commercially-operated network of cord blood banks in the Asia-Pacific region, on the other hand, said its new world-class facility will bring the benefits of stem cells from cord bloods (taken from umbilical cords of infants) to Filipinos.

It said cord blood has become a major source of stem cells (or unspecialized cells) that have been proven to treat over 80 diseases, including certain cancers, bone marrow failure syndromes, inborn errors of metabolism, blood disorders and immunodeficiencies.

To better understand stem cells, the United States National Institutes of Health listed their three distinctive features: First, they can renew themselves and divide into “daughter” cells for long periods of time. Second, they are still unspecialized, which means they do not perform any organ- or tissue-specific function yet. Third, being unspecialized, these cells, through careful scientific manipulation, can eventually become somatic cells.

Much like how the modeling clay provides the flexibility to create any figure or object of choice, stem cells pose the same promise to the scientific and medical communities and to the general public.

Mere fiction?

Although stem cell technology promises to revolutionize medical science, its critics believe otherwise. They even claimed that this technology is actually “anti-life.”

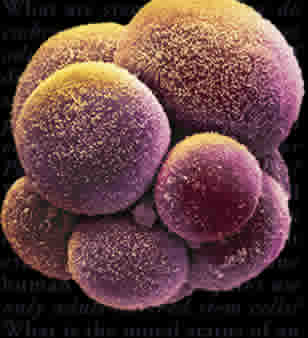

Much of the controversy surrounding stem cell technology arise from the morality of using an embryo–which some already consider as a human being in-the-making–for research and medical purposes.

Some groups, most notably the Catholic Church, have labeled the technology as anti-life because the extraction of stem cells from the blastocyst stage (the earliest stage of embryo development) inevitably means the destruction of the blastocyst, thus stopping it from developing any further.

A blastocyst is basically a ball of unspecialized cells—the stem cells—which will later on develop into a fetus in the womb.

Sidney Auxiliary Bishop Anthony Fisher questioned stem cell technology’s alleged numerous medical benefits at the 2005 International Congress on Bioethics held at the University of Santo Tomas.

He decried the whole “embryonic stem cell panacea” as “merest fiction,” adding it was only “wishful thinking for patients and doctors, and deliberate exaggeration for researches and corporations.”

Another issue raised by critics is immune rejection. They said stem cell transplants can always be “read” by a host body’s immune system as a foreign object — much like how viruses are detected — and be attacked. They said this would complicate, rather than cure, the host’s medical condition.

The new technology involves the two types of stem cells: adult stem cells and embryonic stem cells. The main difference between the two is the source from which they are obtained. Adult stem cells usually come from already matured tissues or organs of the body while embryonic stem cells, as the name suggests, are derived from the earliest stage of embryo development.

The most common examples of adult stem cells are hematopoietic cells, or stem cells that turn into blood cells. They are usually found in the bone marrow and have been used to treat diseases of the blood like leukemia.

While adult stem cells are still unspecialized when extracted, they can only become the cell type of the organ or body part from which they are derived. Embryonic stem cells, on the other hand, are more “flexible” and can be made into any of the 200 cell types found in the body.

In 1998, a team led by Dr. James Thomson from the University of Wisconsin, Madison developed the first culture of human embryonic stem cells.

Embryonic stem cells hold more promise in treating many diseases from cancers and diabetes to more debilitating ones like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases because they develop into practically any type of cell.

Stem cell technology is an exciting new field to explore, but one that faces so many ethical and moral questions. The challenge, therefore, not only lies in improving the current technology, but also in confronting its ethical and moral implications.