“Literacy is a bridge from misery to hope.”

— Kofi Annan

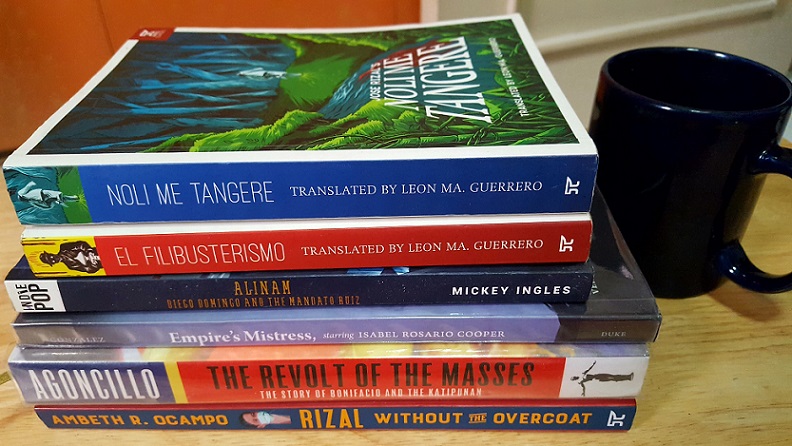

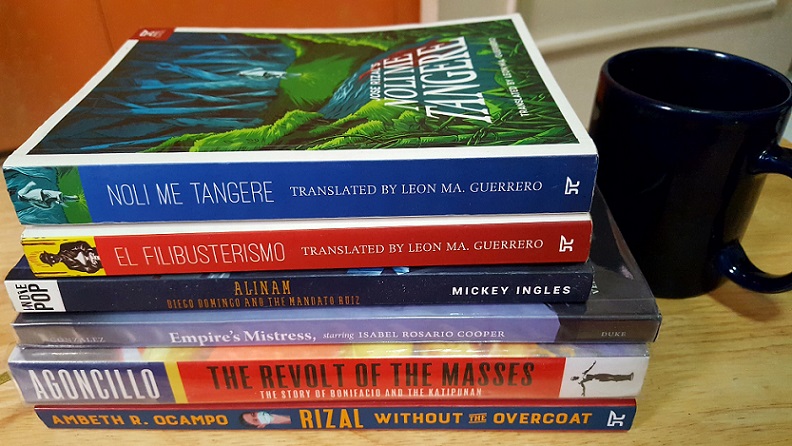

National Literature Month has been celebrated in April in the Philippines for the last eight years, but its avid circle of devotees remains small. Hearing someone not reading is so commonplace these days that the ex-high school teacher in me has been pushed into a frustrated silence. I have no words for a nephew who declared he didn’t bother reading Jose Rizal’s “Noli Me Tangere” in junior high; I was mum when a friend said her cousin, who’s in grade 10, was blasé towards “Noli” and disinterested in “El Filibusterismo.”

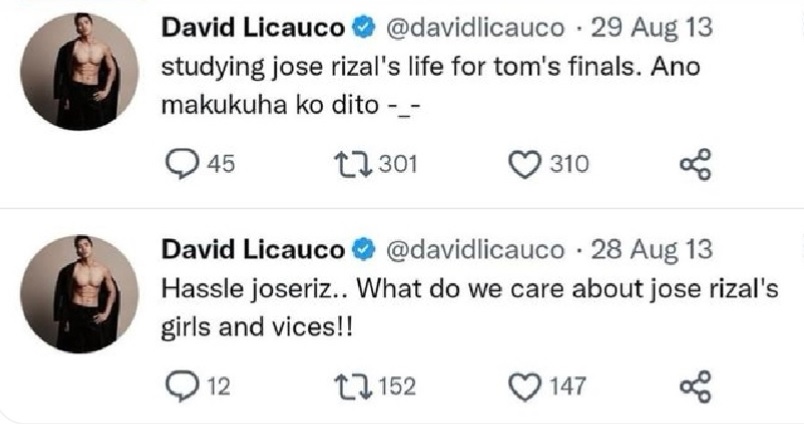

But the teacher in me stirred after reading David Licauco’s two 10-year-old tweets that have resurfaced online, with the Filipino entrepreneur-actor agonizing about reading of Rizal’s life in the first and, in the second, asking what was in it for him in “studying Rizal’s life for tomorrow’s finals.”

The aversion to reading is too much, yet I sighed in sad relief. Seen against the Philippines’ learning poverty, Licauco’s literacy is more than can be said about the majority of Filipino students.

According to World Bank data, the country’s learning poverty was already at 69.5 percent in 2019, quantum leaping to 90 percent in August 2021, and inching up to 90.9 percent by June 2022. Learning poverty is the inability to read or understand a simple text or story at 10, the age that children should be reading because it’s a “gateway for learning…math, science, and the humanities, as [they] progress through school,” said the World Bank, emphasizing that the gateway shuts when children can’t read and, sadly, fail to master it later in their schooling.

The Philippines is hitting rock bottom compared to, say, Malaysia’s 42 percent and Indonesia’s 52.8 percent. It’s unfathomable now how the youth can be the future’s hope, as Rizal once said. Is there hope for the nine out of 10 Filipino youth struggling to read?

A moribund skill

To my mind, Republic Act No. 1425 (aka the Rizal Law), signed by President Ramon Magsaysay on June 12, 1956, could have helped alleviate the country’s perennial illiteracy problem. RA 1425 requires students to read Rizal’s novels, but my naïveté got the best of me.

Reading is moribund, making Antonio Antonio and Justine Tupaz a rarity. Antonio, 45, read half of Rizal’s “Noli,” but finished ” Fili” while completing high school in Jose Abad Santos Memorial School (Jasms), where I taught English classes in the mid-1990s after graduating from the University of the Philippines. Tupaz, 19, read “Noli” in 2018 when he was a grade 9 student at Veritas Catholic School; he remembers some classmates hating “Noli” because they were too lazy to read, “but many of us loved it.” He’s keen to read ” Fili” on his own to know what happened next.

The grim outlook stems from myriad problems, beginning with students not reading. If they do read, the time constraint exacerbates the situation. The old Department of Education (DepEd) curriculum gave a full school year to study the two Rizal novels, compared to the new K-12 curriculum that leaves students and teachers only a quarter period per novel — usually the last one in every school year — to study the literary masterpieces, said Filomeno Aguilar Jr. et al. in “Relational Nation,” an ethnographical study on how students from two public high schools in Rizal province relate to characters in “Noli.”

Making the challenge more daunting is how “Noli” is taught. Aguilar’s study, published in Kritika Kultura 39, said it wasn’t tackled through reading the chapters back-to-back. Instead, chapters emphasizing the characters’ development were selected and prioritized for reading. However, the grade 9 students still didn’t read and relied mostly on their teachers’ lectures, classmates’ reports, and performances in class, as well as the “abridged versions and summaries, movies, komiks, [and] videos that disregarded the original source text.”

Equally problematic is the curriculum’s focus on the characters and the learning outcome of students expressing their “personal emotion” in response to the characters’ situations. The end goal of students expressing themselves is commendable, but personal responses indifferent to the novels’ historical and political contexts lead to complete ignorance of issues and contexts. Students easily succumb to historical revisionism for lack of proper grounding, which can only come from proper and thorough reading.

Tellingly, individual reading and writing skills are stunted as overall learning is gauged through performances — i.e., a movie trailer with students “enacting the key characters” or a storyboard that “deconstructs the characters’ traits in Rizal’s novel.” Group work has only ever resulted in lackadaisical pupils getting passing marks because they piggybacked on the well-read students.

A disturbing reality

That Filipino kids can’t read, as standardized international assessments have concluded, is a disturbing reality. Building reading skills begins with recognizing a single word, and Filipino students are struggling with this. In the 2019 Southeast Asia-Primary Learning Metrics (SEA-PLM), their reading score was 288 out of 300 points, the average of the six countries that participated in SEA-PLM. Further findings showed that only 27 percent could identify relationships between words and meanings in English. Worse, only 10 percent of them achieved the reading proficiency needed at the end of primary education that allowed for easy transition to secondary education.

In contrast, 58 percent of Malaysian students and 82 percent Vietnamese students achieved level proficiency.

SEA-PLM tests grade 5 students in reading, writing, mathematics, and global citizenship from six Southeast Asian countries. Initiated by the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Association and Unicef in 2012, the first assessment was done in 2019; the next round is in 2024.

But the dire warning that Filipino students can’t read was already echoed as early as 2000 when the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) results came out. Bro. Andrew Gonzalez, FSC, then education secretary, had grade 7 and 8 students take TIMSS, which ended badly, according to the FEU Public Policy Center (FEU-PPC). When Raul Roco headed the DepEd, he took the Philippines out of TIMSS. He said it was a waste of funds to pay for expensive testing if the outcome is already known, per the FEU-PPC.

When the students took TIMSS 2003 and TIMSS Advanced 2008, one assumed that their reading skill had been honed. But no. The Philippines placed 34th of 38 countries in math and 43rd of 46 countries in science in 2003, and “ended last among 10 countries” in 2008, said aer.ph.

TIMSS measures what grades 4 and 8 students have learned about math and science from school. The test features short questions focused on facts and processes, and has been administered every four years by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement since 1995.

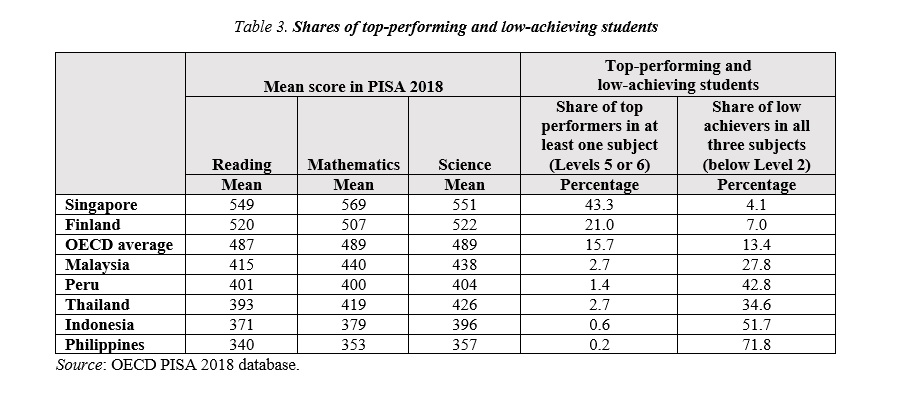

One hoped that the students’ reading proficiency had improved by leaps and bounds when they took the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) for the first time. But no. It was like the TIMSS fiasco all over again. Of 79 countries, the Philippines placed last in reading with a score of 340 against the average of 487, and occupied the penultimate position in science and math, scoring 353 in math and 357 in science, against the average of 489 in math and 483 in science.

Pisa assesses 15-year-old students on their proficiency in math, reading, and science every three years regardless of their school year level. Founded in 2000 by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, the testing for functional skills — i.e., problem solving and critical thinking — is done through real world problems with longer text and instructions.

Undeterred by the Pisa results, the Philippines once more participated in TIMSS 2019 covering 64 countries after a 16-year-absence. This time only grade 4 students took the exam. History repeated itself. Of the 58 countries that only had grade 4 students tested, the Philippines placed last, scoring way below the average of 400: 297 in math and 249 in science.

‘In the flickering lamplight’

Reading is the exercise of the mind, and Philippine heroes Andres Bonifacio and Rizal recognized this wisdom. Bonifacio read the history of the French Revolution, Rizal’s novels, Alexandre Dumas’ works, and books on international law and medicine “in the flickering lamplight…in between making and selling canes and paper fans, and making posters for business firms,” said historian Teodoro Agoncillo in “The Revolt of the Masses.”

Dr. Pio Valenzuela acknowledged Bonifacio’s voracity as a reader when he “mediated” an exchange of opinions between Magdalo faction member Daniel Tirona and Bonifacio — a Magdiwang follower — on the subject of revolution, where the former became heated while the latter remained calm.

“I know, Don Daniel, that you’re more educated than Don Andres, but when it comes to the history of revolutions, I think that you have yet to read all the books he has read on the subject before you can successfully defend your side,” Valenzuela, Bonifacio’s ilustrado friend and compadre, said, as quoted by Agoncillo in “The Revolt of the Masses.”

Rizal read French literature in Spanish translation, books on the Philippines, etc., and his family had one of the biggest libraries in Calamba — a rarity in 19th-century Philippines, said historian Ambeth Ocampo in “Rizal without the Overcoat.”

Reading was the foundation of my English and writing classes when I was teaching in high school, much to the chagrin of my students, their parents, and my colleagues. The latter had me nonplussed when I learned that they absolutely hated reading. But why? Children — and adults — who read have a great advantage over non-readers. They possess, among others, improved vocabulary, better comprehension, sharpened critical thinking skills, and enhanced analytical and writing skills, as listed by youngreadersfoundations.org.

Building the habit

Reading wasn’t a problem, at least based on my experience in Jasms — which I attended from grade school to high school — except for our Filipino class where we had to read Rizal’s novels in Tagalog from cover to cover. (To comply with the assignment, I read Leon Ma. Guerrero’s English-translated versions. I recently reread the same versions.) Some of my classmates griped about school, but they always buckled down to reading. Basically, everyone read, but with some reading more than the rest.

My own habit of reading was built steadily at home and throughout grade school, involving a lot of library time, reading assignments, writing book reports, completing the SRA reading program, and a Jasms Book Club (JBC) membership in grade 7. Joining JBC was mandatory in order to graduate from grade 7 and enter high school. Each student was assigned five cards in various colors, which we had to complete by reading the number of books per card within a year or before graduation in March. A student librarian monitored the borrowing of books and signed off the cards when the quota of books was met.

Our grade school teachers prepared us for more complex reading in high school and beyond. In high school, through Rizal’s novels — backed by knowledge on Philippine history from Ms. Julie Alcantara’s grade 6 social studies class — the Philippines’ colonial past and fight for independence, current events, and the interconnectedness of the subjects (i.e., literature, arts, social studies) were discussed.

Like my generation, Antonio and Tupaz came to understand the Filipinos’ sufferings under Spain. Antonio, now US-based, credits his teacher for highlighting “the abuse of power of friars and colonizers,” leading him to discern how the absence of unity among Filipinos in fighting the oppressors led to the eventual failure of the revolution.

“I liked the novel personally. It opened my eyes to our history and the struggles that the Filipinos experienced. To be honest, those who grew up to understand the novel liked it, while those that didn’t don’t care at all,” Antonio said in a recent interview.

Prepping the class

The 2018 Pisa results alone highlight the urgency in upgrading Filipino students’ literacy level. Reading should be taught and encouraged if Rizal’s words are to ring with veracity. But the job doesn’t fall on the teachers alone, contrary to popular opinion. Parents must be tasked to make the home conducive to reading, which doesn’t happen by osmosis. It’s a skill that needs to be built and practiced constantly. Reading at home, where children spend more time, will help them progress quickly in school as they move towards more complex reading tasks.

Significantly, leaders and policymakers should prioritize reading over undergoing military service training. Education, as Rizal advocated, is the way to eradicate ignorance and servitude. However, in fixing the reading problem, pertinent issues must be addressed, like teachers’ wages. The Alliance of Concerned Teachers (ACT) is lobbying for the passage of House Bill No. 203, which seeks to upgrade the salary grade (SG) of entry-level public school teachers from SG11(roughly P25, 439) to SG15 (P35, 097). With this, teachers can fully concentrate on teaching — and reading — without worrying about finding another means of livelihood to augment their low pay.

ACT has also pressed for the approval of House Bill No. 1783 (aka Education as Priority in the National Appropriations Act) in increasing the education budget by 6 percent. A larger budget can help build more classrooms and provide instructional and learning materials for teachers and students.

Teacher training is another crucial factor. FEU-PPC recommends that the DepEd “refocus and strengthen teacher pre-service and in-service training” on reading and writing, and to pare down the curriculum’s competencies to be achieved. Instead, more time must be given for rumination and problem-solving practice.

The focus can fully shift to upgrading the classroom when teachers’ issues have been fully addressed. Picking up from the devastation caused by Covid-19, an intensive literacy program must be drawn up similar to, as I see it, my Jasms days. Prioritizing teaching fundamental skills is in line with Unicef’s Five Key Actions for Education Recovery, which can help students achieve the SEA-PLM standard of reading proficiency. Dovetailed with this are Unicef’s two other key actions: reaching and having each child attend school, and “developing psychosocial health and well-being so every child is ready to learn.”

Complementing Unicef’s plan is Senate Bill No. 150, or the Academic Recovery and Accessible Learning (Aral) program, proposed by Sen. Sherwin Gatchalian. If approved and executed well, Aral will assist students struggling academically to catch up with the world, according to pna.gov.ph. With an initial budget allocation of P20 billion, Aral will tackle learning competencies in language and math for grades 1 to 10, and science for grades 3 to 10. It’ll build the literacy and numeracy of kindergarten students.

Filipinos were the intelligent, critical thinkers of the Asean community more than half a century ago. Lamentably, these days they’re only known as the loudest K-pop fans and pop concert goers in the world. It’s not too late for the nine out of 10 Filipino students unable to read to lead the pack again. They have to go back to basic reading; there’s no shortcut to it.

ASEAN Countries Learning Poverty Data

| COUNTRY NAME | LEARNING POVERTY (%) | INTERNATIONAL ASSESSMENT |

| Brunei Darussalam | No assessment | No assessment |

| Cambodia | 90 | 2019 SEA-PLM |

| Indonesia | 52.8 | 2015 TIMSS |

| Lao PDR | 97.7 | 2019 SEA-PLM |

| Malaysia | 42 | 2019 SEA-PLM |

| Myanmar | 89.5 | 2019 SEA-PLM |

| Philippines | 90.9 | 2019 SEA-PLM |

| Singapore | 2.8 | 2016 PIRLS* |

| Thailand | 23.4 | 2011 TIMSS |

| Vietnam | 18.1 | 2019 SEA-PLM |

*The Progress in International Reading Literary Study measures the reading achievement at grade 4 every five years.

Source: “The State of Global Learning Poverty: 2022 Update” by World Bank, UNICEF, FCDO, USAID, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, in partnership with UNESCO