Photos from Presidential Development and Strategic Planning Office courtesy of the Gerry Roxas Foundation.

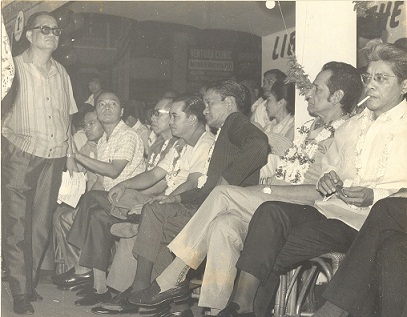

It was at 9:13 p.m. when the Liberal Party’s candidates for the Senate and for mayor of Manila presented themselves onstage at a midterm election campaign rally in Manila’s Quiapo district. It was August 21, 1971.

For months, President Ferdinand Marcos was being rocked by corruption allegations, including accusations of cheating in the 1969 presidential elections, where Marcos won a second term. All eyes were on the Liberal Party rally at Plaza Miranda, fronting the Spanish colonial-era Quiapo Basilica.

“Rumors had swept Manila’s coffee shops all week that the opposition candidates were planning to document onstage the graft and corruption which riddled the Marcos government,” according to American journalist Sandra Burton in her book Impossible Dream, which documented the 1986 overthrow of the Marcos dictatorship.

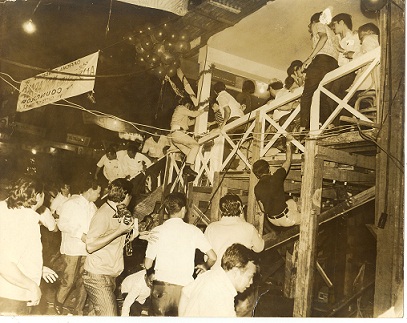

Liberal Party president Gerardo Roxas had just introduced the lineup to a crowd of about 4,000 when a grenade explosion rocked the stage. Another attack seconds later tore through the scene.

Nine people, including a five-year-old child, were killed, and over 90 were wounded in what went down in history as the Plaza Miranda Bombing. The attackers were never caught.

A cameraman captured the attack in a grainy video, viewable today on Youtube.

As expected, the Liberal Party suspected Marcos of masterminding the attack. Marcos, meanwhile, accused his chief nemesis, Senator Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., of orchestrating it with communist rebels. To this day, Jose Maria Sison, the self-exiled leader of the Communist Party of the Philippines, denies responsibility.

A 35-foot high marble obelisk, topped with a statue of a woman holding a torch at Plaza Miranda, is all that reminds passersby of what happened there 42 years ago. Some historians mark the bombing as the start of the Marcos dictatorship.

Today’s generation of Filipinos find it difficult to fathom how the 5,300-square meter Plaza Miranda figured prominently in the nation’s political history or why politicians of long ago held rallies in what is now a suffocating venue in a megapolis choking in people and traffic.

The square was named after Jose Miranda y Sadino, a Spanish official who served as secretary of the treasury from 1833 to 1854. An 1898 map of Manila — meaning the 0.67-square kilometer Spanish citadel of Intramuros — and its surrounding areas placed Plaza Miranda at the heart of Quiapo. The centerpiece was — and still is — the Quiapo Basilica, home of the Black Nazarene, a statue of Jesus which draws thousands of devotees.

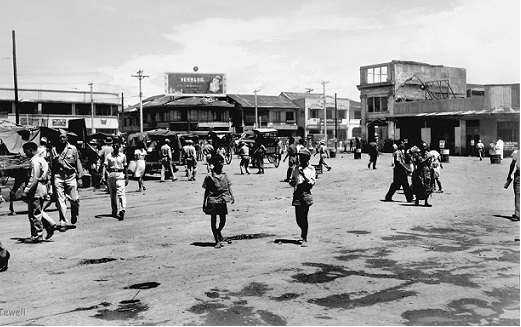

A rare turn-of-the-century photo shows a Plaza Miranda, relatively quiet by today’s standards, occupied by calesas or horse-drawn carriages. Decades later, the square became a regular venue for political campaign rallies, making it the center of political debate — Manila’s tiny version of New York’s Times Square or London’s Trafalgar Square.

A rare turn-of-the-century photo shows a Plaza Miranda, relatively quiet by today’s standards, occupied by calesas or horse-drawn carriages. Decades later, the square became a regular venue for political campaign rallies, making it the center of political debate — Manila’s tiny version of New York’s Times Square or London’s Trafalgar Square.

In the 1950s, President Ramon Magsaysay’s made Plaza Miranda a litmus test of public policy and accountability with his immortal line: “Can we defend this in Plaza Miranda?”

Owing to its history as a forum for free political discussion, Plaza Miranda is designated a “freedom park”, one of a handful of places where political rallies may be held without a permit from the authorities.

In today’s online age, Filipino liberals have likened the Internet as a “cyber Plaza Miranda” because of the freedom it affords to ordinary people to speak out their mind. Muzzling the Internet, they say, is a throwback to the Marcos dictatorship.

In today’s online age, Filipino liberals have likened the Internet as a “cyber Plaza Miranda” because of the freedom it affords to ordinary people to speak out their mind. Muzzling the Internet, they say, is a throwback to the Marcos dictatorship.

As Metro Manila exploded into a megapolis through the decades, Plaza Miranda was reduced to a tiny corner as it was swallowed up by unchecked urban decay. It is a sea of passersby, churchgoers, bargain hunters, vendors, beggars, pickpockets and fortune tellers selling lucky charms and amulets — all oblivious to its history.

On that fateful night in 1971, Aquino, the father of current Philippine president Benigno Aquino III, was scheduled to speak at the Liberal Party’s miting de avance. But he was held up because of a wedding reception. Marcos, the father of Senator Ferdinand Marcos Jr., pinned the bombing on Aquino, pointing out that he was absent at the rally.

Using the attack as an excuse, Marcos cited a purported communist rebel plot to destabilize the government. He assumed emergency powers and suspended the writ of habeas corpus. A year later, on September 21, 1972, he declared martial law.

Aquino was jailed for seven years and seven months until he was allowed by Marcos to seek medical treatment in the United States in 1980. In June 1983, Aquino announced that he was returning to Manila to confront Marcos.

Aquino was jailed for seven years and seven months until he was allowed by Marcos to seek medical treatment in the United States in 1980. In June 1983, Aquino announced that he was returning to Manila to confront Marcos.

In mid-July he got word that the government had supposedly uncovered an assassination plot. He initially set his return for August 7, but was urged by then Marcos defense minister Juan Ponce Enrile to delay by at least a month, according to Burton in her book.

Aquino deliberately reset his return for August 21, the 12th anniversary of the Plaza Miranda Bombing. “That date had malicious significance that would not be lost on Marcos,” wrote Burton.

Aquino also knew the risk of returning from exile. He told Burton and other reporters who accompanied him on his fateful China Airlines flight to Manila: “My feeling is we all have to die sometime. If it’s my fate to die by an assassin’s bullet, so be it.”