By ELIZABETH LOLARGA

Photos courtesy of Ayala Museum

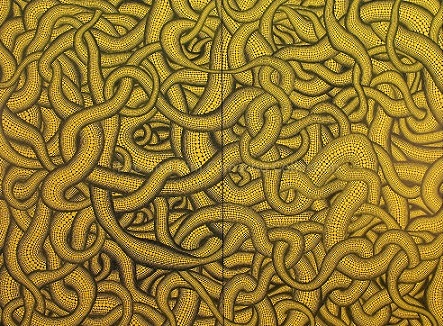

SPIDERY webs, nets, dots, petals–imagine these harmless images. But they’re out there, crowding one’s field of vision, encroaching on, about to engulf one’s self. These hallucinations continue to visit Yayoi Kusama, called “The Queen of the Polka Dots” in the avant-garde world. Rather than being crippled by this psychosis, she has put these repetitious patterns on what are now considered great artworks.

Lito and Kim Camacho have lent their Kusama collection to Ayala Museum. Covering 60 years of the artist’s life, it includes drawings, paintings, collages, sculptures, prints, fashion merchandise like scarves and underwear.

The Japan Foundation flew in Akira Tatehata, poet, critic of modern and contemporary art and leading expert on Kusama, to give a lecture on her life and her unique art.

Kusama was born in Nagano to a family renowned in business, politics and foreign affairs. While she wanted to be relieved of her fears and express them in art, her dominating mother wanted her charming, beautiful daughter, who had many suitors, to marry into a good family.

Due to this conflict, Kusama moved to Kyoto to study nihonga, a conservative style of painting that didn’t suit her. She continued to draw and paint her way, incorporating her reality of dots and webs. In the ’50s when she arrived in New York City, the young, unknown artist went to the top of the Empire State Building and declared with conviction, “I am going to conquer this city.”

Tatehata said Kusama experienced her first success in the ’60s while continuing to paint in the same way, filling up canvases with variations of simple dots and nets. She was never bored no matter how many times she did them. The gaps between the patterns are thick, thin, never the same. The works, he said, give “an illusion of movement–forward, backward, sideways.”

Even abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock raved about her.

Kusama seemed steps ahead of pop artist Andy Warhol in her use of ready-made and cheap materials like air mail stickers stuck all over her collages. She went into soft sculpture, ahead of its so-called forerunner Claes Oldenburg, using cotton as stuffing, sewing together phallic images all over an armchair. This prompted a critic to say that her work “could have just been picked up from the garbage.”

She crammed a step ladder with several phalluses and some high heels. This was interpreted as her statement on a man’s world: everyone was on a race to go up the ladder of success and ambitious women stepped on others to get ahead. Tatehata pointed out that the heels leaned diagonally as though about to fall and belied people’s view of Kasama as a feminist.

He said she didn’t want to be identified with feminism. It represented her mother who headed the clan and was considered a strong woman in their area, but she prohibited Kusama again and again from going into art.

In Japan she earned a reputation as a freak. Among other performances, she led a nude parade of anti-Vietnam war protesters, pretending to have sex with sculptures at an open plaza. Her reputation as “Scandal Queen of New York” prompted her family to stop sending her an allowance.

In the ’70s a young Tatehata saw a small exhibit of hers that left him shaking in awe and thinking, “That’s genius!” He said the genius of Picasso and David “is very close to how I see Kusama,” adding that what they have in common are a stinginess in love for or from family and the lack of preparation or tests before creating a work.

He said, “They do what they want, they’re cool about it, they march to a different beat. Kusama is not of this world. The way she thinks is out of this world. She may not have been given good relations with her family, but as a human being she has a big heart full of love. One of the things I admire about her is her need to have salvation, to lead everybody to salvation.”

At 84, she still struggles with those early visions, with a suicidal tendency manifested in dots that seem to obliterate the self. Tatehata said her art enables those who’ve experienced it “to sympathize with the challenge she’s having, to share with her way of thinking.”

After the March 2011 tsunami, Kusama organized a charity event for victims and survivors that showed her genuine love for everything she does. No wonder she is known by the tagline she uses to sign some works with: “Love forever.”

(A special screening of Kusama films with an evening exhibition viewing is set on Aug. 22 at the museum. The exhibition at Ground Floor Gallery and Third Floor Glass Lane is on until Sept. 1.)