By MYLAH R. ROQUE

EVEN as the country reels from the killing of Dutch aid worker Wilhelmus JJ Lutz Geertman, a Swiss couple who has lived and worked among Manila’s urban slum dwellers for over 10 years returns to share their story.

EVEN as the country reels from the killing of Dutch aid worker Wilhelmus JJ Lutz Geertman, a Swiss couple who has lived and worked among Manila’s urban slum dwellers for over 10 years returns to share their story.

Christian and Christine Schneider are white but they speak Filipino as if they were born and raised here. Like the slain Geertman, they are perhaps, more Filipino than most.

Pastor Dennis Manas, executive director of Onesimo Foundation which the Schneiders founded, said locals are often awestruck upon meeting them for the first time. Eventually they fall in love with Christian or Christine not because they are both tall and good-looking with blue eyes, but because they are foreigners serving the Filipino people.

In 1988, Christian left the prosperous city of Basel, Switzerland (home of the world’s biggest pharmaceutical companies and some of the best museums) to live in Caloocan’s Bagong Silang resettlement area (home of urban migrants ejected from other areas in Metro Manila).

A trained nurse, he had earlier visited Manila as part of a missionary group who “lived in complete American luxury” inside guarded villages. Christian later became impressed with the work of another group of missionaries, Servants Asia, who “learned the language of the Filipinos and formed friendships with their neighbors in the slums.”

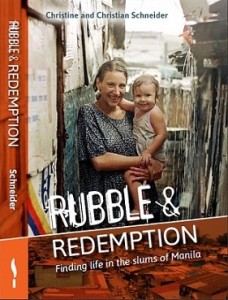

In “Rubble and Redemption,” Christian and Christine tell for the first time the story of how they found life in the slums of Manila. It spans Christian’s experience when he was still a bachelor living in the slums, his long-distance romance with Christine, her decision to join him and raise two children in Manila, and their return to Switzerland.

The book describes squatters’ life under four Philippine Presidents, when extreme poverty and violence were literally outside their door.

It narrates Christian’s encounter with youth involved in drugs and how they are forced to engage in all sorts of activity to finance the vice. It also tells of the rape and violence to children and women and how these had inspired him to help lead teenagers to a life away from the slavery that permeates the slums. This was also the inspiration for Onesimo Foundation, named after the runaway Roman slave Onesimus who became a friend of the apostle Paul.

By the time the Schneiders left Manila, they have built five youth rehabilitation shelters in the same five slum areas where they had lived, a camp in Mindoro where urban youth go during the summer, and a skills training center for adults.

Today, the foundation operates eight shelters in Quezon City’s Payatas, Mendez, Baesa, Kaingin, Philcoa (2) and F.Carlos, as well as Tondo and Quiapo in Manila.

The book is a very honest recollection — of their sincerity to help, the preparations Christian undertook before the trip but which still did not prevent his frustration and helplessness, Christine’s culture shock and frequent worries on Christian’s well-being, the physical dangers they encountered every day, including Christine’s near-death experience from dengue and a subsequent depression, and Christian’s feeling of betrayal over some trusted friends’ mishandling of the funds for a project.

On the morning of July 10, 2000, the Schneiders were the only foreigners among the 300,000 inhabitants of “Lupang Pangako” in Payatas, Quezon City when the 90-foot high and mile-long garbage collapsed.

The book reminds the reader about aspects of Filipino life that are common but which the European finds extraordinary, such as living in a room which is the “bedroom, dining room, kitchen — everything at once,” and Christine’s happiness when residents dug a hole for a water pump so they no longer had to fetch water in kettles far from the house.

Christian’s accounts were sometimes tinged with deprecating humor, like the time he learned belatedly that their new landlord was the biggest drug dealer in the area, that his wife was addicted to crystal meth (a drug that stimulates the central nervous system) and that the reason they sought a big advance on their rent was to pay the bail bond for the husband who was arrested for procuring clients for an underage prostitute.

Christian’s rich narrative also includes experiencing the effects of the explosion of Mt. Pinatubo, and of his long and hot trek in the mountains of Camarines Norte to accompany a friend looking for his brother who had joined the New Peoples Army.

In Basel, Christian now works as a nurse in a hospital while Christine is a school teacher. Before they left Manila, they turned over management of the foundation to a staff of Christian professionals. The couple, however, continues to help raise funds in Switzerland for Onesimo and visits Manila regularly.

Their two teen-age children, Isabel and Noel, describe themselves as “third culture kids” which, according to Christian means that while they find Switzerland more beautiful, “they only feel really well in the tempo, the noise, and the tumult of the people in Manila.”

A few months ago, Christian was diagnosed with dilative cardiomyopathy, a heart disease which could hopefully be slowed down through aggressive drug therapy.

“Rubble and Redemption” will be launched on Thursday, July 19, 6p.m. at Galerie Hans Brumann, Third Level, Greenbelt 5, Legaspi Street, Makati City.