By PABLO A. TARIMAN

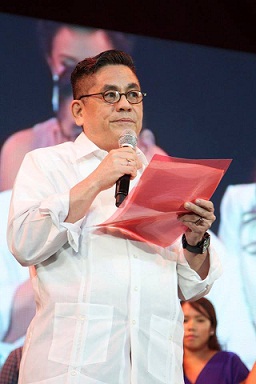

EVERYONE in the theater circuit agree that the Philstage Gawad Buhay life achievement award in theater for Felix “Nonon” Padilla was well-deserved.

EVERYONE in the theater circuit agree that the Philstage Gawad Buhay life achievement award in theater for Felix “Nonon” Padilla was well-deserved.

Padilla started in Philippine Educational Theater Association (PETA) in the company of Lino Brocka and Cecile Guidote Alvarez in the 70s but he actually debuted as stage director in 1968 in the Dulaang Sibol Contest launched by noted theater advocate Onofre Pagsanghan at the Ateneo de Manila.

The play was “Hoy, Boyet” written by Tony Perez and it didn’t fit the usual formula for standard drama at the time.

Recalled Padilla: “The play was experimental with a rather baroque text, free verse that internally rhymed, complemented with a visual language of dance movement and colorful, fairly abstract costumes. It was a play about a teenager contemplating Death, the different forms of love as experienced by a young man, and a dream about his fears and anxieties of facing Time Future and the new world of adulthood.”

The play placed third with the Paul Dumol play getting the plum award. But Padilla had what looked like his comeuppance when the likes of J.D. Constantino, Alfredo Roces, and Bien Lumbera, hailed their play as the most exciting production in Manila with Tony Perez being heralded as a new Balagtas.

Not one to join theater bandwagon and armed with a clear vision of how a theater company should be ran, Padilla recalled his artistic disagreements with famous personalities in his acceptance speech.

Over at PETA in 1972 in the company of Lily Gamboa as chairman and with Brocka as executive director, Padilla was also artistic director of Kalinangan Ensemble.

“From the beginning, our passion was to establish a repertory company of actors, much like the Royal Shakespeare Company, or the British National Theater, or the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It didn’t take long for Lino (Brocka) and myself to clash over choice of plays. I wanted to concentrate on the classics. He wanted popular plays. Those were the Marxist years when every choice had to have relevance to political life. And nationalism was defined by the sickle and the hammer.”

“From the beginning, our passion was to establish a repertory company of actors, much like the Royal Shakespeare Company, or the British National Theater, or the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It didn’t take long for Lino (Brocka) and myself to clash over choice of plays. I wanted to concentrate on the classics. He wanted popular plays. Those were the Marxist years when every choice had to have relevance to political life. And nationalism was defined by the sickle and the hammer.”

He took a respite from theater and tried an alternative career as visual artist and printmaker.

In 1987, he founded CCP’s Tanghalang Pilipino and started the Actors’ Company that produced the likes of Nonie Buencamino, Pen Medina and John Arcilla, among others.

Recalled Padilla: “For 16 years, we managed to present an average of 6 to eight plays per season. In one season we managed to do twelve plays. Budgets were always tight. Even if we wanted to expand training program, hire more teachers and directors, we had to double up functions to make ends meet.”

But the changing of the guard also took its toll in the theater company with the coming of new political appointees running the CCP.

The company survived four presidents and with every changing of the guard, Padilla said the CCP was transformed not exactly for the better, but for the horror of him seeing an art institution eventually turn into a shell run efficiently not by artists but by politicians and bureaucrats.

Padilla farther recalled: “I need not review the horror of those years, but suffice it to say, much energy and saliva have been expelled toward organizing the CCP Art Institution into a well-oiled machine, subject to the whims and caprices of political appointees, who should have done better had they learned to bake pastries or pasta putanesca, than dabble in gossip in the board rooms.”

The last straw that broke Padilla’s artistic composure was when the new CCP dispensation allotted a whopping P1.3 million to produce a gay version of Nick Joaquin’s “Portrait of the Filipino as an Artist” starring Behn Cervantes and Anton Juan in the lead roles of the Marasigan sisters.

The last straw that broke Padilla’s artistic composure was when the new CCP dispensation allotted a whopping P1.3 million to produce a gay version of Nick Joaquin’s “Portrait of the Filipino as an Artist” starring Behn Cervantes and Anton Juan in the lead roles of the Marasigan sisters.

The amount was already the budget of Padilla’s Tanghalang Pilipino for eight productions per season at the Huseng Batute and CCP Little Theater venues.

Padilla said he was scandalized and so was the playwright who maintained a stoic silence watching the two-week run of the new version of the Nick Joaquin classic.

“To be serious about theater,” Padilla pointed out, “one can only look to the rest of the world, to Tokyo, Beijing, Paris, Berlin, and London. All these centers have centuries of theater tradition and the best of them were founded not by bureaucrats and politicians but by theater artists—writers, actors, managing their craft, developing actors not as quickie endos, but as members of a company. Shakespeare, Moliere, and even the Russian consumptive, Anton Chekhov had such a company to rely on and work for. If we are serious about nurturing our culture, we would focus on the ills that hamper the growth of theater in this country.”