Pablo Virgilio Cardinal David has asked visitors to his Facebook page to spare 10 minutes to read what happened to Dion Angelo Dela Rosa.

I’m devastated. I’m at a loss for words to say anything.

The irony of injustice: Flooding, Gambling, and the Death of a Young Man

It was one of those nights when the streets of Malabon and Navotas seemed to have merged with the rivers and the sea. The heavy monsoon rains had returned, and with them the familiar fear of floodwaters slowly creeping into homes. But that night, it wasn’t just floodwaters that disappeared—it was also a father.

On Tuesday, July 22, the father of six children did not come home. The children were used to floods but not to this mysterious disappearance of their father. The whole family began to worry. The eldest, Dion Angelo—known at home as Gelo and among his fellow altar servers at Señor de Longos Mission Station as Dion—searched the streets with his mother Jennylyn, who is disabled (blind in one eye). They asked around, wading through filthy waist-deep floodwater in some areas, filled with fear and anxiety.

They had no idea that Gelo’s father had been arrested without a warrant and was detained for allegedly violating PD 1602—accused of engaging in illegal gambling. He was supposedly caught playing kara y krus. This law against illegal gambling, passed during the time of the late father of the current president of the Philippines in 1978, was said to be a protection for the poor against the vice of gambling. Yet decades later, not a single major gambling lord has been arrested. The poor remain the only victims of this law—just like during the Tokhang days, when quotas on drug suspects became the ticket for promotion.

Here lies the painful irony: while the poor are being charged for playing kara y krus, we are powerless against the biggest operator of the gambling business today through online gambling: the government itself, through PAGCOR. In the past, the government was strict about the public accessibility of gambling. By law, slot machines were not allowed in supermarkets and crowded places. Casinos even had to hire bouncers to check minors and those who could not prove that they earned at least 50,000 pesos a month. Now, gambling can be accessed on every cellphone. Anyone can gamble in their bedroom, on a jeepney, or in bed—24/7. One can even borrow gambling money from GCash.

Why would the police even bother arresting someone playing kara y krus when even children can gamble on their phones before they learn how to multiply? If gambling is addictive, then the biggest pusher of gambling addiction today is none other than our own government through PAGCOR—supposedly to generate extra income for public spending.

We had just released a pastoral letter from the CBCP against online gambling entitled “A Statement on the Moral and Social Crisis Caused by Online Gambling.” A few days later, I released another pastoral letter for the Diocese of Kalookan about flooding and corruption in public works entitled “When the Waters Rise and the Truth Drowns.” I did not know that in the tragedy that would befall Gelo’s family, the twin problems of corruption from flooding and gambling would intersect.

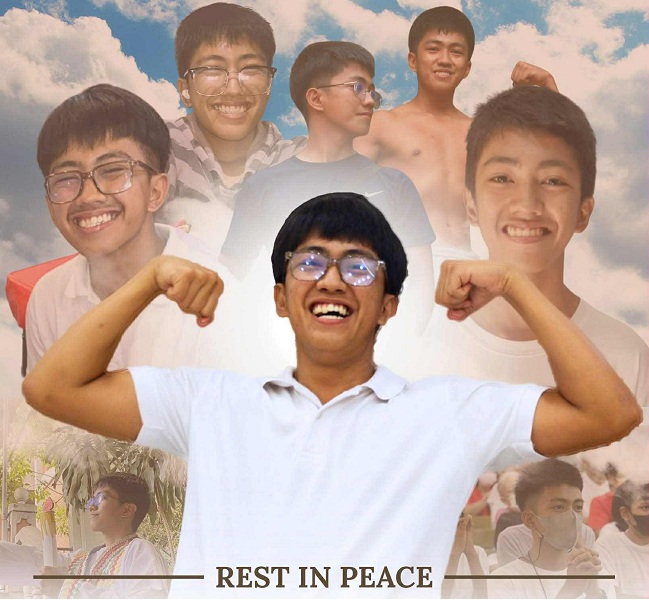

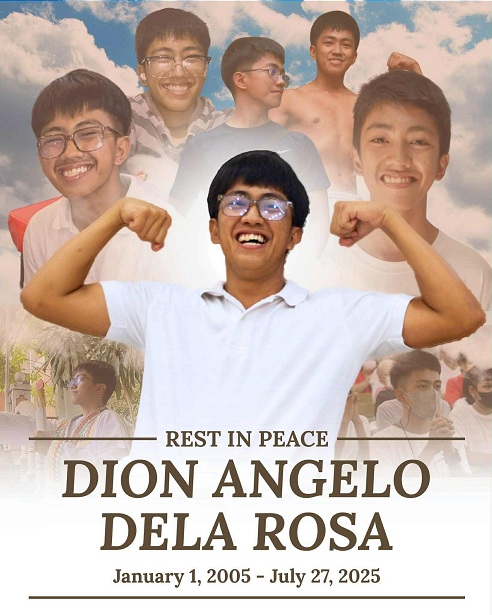

Gelo, 20 years old, a third-year college student, was the family’s hope. Quiet, dependable at home, and a faithful altar server at the church. As the eldest of six siblings, he was determined to finish his Human Resource Services (HRS) course at Malabon City College so he could help his family rise out of poverty.

After 24 hours of no news about his father, Gelo urged his mother to continue the search despite the floods. They went around all the police stations in Caloocan, Malabon, and Navotas, but no one could give them an answer.

The next day, Gelo even separated from his mother to cover more ground and ask more people. He was accompanied by his grandmother, and there they finally found his father in a police station in Caloocan. His heart broke at what he saw: in a small room at the back of the station, his father and five other detainees were handcuffed together. He had gone missing on July 22 and was reported in all the police stations (which routinely share information with each other). But it was only on July 25 that the police admitted they had him in their custody and that he had already been charged on that same day.

From the first day, the father had pleaded with the police to inform his family of his arrest, but they refused. Bail was set at 30,000 pesos—an impossible amount for a family barely surviving their daily needs and school fees. Even the fees for visiting at the precinct weighed heavily on their already meager budget.

So Gelo repeatedly visited his father to bring food and to work on the case. He waded daily through the dark floodwaters until he began to develop a fever on Saturday night. He even apologized to his mother on Sunday morning for not being able to accompany her to the precinct because of his body aches. He also sent word that he would not be able to serve at the Sunday Mass at the new Longos Mission Station church.

His mother told him to take paracetamol and rest. That night, not only was he feverish, but he was also shivering. Yet his main concern remained his father and how they could raise the money for bail. His three-year-old youngest sibling was traumatized when she was the first to discover later that her Kuya Gelo had already died. On Sunday night, July 27, the young man who had been the pillar of hope for his family passed away. The cause: leptospirosis, a disease caused by rat urine in the dirty floodwaters he had waded through in search of his father, who had been arrested for kara y krus.

A cry that reaches heaven

The father was inconsolable when he heard in the precinct about Gelo’s death. Despite his wife’s comfort, he blamed himself. He felt abandoned by God. He did not even know what to do to post bail and return home so he could mourn and bury his eldest son.

Meanwhile, his wife, who is disabled (blind in one eye), and his five younger children kept vigil over the wake that was literally held on the street because they could not afford to rent a commercial funeral chapel for Gelo.

How could this happen? How could a young man’s life be lost due to one misfortune after another? And what choice did they have but to continue wading through the floods when the flood control gate remained broken despite a fresh allocation of 281 million pesos for its repair?

On the other hand, the police continue to meet quotas on arrests under an old anti-gambling law now being used to bully the poor, while rampant online gambling quietly destroys families. How have we become so accustomed to this culture of abuse of power by some law enforcers, who have normalized warrantless arrests and who even pressure detainees to simply admit the charges in court so they could be “absolved” and pay only a 1,000-peso fine—instead of languishing in jail and repeatedly attending court hearings while paying for a lawyer? I wondered: how many thousands of people admit to crimes they did not commit because they have no defense under the law? What has become of the principle popularized by the late President Magsaysay: “Those who have less in life should have more in law”?

The senseless death of Gelo is a parable of our time. His story cries out to heaven—and to all of us. It shouts the question: how many more Gelo’s must die before we confront the systemic injustices that not only destroy livelihoods but also take the very lives of our fellow citizens?

Hope and resolve

As a Church, we cannot close our eyes. We cannot simply be sad and mourn at the wake. We must be the voice of those who have been buried in poverty, ignored by institutions, and silenced by fear.

The life and death of Gelo will not be meaningless. His father has been temporarily released thanks to a kind soul who provided bail money; but he still faces the case. Where will families like theirs turn to? How can they live freely, earn a living, and feed Gelo’s five younger siblings? Who will care for the dignity of his family and work for the change in the justice system that our nation has long awaited, especially for the poor? Heaven will not have mercy on us until justice flows like a river and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream (Amos 5:24).

For now, let us pray for the family. But let us also pray for ourselves—as Christians and as citizens—that the floodwaters of injustice will stop rising and that no more young people like Gelo will be robbed of a future because of the irony of a system that punishes the poor and protects the powerful.