Four search warrants issued by Judge Jose Lorenzo dela Rosa (RTC Manila Branch 4) and two by Judge Carolina C. Icasiano-Sison (RTC Manila Branch 18) were analyzed for their information particulars and adherence to legal protocols. Both judges had issued the search warrants that resulted in the killings and arrests of the Tumandok indigenous peoples of Panay last December 30, 2020 and those of the Calabarzon 9 Bloody Sunday this March 7.

For the record, Dela Rosa had signed search warrants for both the Tumandok and Calabarzon incidents.

For one Luisito Bautista y Castor of Purok 5, Barangay Garangan, Calinog, Iloilo, Sison issued two search warrants: No. 20-30910 for probable cause of violating RA 9516 (illegal possession of explosives) and No. 20-30911 for violation of Republic Act 10591 (An Act of Providing a Comprehensive Law on Firearms and Ammunitions and Providing Penalties for Violations Thereof). In both warrants, the applicant was Police Major Alfonso P. Saligumba III. Luisito Bautista is among those in the list of arrested persons for the Tumandok raids of December 30.

In both warrants, Calinog town is immediately identified as located within Iloilo city instead of Iloilo province, despite the warrant stating that “the place is described in a sketch attached to the application.”

In fact, Calinog is 62.4 kilometers from Iloilo city, a good one hour and 32 minutes by land on the old Iloilo-Capiz highway. What “sketch,” then, did Judge Sison appreciate as police evidence claiming Calinog town was in Iloilo city? At the very least, one of them (she or the police major) failed geography class in elementary school.

Established protocols governing judges on the issuance of search warrants, contained even in ordinary fact sheets by law firms, tell us that “the address in the search warrant must match the actual place to be searched.” In fact, the “particularization of the description of the place to be searched may properly be done only by the Judge, and only in the warrant itself; it cannot be left to the discretion of the police officers conducting the search.” It thus appears that it is Sison who should bear the burden of error in locality. This is not unlike Mayon volcano being transferred to Naga city.

The Sison warrant, in fact, reveals much about careless inadvertency. For two hand grenades, there is no “s” to signify grenade in the plural. This invites the question: Was the computer encoding template used by Sison’s court only for one hand grenade, such that when there is more than one the plural form is overlooked?

In the Sison warrant for RA 10591, the lone witness is not named, and the warrant does not indicate sketches and pictures as exhibits. But an interesting parallel is that the search warrant issued by Dela Rosa for Roy Giganto, who was killed in the Tumandok raid in Tapaz, Capiz, has exactly the same grammatical error of “2 hand grenade.” Yet, Dela Rosa belongs to RTC Manila Branch 4. A question begs to be asked: Is there a common author for all these police search warrants?

In the Sison warrants, no witnesses are named even if it says there are witnesses for probable violations of RA 9516. But the rules of court say witnesses should be named together with the name of the officer who applied for the warrant. Page 2 of the Sison warrant for Bautista presents a puzzle: On the top left where it should indicate pagination, it merely says “Search Warrant No. 20-309, Page 2 of 2.” In fact, it should have indicated whether it is either 20-30910 or 20-30911. Failing that, observers may see doubt in such laxities, one of which pertains to whether the warrants in this sala are fill-in-the-blanks affairs.

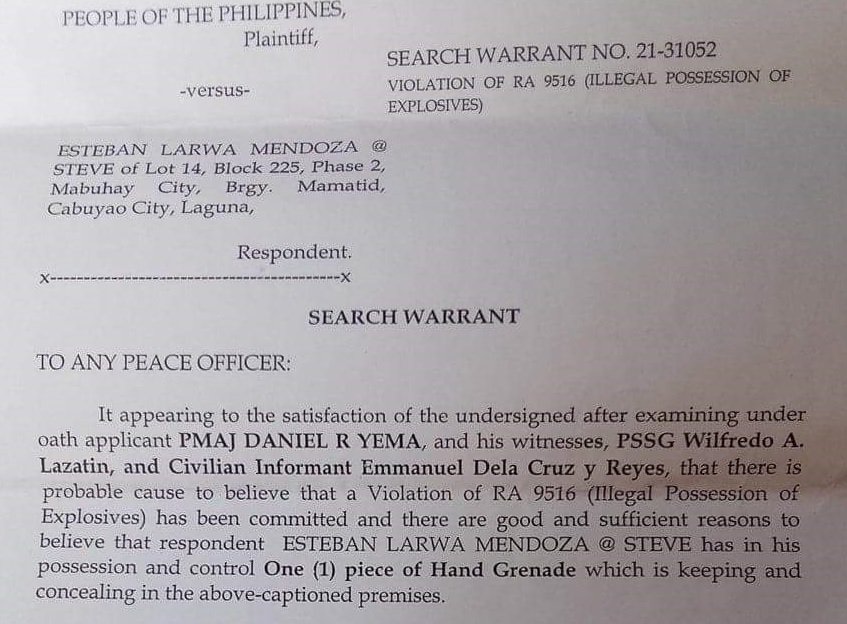

Let us now move to the Bloody Sunday killings by police of the Calabarzon 9, as even Wikipedia now calls the March 7 assassinations. Among those arrested in that well-coordinated multi-location arrests and killings were Elizabeth Camoral y Tabios of Cabuyao, Laguna and Esteban Larwa Mendoza, a labor leader for line industries and agriculture.

Camoral and Mendoza were each subjects of search warrants again issued by Dela Rosa. The judge is a graduate of Ateneo Law, and soon after his graduation, he joined the Ateneo Law faculty, as his faculty profile states, for “being a believer that future lawyers have to be taught that the legal profession is a noble one in order for them to be truly instrumental in helping our country.”

What did Dela Rosa’s warrants command the police? The warrant for Camoral had alleged, “There are good and sufficient reasons to believe that respondent has in his possession and control One (1) piece Hand Grenade which is keeping and concealing in the above-captioned premises.”

Camoral, a woman, was rendered a “he.” Then the grammatical mistake: “is keeping and concealing.” Interestingly, in the search warrant for Marilyn Chiva, a Panay Tumandok arrested on December 30, 2020 that Dela Rosa had also signed, the same grammatical mistake of “is keeping and concealing” was also evident – obviously an attempt to use PRESENT CONTINUOUS TENSE to bolster the continuity of a crime committed. What Dela Rosa means is “it is being kept and concealed” or which the suspect “is keeping and concealing.” Also, Dela Rosa made the female Marilyn Chiva a “he.”

It is obvious that all three warrants emanated from a common Word template. But notice as well that there is a script, and the script being that the police had photographic minds where the objects were concealed, even if the warrant itself cannot even establish where exactly it was concealed.

Even a police study on the application for issuance of search warrants done by PSI Garry Franco C. Puaso maintains in the PNP website: “The place inside the house to be searched must be clearly stated and the address of the house to be searched must be clearly determined. The most important thing to remember in this paragraph is to convince the Judge that respondent owned or if not, has control over the place to be searched.”

“The problem is not just with the template but also with the scripted applications,” says Davao city human rights lawyer A. Dexter M. Lopoz. Last March 13, Lopoz commemorated the death of his younger brother Rex Jasper Lopoz, who was also a lawyer. Rex was killed extrajudicially outside a mall in Tagum city, Davao del Norte in 2019. “Searching for a hand grenade in a small rented apartment has become a script repeatedly used in search warrant applications, supposedly with an ‘eyewitness’ to wit.”

Lopoz makes a powerful point. In all search warrants we had studied from the Tumandok and Calabarzon 9 killings and arrests, police sounded cocksure they knew what goods were being concealed despite the tentativeness of their data. It was clear from all warrants that they could not pinpoint where these were particularly concealed. But given that pompous overconfidence, what do we make of the judges? Did they conspire with the police, and for what cost? Is it because these search warrants are merely semblances of legality because, anyway, the items being searched are planted evidence? In the case of Giganto, operatives merely barged into his house and shot him while he was lying down, asleep. So what was the point of Giganto’s search warrant that purported he was in possession of “2 hand grenade”? Ah, he attempted to hurl the “2 hand grenade” to the police, but police shot him before he could do so? All this while Giganto was snoring soundly, together with his family, perhaps doing a somnambulist “nanlaban.”

The concluding part of a legal document like a search warrant is also called the testimonium because it attests that the signing officer has read the document. Hence, the judge begins with the time-honored line: “Given my hand and seal.” Signing a warrant is a public act because it sets forth an activity that may be penitentiary or have a legal or administrative force or effect. Hence, the warrant is written as a first-person narrative of the signing authority. The judge, as a legal person, signs with the seal of his or her office signifying his or her agreement to the contents of the document. It may sound like minimal mistakes, but a judge attesting to a document with grammatical mistakes is a manifestation of the judge’s substance as a dispenser of verdict. One person who is a she being made a he is by itself a serious factual wrong. That diminishes the judge’s capacity to tell the truth. And warrants, evidence, due process – why, the law itself – is all about the truth, always.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Vera Files.