By ELIZABETH LOLARGA

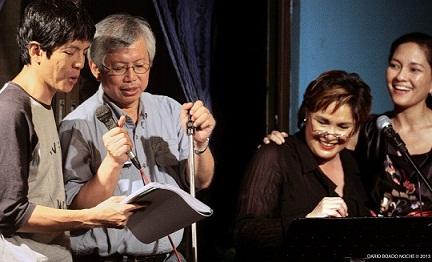

Photos by DARIO NOCHE

Jose Lacaba had a lucky break in journalism in the ’60s when he found himself working with writing icons Quijano de Manila (Nick Joaquin), Kerima Polotan, and Wilfrido Nolledo.

Jose Lacaba had a lucky break in journalism in the ’60s when he found himself working with writing icons Quijano de Manila (Nick Joaquin), Kerima Polotan, and Wilfrido Nolledo.

Before that happened, editor Gregorio Brillantes sent the lad to interview and write about Jesuit historian Horacio de la Costa to test if Lacaba was suited for copy editing and proofreading duties.

He had good mentors. Apart from Joaquin, Polotan, Nolledo and

Brillantes who showed through his editing how a story was shaped or a subject handled, there was Teodoro M. Locsin. Lacaba recalled, “What

Locsin did was to comment on or critique some of my articles after publication. But his comments, especially on legal points, were of great help in the writing of subsequent articles.”

He admired the non-fiction of Norman Mailer, Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion. He said they were doing neither “straight news reporting or straight feature writing but using their background in literature.”

At that time, he said, he was more interested in literature than journalism, “There was no journalism at the Ateneo. Their use of literary techniques in characterization and dialogue attracted me,” he related.

Besides reportage, Lacaba has written editorials, poetry, fiction, translations, scripts. Some works put his life in danger.

The University of the Philippines College of Mass Communication named him Gawad Plaridel awardee for print journalism for placing “his considerable writing and communication skills… in the service of the Filipino struggle for social transformation, independence, and progress during the turbulent 1960s and 1970s.”

In his lecture at the award ceremonies, he corrected the announcement lauding him for raising “the bar of excellence for literary journalism to a level unprecedented in the history of Philippine contemporary journalism.” He said his Free Press elders set the precedent in literary journalism, today called creative non-fiction.

Reiterating the journalist’s role of safeguarding freedom of the press, he quoted from the Concerned Artists of the Philippines declaration of principles drawn up before EDSA I.

He said the word “journalists” was interchangeable with “artists” in the declaration: “We hold that artists are citizens and must concern themselves not only with their art but also with the issues and problems confronting the country today. We stand for freedom of expression and oppose all acts tending to abridge or suppress that freedom. We affirm that Filipino artists, in the exercise of freedom of expression, have the responsibility to do so without prejudice to truth, justice, and the interests of the Filipino people.”

A political prisoner for two years, he saw how journalists who spoke and wrote the truth were thrown in jail without charges and the print and broadcast outlets shut down.

A political prisoner for two years, he saw how journalists who spoke and wrote the truth were thrown in jail without charges and the print and broadcast outlets shut down.

He said “developmental journalism” was a concept pushed at the time of the New Society that was propped up by the military.

He described how “developmental” became “envelopmental,” the practice of stuffing envelopes with money to bribe journalists. He noted the rise of hao shiao journalists or impostors, who openly demanded anda or ang datung (pay-off money), and double-faced practitioners who practiced ACDC (acronym for “attack and collect, defend and collect”).

Lacaba said truth-telling, even if it hurts the ears of a few, is the journalist’s duty to help create a foundation for a strong nation.

During the Gawad program, the UP Concert Chorus sang Lacaba’s salinawit or free translation of “Hallelujah” and “You and I.”

Salinawit began as a hobby while hanging around at piano bars after work, doing a Buwan ng Wika exercise and being a dutiful watcher when his mother was hospitalized. When his mom died, he had 30 songs and thought he’d stop there.

Brother Billy chided him, “Why stop at 30? Sounds like ‘Journalist writes 30.'” Lacaba continues freely translating standard and pop songs. He has 134 in his list as of 2012. He can’t have them published because of questions of intellectual property rights. Young crooner Vince Camua took a year to get permission from the estate of the original composer and lyricist to record Lacaba’s salinawit of “That’s All” (“Yun Lang”).

His salinawit and translations of English poems into Filipino are his way of practicing poetry. The translation process enables him to study images, how these are formed in the original language and to attempt reproducing the rhythm in Filipino.

He shifted to writing poems exclusively in Filipino in1970. His college professors Bienvenido Lumbera and Rolando Tinio were writing in the national language. This encouraged him to do the same. His decision was partly influenced by the strong nationalism in those years.

Lacaba remains a busy journalist (writing, editing, fact-checking and proofreading), screenwriter and translator to even think of relaxing or retiring. Like any journalist worthy of his integrity, he has bills to pay.

He’ll eventually find time to read Tikoy Aguiluz’s script for a biopic about his salvaged brother Emman. There is his own script, Balangiga, that won first prize in a historical scriptwriting contest and still awaiting a producer.