From the presentation of Supreme Court Justice Francis Jardeleza in 2014, then the Solicitor General

President Rodrigo Roa Duterte is correct when he questioned recently whether China can actually claim a huge swath of the ocean – by which he meant the Chinese Nine Dash Line Claim over practically the entire South China Sea (including portions we refer to as the West Philippine Sea).

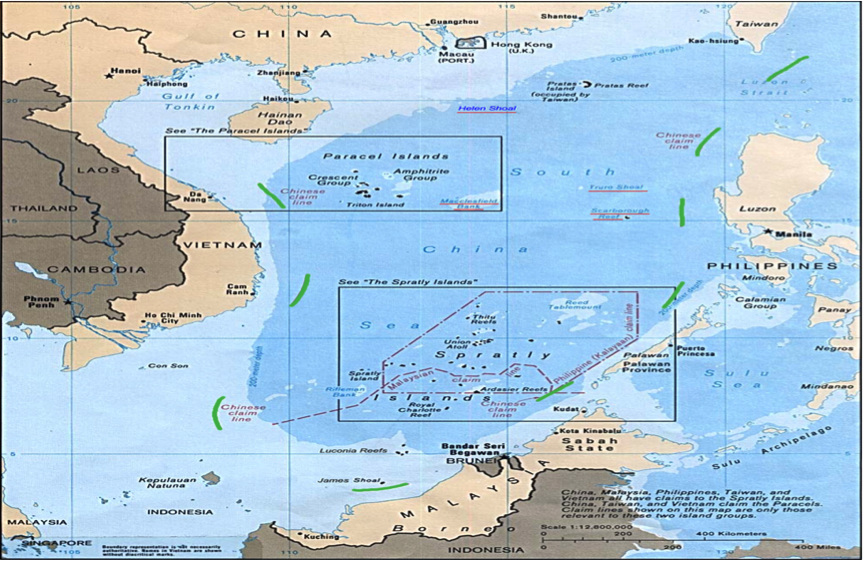

To begin with, the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in our arbitral case against China, has already ruledin 2016 that the Chinese claim does not and cannot amount to a claim of title (or ownership) of such a wide expanse of waters; moreover, being in the nature of an historic claim, it is deemed to have been waived by China when it became a party to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

But in his usual rambling way, at the same time President Duterte said Chinese actions in our Exclusive Economic Zone are not an “attack” on our sovereignty, as sovereignty only extends to the Territorial Sea.

Unless the President meant an “armed attack” under international law – in which case he is correct that it is not – his statement tends to fuel more misunderstandings of the maritime entitlements accorded by the UNCLOS to coastal states like the Philippines.

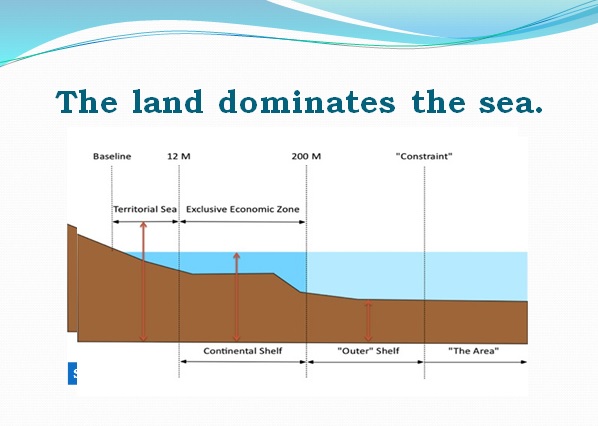

The UNCLOS provides that coastal States have sovereign rights to a Contiguous Zone (CZ), a Continental Shelf (CS), and an EEZ, to be measured from the baseline of its territory. Sovereign rights pertain to a state’s exclusive rights, to the exclusion of other states, to the economic use and conservation of marine resources.

The Contiguous Zone covers that part of the sea extending for 12 nautical miles from the limits of the Territorial Sea (TS), or 24 nautical miles from the baseline. Within this zone, a state may exercise certain protective jurisdiction, such as customs enforcement, fiscal, immigration and sanitary rules.

Meanwhile, the EEZ is an area adjacent to the Territorial Sea covering up to 200 nautical miles from the same baselines from which the territorial sea is also measured. Within the EEZ, a state has exclusive rights to explore, exploit, conserve and manage natural resources, as well as build artificial islands, carry out environmental protection and conduct marine scientific research.

The CS is that natural prolongation of the landmass of a State under the sea extending beyond the Territorial Sea up to 200 nautical miles from the baselines of the territorial sea.It is coterminous with the EEZ, although may extend for another 150 nautical miles under the Extended Continental Shelf (ECS) Regime, depending on the presence of certain geological features.

Its CZ, CS, EEZ and ECS are no less part and parcel of the country’s entitlements as a sovereign state as its TS is. Moreover, under the 1987 Charter, all of these maritime entitlements are considered part of our National Territory, even if under international law, different modalities of sovereign entitlements apply to the maritime regimes beyond the TS.

In our arbitral case, Recto Bank has been declared part of the Philippine EEZ, and is thus coextensive with its continental shelf. No other country may fish, or conduct oil and gas explorations there – or other economic activities – without the consent of the Philippines.

The Chinese claim cannot coexist with our sovereign rights over the Reed Bank. In fact, international law has already declared the Chinese claim to be a violation of China’s obligations under the UNCLOS. Thus, continued Chinese incursions into maritime areas declared part of the Philippine EEZ are a diminution of our sovereignty as a state, and an existential threat to the international rule of law.

We should vigorously protest each incursion, and use every legal means available to us, to deny a regional bully what it illegally wants. And as Indonesia and Vietnam have shown, we don’t need to go to war with China to protect our sovereign rights.

(The author, an alumnus of the University of the Philippines College of Law, lectures in international law at the Lyceum Philippines University College of Law. He is also an officer of the Philippine Society of International Law (PSIL). The opinion expressed in this essay is entirely his and does not reflect the official views of the aforementioned organizations.)