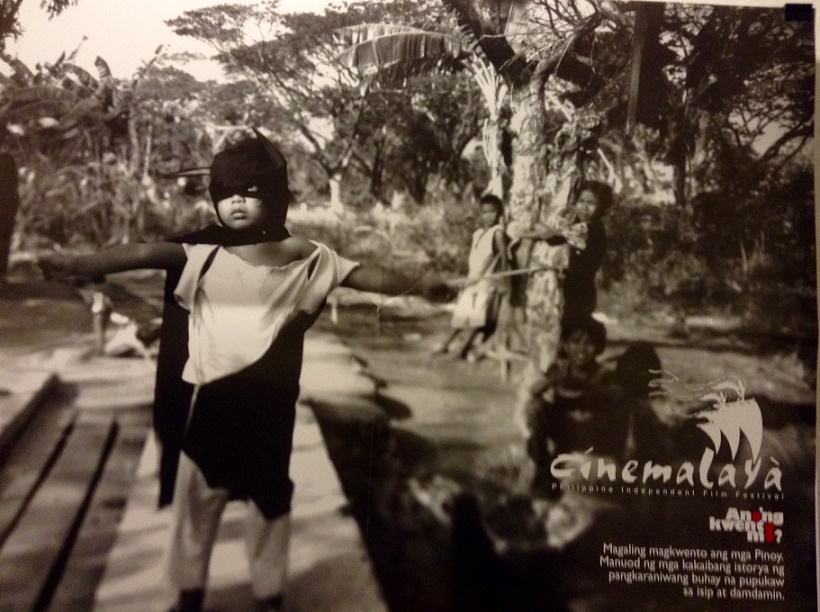

Cinemalaya

Posters: everywhere, short-lived, and thrown away. Such is the fate of most posters but not at the Cultural Center of the Philippines with Poster/ity: 50 Years of Art & Culture at the CCP that runs through 26 May 2019, with free admission. It features over 200 selected posters of exhibitions, performances, and other events held at the CCP from 1969 to the present, as part of its 50th anniversary celebration this year.

Information in a poster is made of textual and graphical elements. At one glance, you know who, what, when, where, and how much. As a study of Philippine modern graphic design, the CCP posters also reflect changes in society and politics as well as in new media and technology

From Squeegee to Photoshop

Entering the main gallery, one is greeted with a silkscreen set-up provided by a design studio. Screen printing is a common technique used in poster production as well as in the designs of t-shirts that Filipinos love to wear.

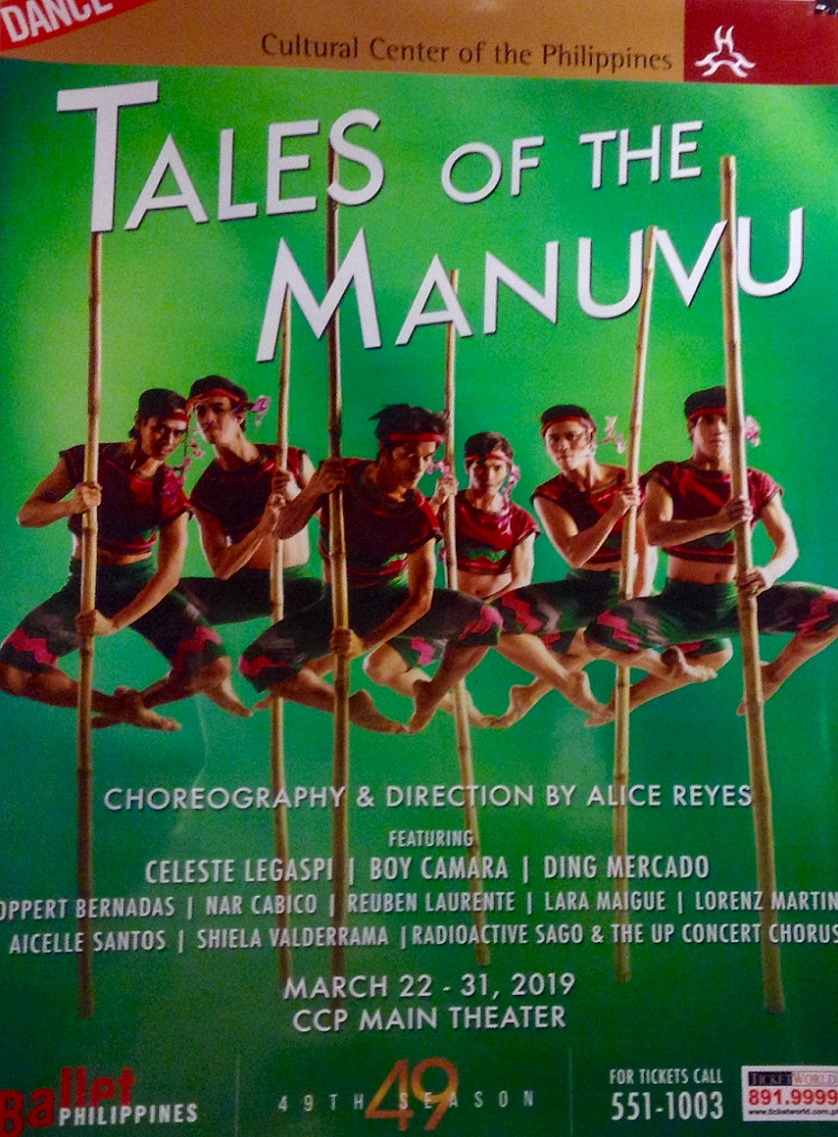

Manuvu

The deconstruction of a poster is shown in terms of composition, image, text, and printing process. It explains printing methods such as offset lithography, screen printing, and collage, both analog and digital. Screen printing or serigraphy is a variety of stencil painting that uses a screen (made of silk or synthetics) stretched tightly over a frame. Then, ink or paint is forced through with a rubber blade or a squeegee, onto the paper.

Chabet and Albano

Roberto Chabet (1937-2013) and Raymundo Albano (1947-1985) directed the production of many early CCP posters. Both artists, Chabet was the CCP’s founding museum director and its curator; Ray Albano succeeded him as head of the Museum and Art Gallery from 1970 to 1985.

Many artists and designers have produced posters for the CCP, including B+C Design, Girl Friday Design, Cesar Hernando, Fernando Modesto, Nonon Padilla, Ige Ramos, and Leo Rialp. On the other hand, exhibiting artists, resident and guest companies usually designed or produced their own posters that CCP would circulate. However, many creators of CCP posters have remained unidentified, as it is not a practice for posters to be signed. Maybe, it is time to end this practice and give credit to poster creators.

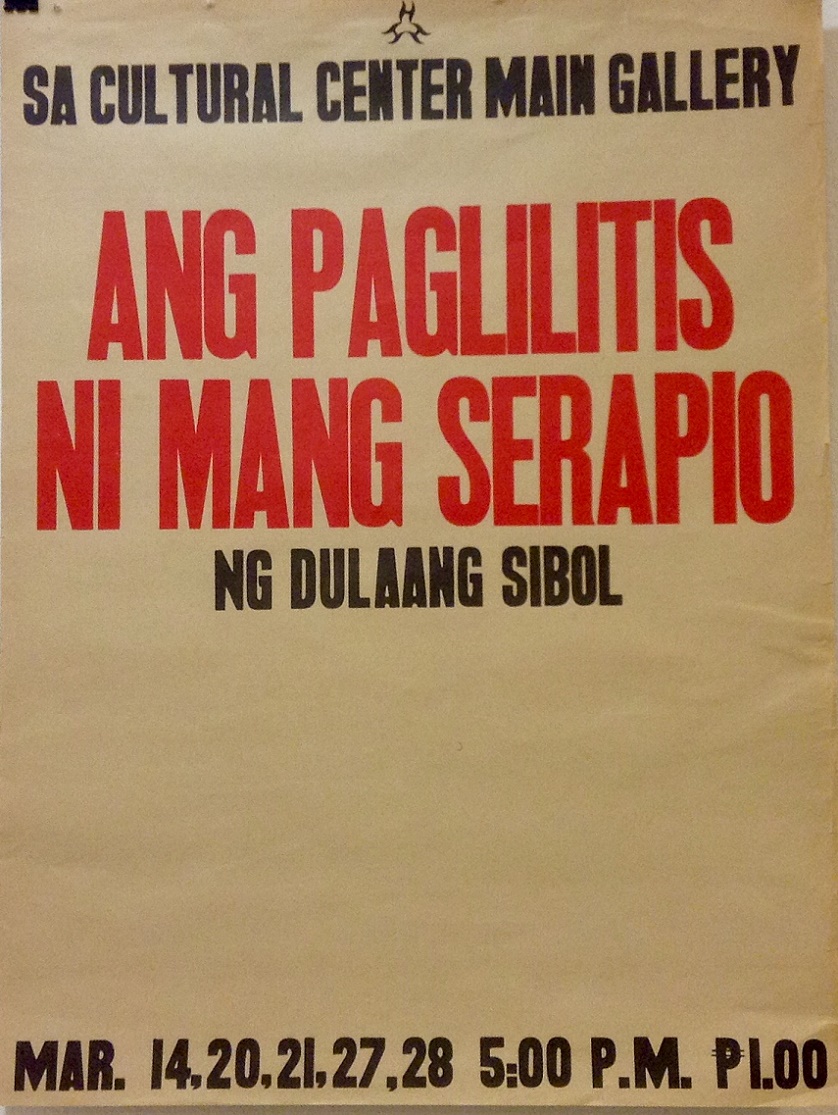

Mang Serapio

Filipino Artistry, Bravo!

Art, design, and advertising rolled into one, each poster marks the best of Filipino art and culture, as embodied in the production of a play, a musical, a performance, or an exhibition. As visual history, the CCP posters document the artistic and cultural achievements of a nation. Some key posters that benchmark the country’s cultural history:

- Ang Paglilitis ni Mang Serapio: a 1968 play by Paul Dumol who wrote it when he was a high school student in Ateneo. It remains as one of the most produced one-act play in the country. The CCP has presented thousands of theater productions, from sinakulos to zarzuelas, to Shakespeare, and original works in Filipino by Filipinos.

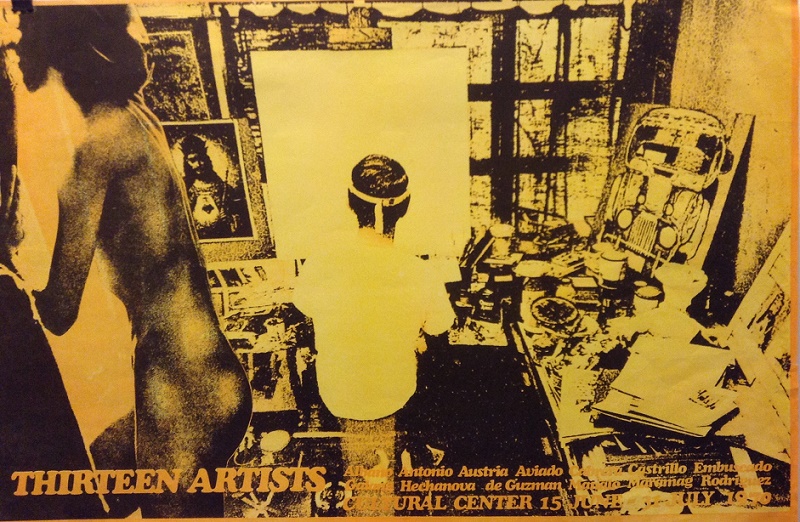

- Thirteen Artists: initiated by Chabet in 1970 and one of the first programs in visual art to recognize emerging Filipino visual artists, it is a triennial award today.

- Cinemalaya: an annual independent film festival since 2005, to encourage new works by Filipino filmmakers.

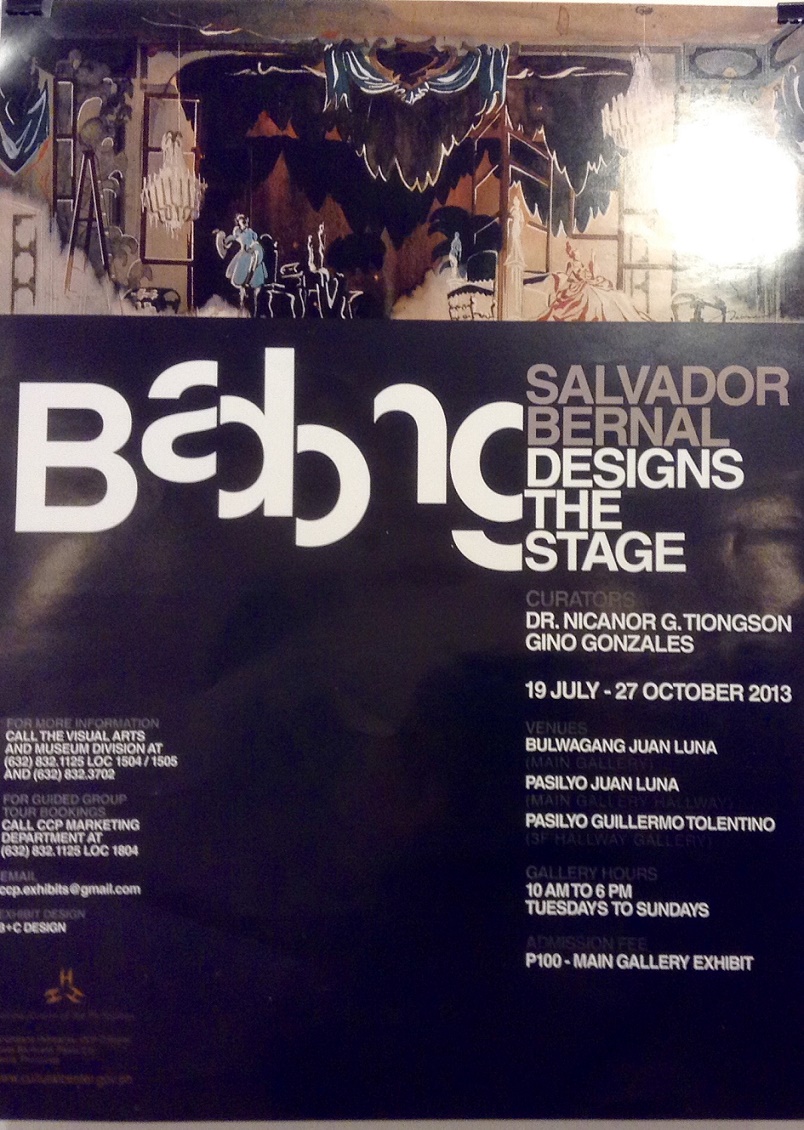

- Badong: Salvador Bernal Designs the Stage: Salvador F. Bernal, (National Artist for Theater Design, 2003) had designed more than 300 productions for drama, musicals, concerts, and operas and introduced Philippine theater design to the world.

- Tales of the Manuvu: first produced in 1977, this rock opera ballet is choreographed by National Artist for Dance and the artistic director of Ballet Philippines, Alice Reyes. It tells the creation story of the Manobo tribe of Mindanao. National Artist for Literature Bienvenido Lumbera wrote the libretto. In 1977, Boy Camara’s band, the Afterbirth, performed live music; in 2019, Radioactive Sago Project provided the music.

Thirteen artists

Then and Now

For many people, the CCP is synonymous with former First Lady Imelda Marcos, and she gets proper recognition in the exhibition, as the one who envisioned the center as the first national theater in the country. It was designed by National Artist Leandro Locsin and opened on September 8, 1969.

Under the Marcos regime’s “New Society,” Imelda Marcos trumpeted “the good, the true, the beautiful.” The posters in 1970s reflect the regime’s hunger for international recognition. Prominent international artists graced the center: conductor Helen Quach, India’s sitar virtuoso Ravi Shankar, Dame Margot Fonteyn with Ivan Nagy, the Bolshoi Ballet, or the pianist Van Cliburn who was closely associated with Imelda Marcos during the martial law years.

But times and politics change: after the EDSA People Power in 1986, the CCP embarked on a “more nationalistic search for a new Filipino identity”; today, the CCP celebrates “the diversity in Filipino cultural traditions and histories.”

Salvador Bernal